I've collected stuff over the course of my life: Coins, stamps, sports cards, old maps, you name it. But always at some point I start to sniff the obsession, and then I go out and sell it all off.

What I've got right now is a stack of old postcards. I was the first of my family in my generation to buy a house. That, and my known interest in historical stuff, prompted my parents to dump all the family white elephants on me. Stuff not worth anything or useful to anyone, but too much a part of the family to simply pitch in a Dumpster or set up on folding tables at a yard sale.

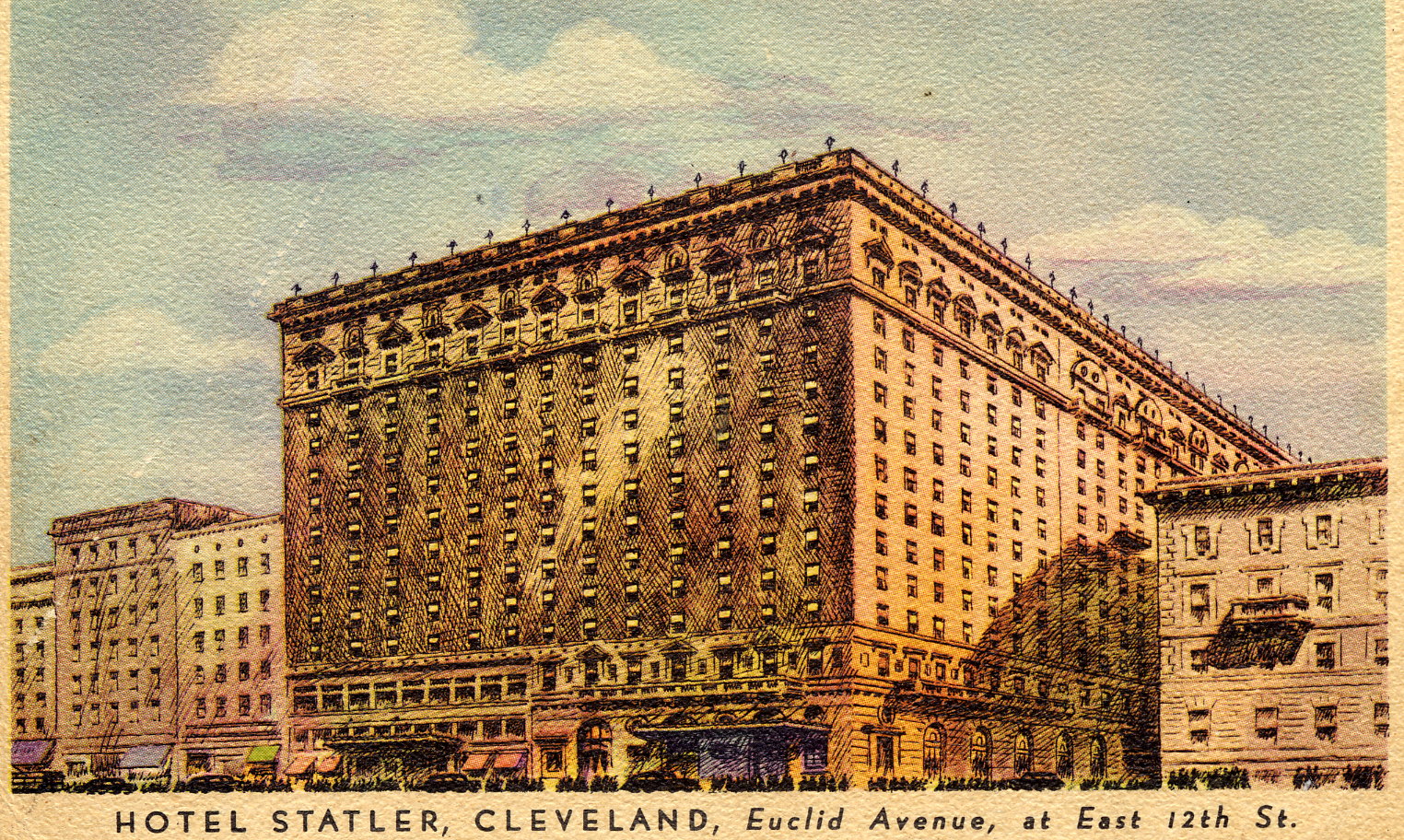

Among the elephants were several albums full of old postcards. Some of them were fascinating. In the "why on earth would anyone make a postcard of this?" way. Not only did someone make it, my family bought it, or got it in the mail, and then hung on to it for 80 years. Like this one:

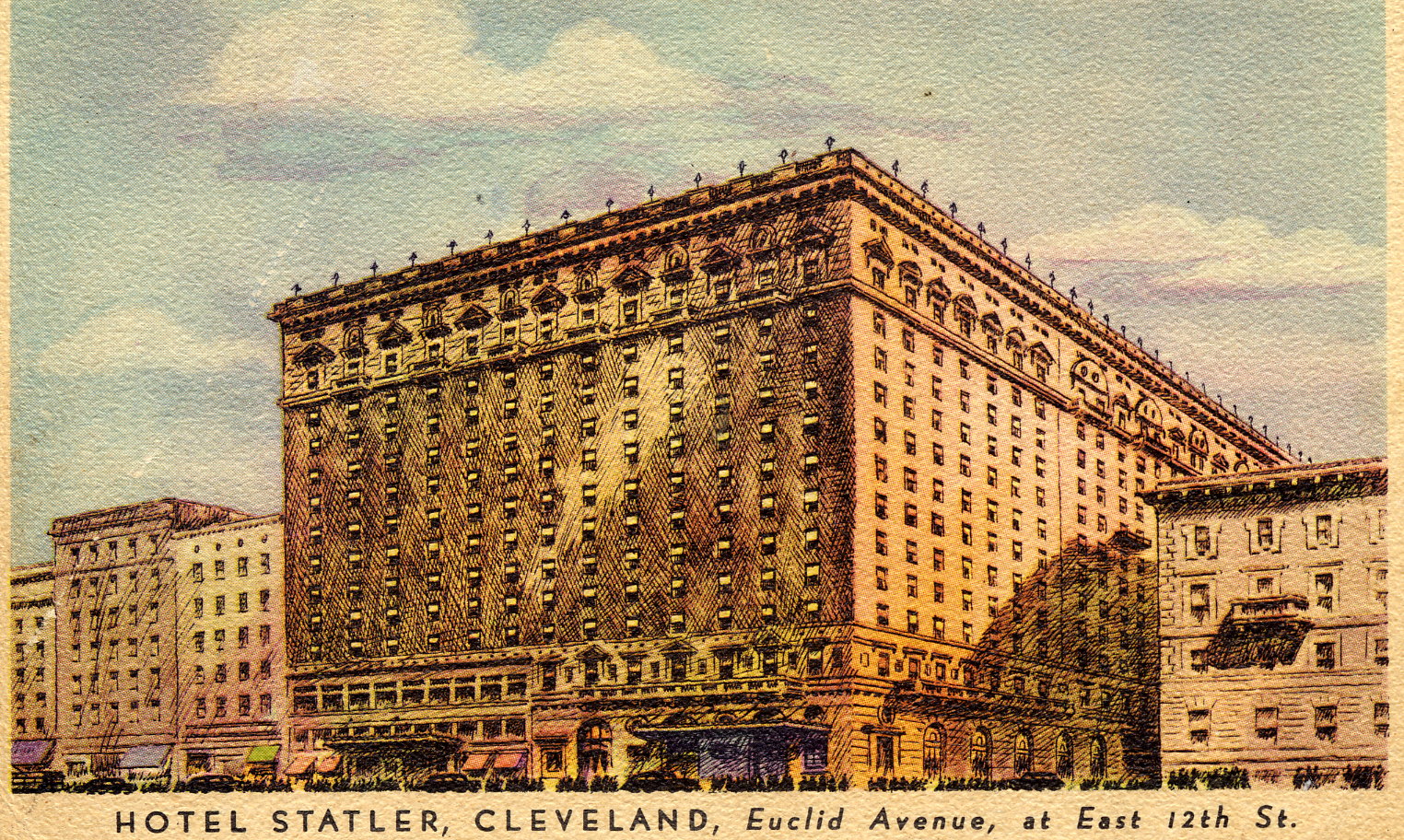

It seems it's still there, converted to luxury apartments. But that's the kind of thing I almost don't want to know. I want to hold on to this picture, this day in 1929 or whenever, and wonder why my grandmother and her new husband ever moved, briefly, to Cleveland. Why they bought this but never sent it to anyone. Why they kept it.

My favorite postcards are representations of the kind of places I imagine most people want to forget when they travel. Train stations, municipal buildings, grim and spiritless hotels. Like this one:

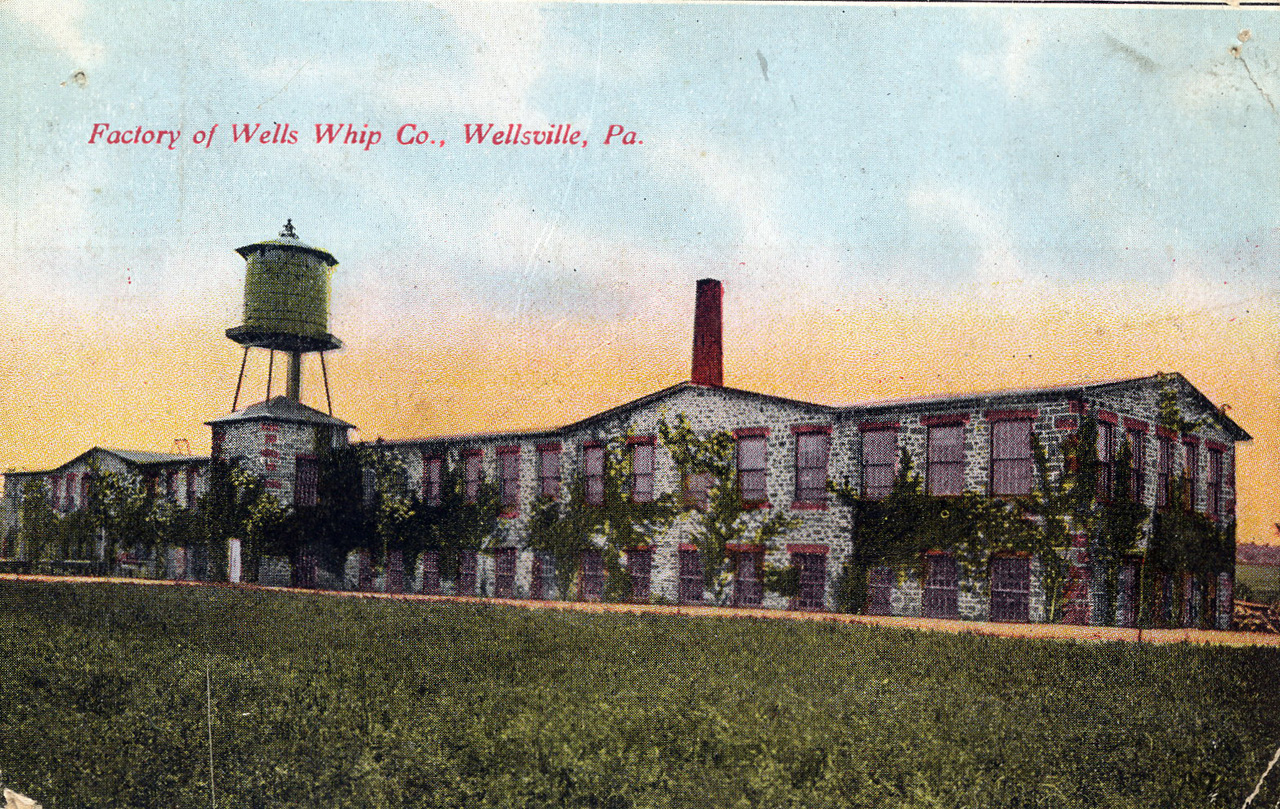

People would make a postcard out of just about anything.

"Factory of Wells Whip Co., Wellsville, Pa." And what a cheerful bit of architectural eye candy it is.

To be fair, though, this appears to be a business postcard. On the back, in the space for message, is pre-printed, "On or about _____, C.M.S. Gruber will call on you with a complete line of Whips and Flynets of every description." Either a business postcard or BDSM fetish tease.

The funny thing is, in the blank for a date is hand-written "soon." Some business! The company's motto is "Wells Whips Wear Well," which is such a tongue-twister it encourages the theory that this card is somehow meant to be sadistic.

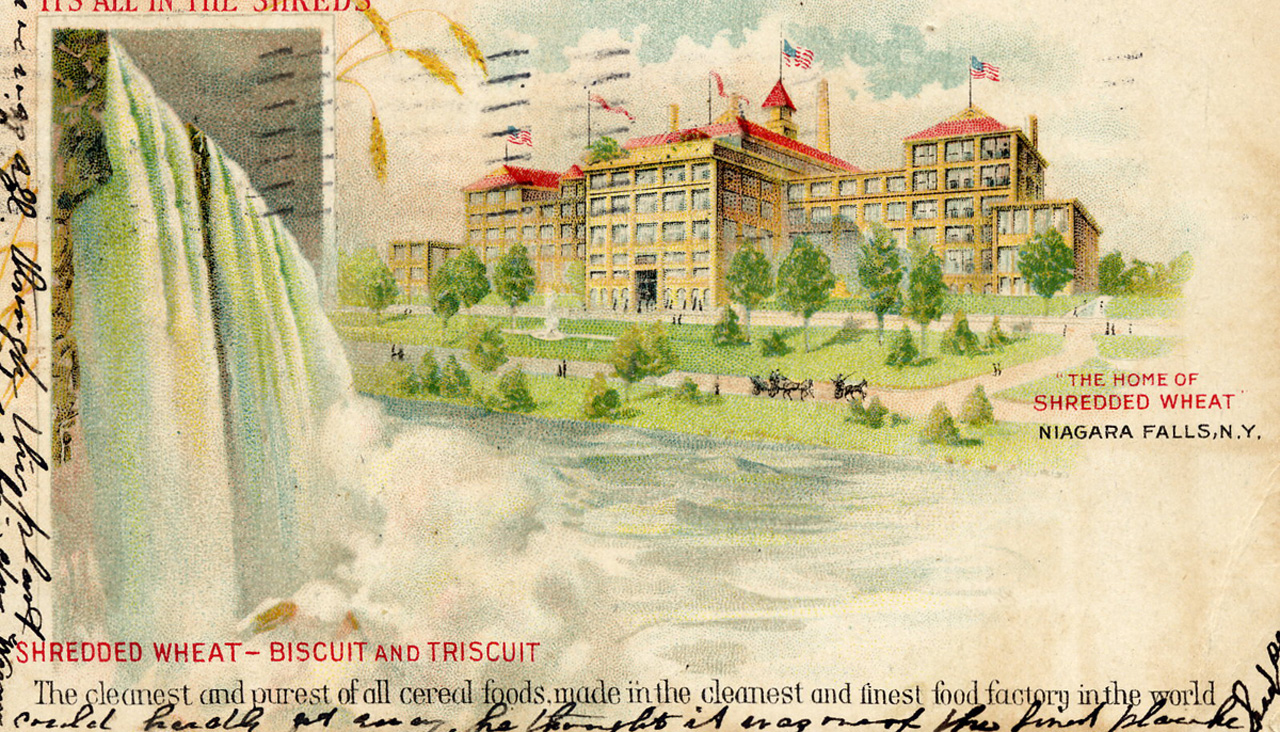

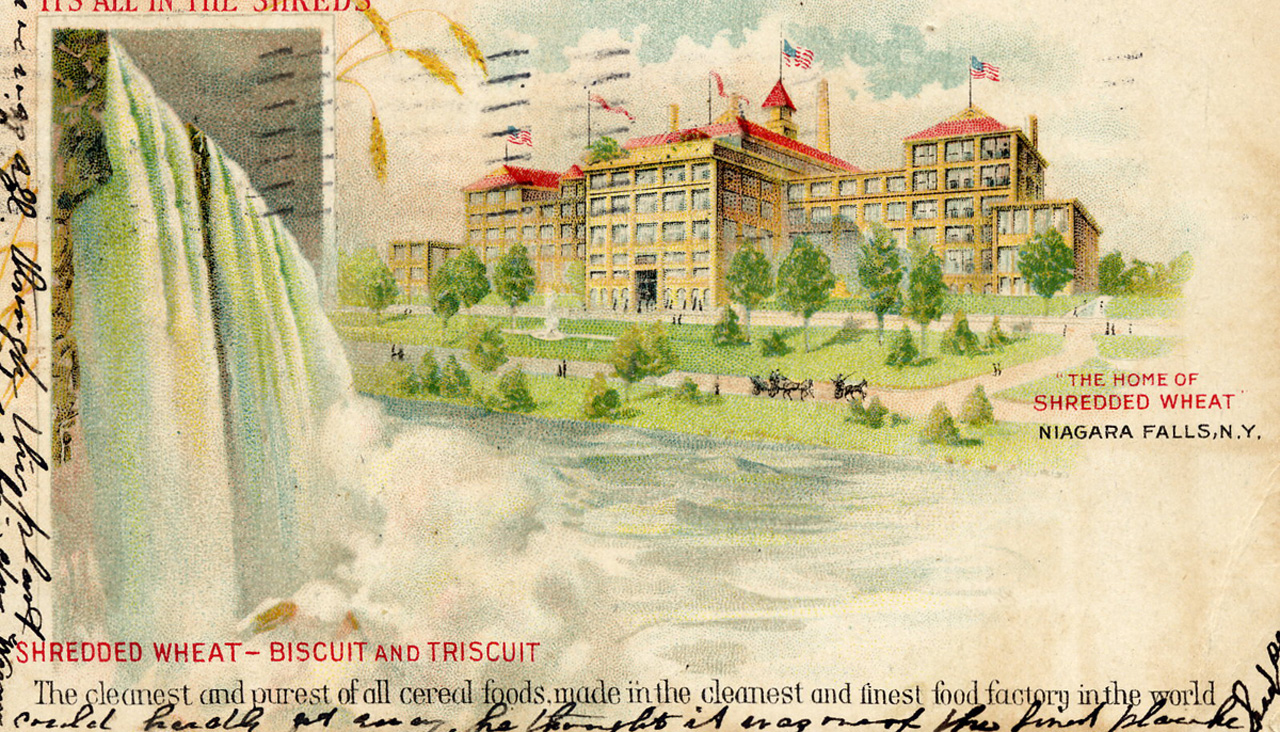

Did you know Shredded Wheat had a home? Did you know it was bigger than your home. True! And here is "The Home of Shredded Wheat, Niagara Falls, N.Y."

Their motto is (or was) "It's all in the Shreds," which says it all while saying nothing at all. Unlike the whip card, this wasn't a business calling card. Someone actually mailed this to my great-great-grandmother. The writing seems to be a description of touring the plant. But the thing is postmarked "Colorado Springs." Go figure.

I didn't add at once to the family albums. But I started dating a girl who collected antique jewelry. She'd haunt the antique malls and flea markets, looking for the perfect find. Rather than follow her like Mary's little lamb from stall to stall, I started flipping through the postcard bins. I decided if I never spent more than 10 cents on any one postcard, and avoided knowing anything about them, it wasn't really collecting.

I don't specialize in anything except the blandly bizarre. I tend to like the old Atlantic City hotels, but it's not enough of a concentration to amount to a specialty. I couldn't tell you the history of the various printers, or the hallmarks of collectibility. And I love it like that. They show me what they choose to show and I accept it. What they mean to me is between me and them, and no Guide to Collectible Postcards comes between us.

Here's the old Hotel Chalfonte in Atlantic City. I'm pretty sure this is where my grandparents stayed when they took summer trips down the Shore in the teens: It had Philadelphia Quaker owners dating back to 1868 and must have been a predictable and placid hotel by the time they established a base there. I've got an old book of matches from the place that I found in my grandfather's cigarette box decades after he died of heart disease.

When gambling came in, the new money tore down the Chalfonte to make a parking lot for the Resorts casino it opened inside the shell of the bigger hotel next door, the former Haddon Hall. Here you can see what the scene looked like when the behemoth and glamorous Haddon replaced the older wooden version (which you can see a bit of in my postcard) in 1929.

This, on the other hand, decidedly was not the kind of hotel where my grandparents would have stayed. Just look at that typeface, and the woman is scandalously dressed. No doubt a haunt of rich bootleggers. And the dropped apostrophe of "nations capitol" is not to be lightly forgiven by a family of schoolteachers.

Sure enough, the inscription on the back reveals it was sent from one of the neighborhood girls to my two great-aunts back home.

"250 rooms," 200 of them with bath! Modern! Fireproof! Which just reminds you that fire safety used to be one of the chief concerns of people booking hotels.

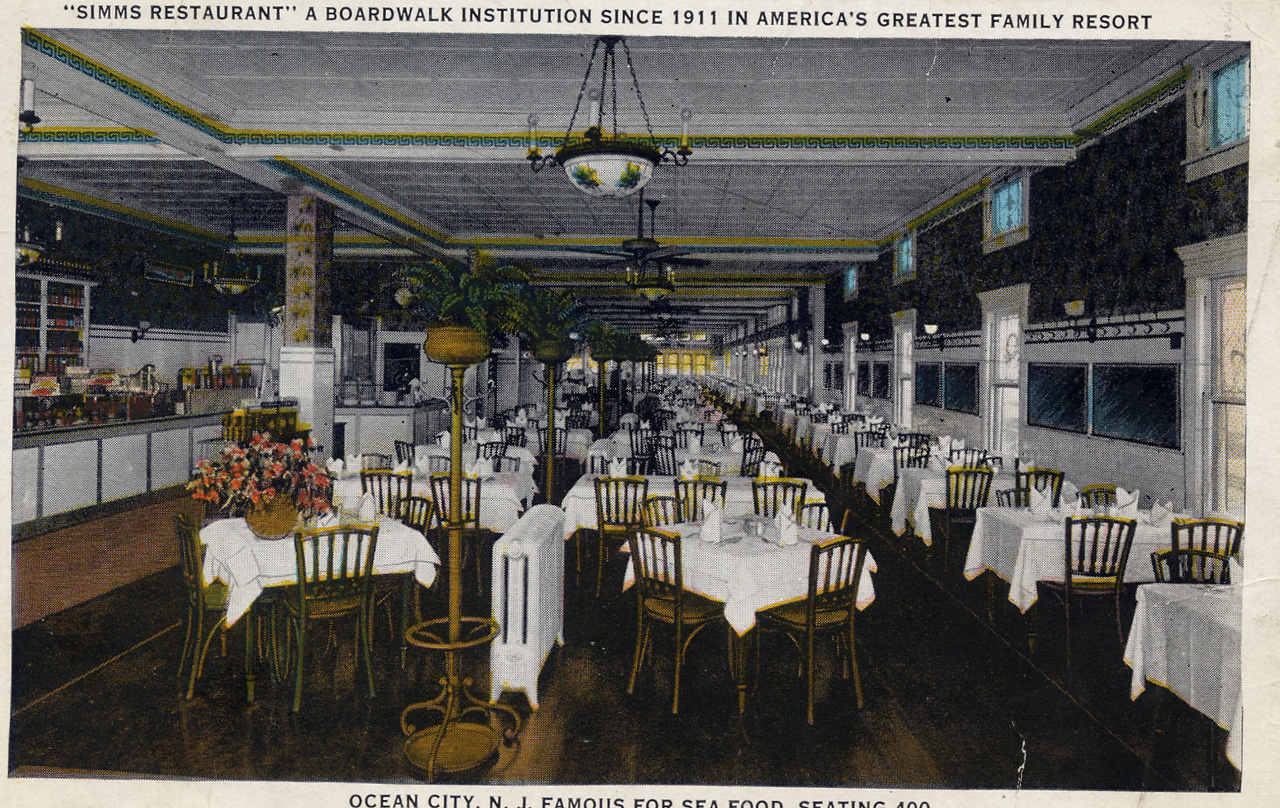

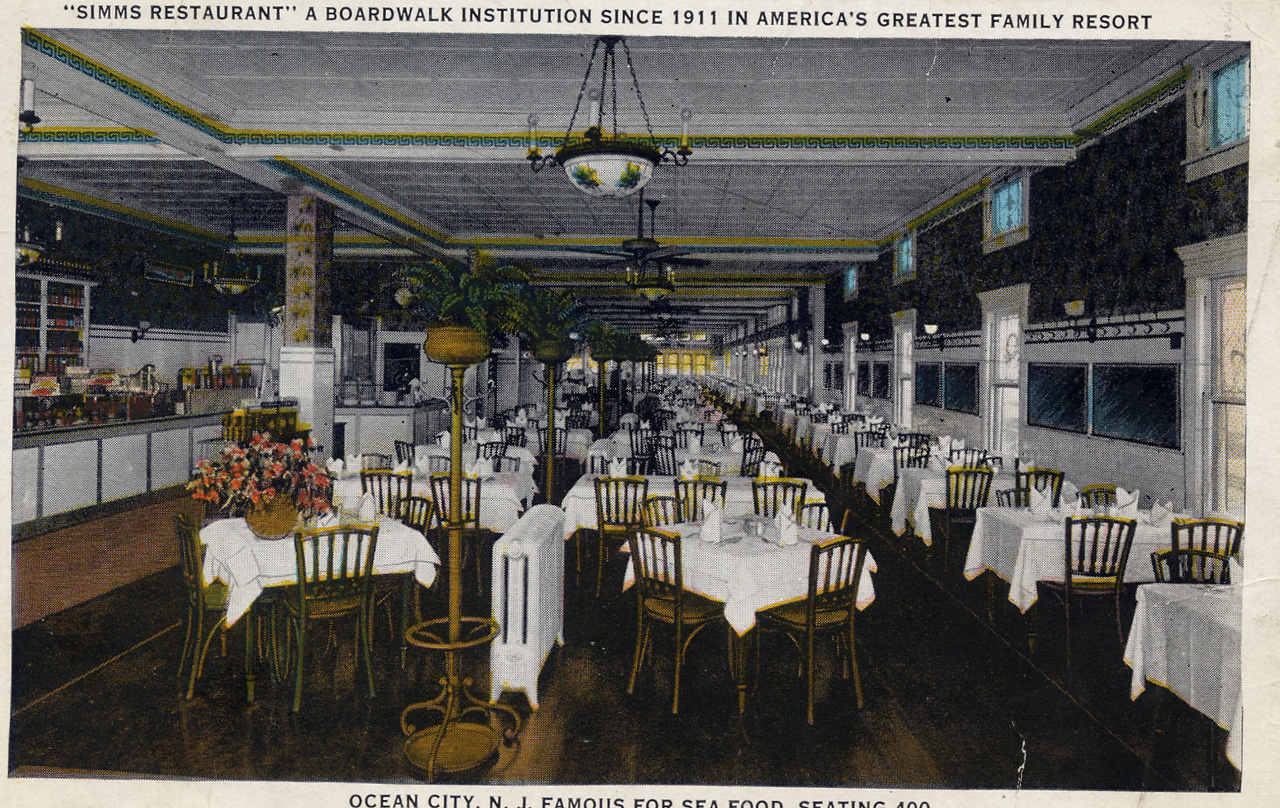

Simms Restaurant

Back when dining out was not considered to be a private experience for most people. Coatracks, hard chairs, small tables, and radiators spread around in a big open space.

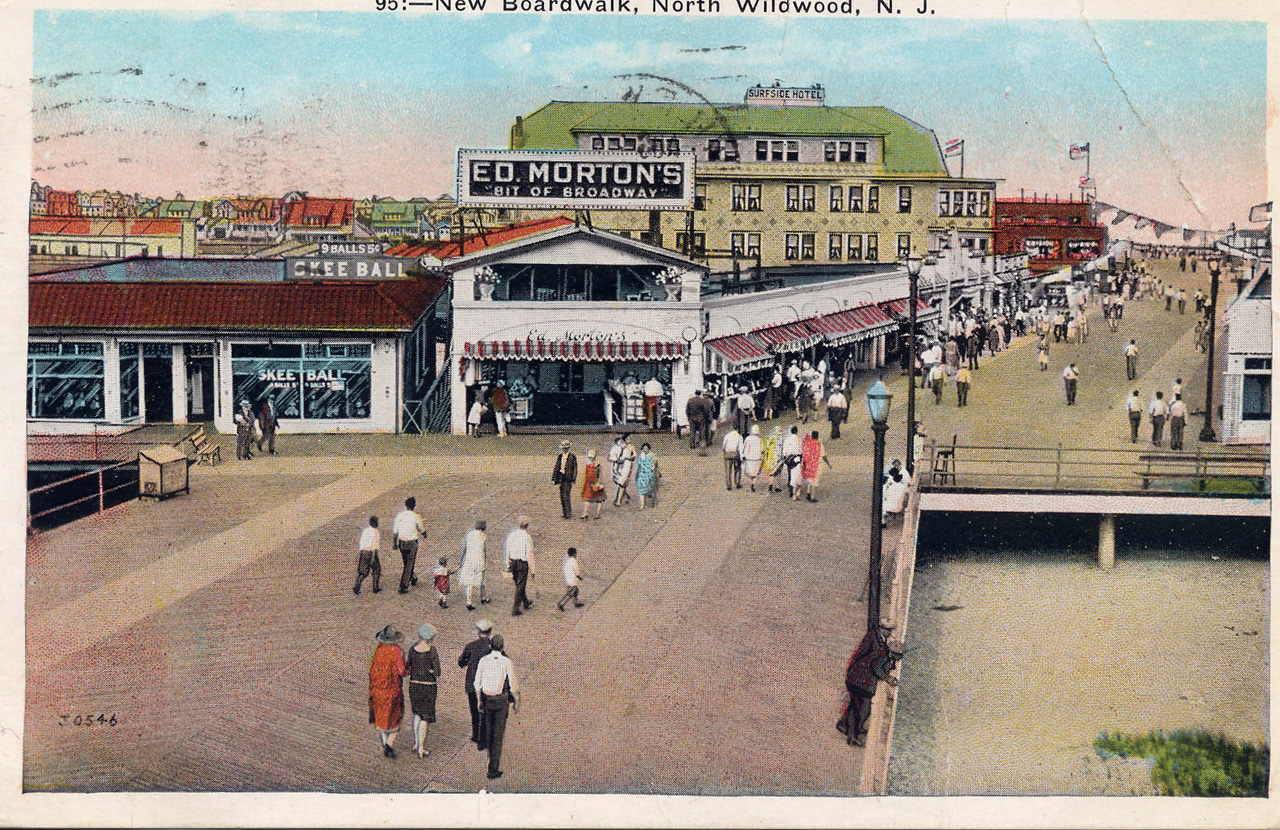

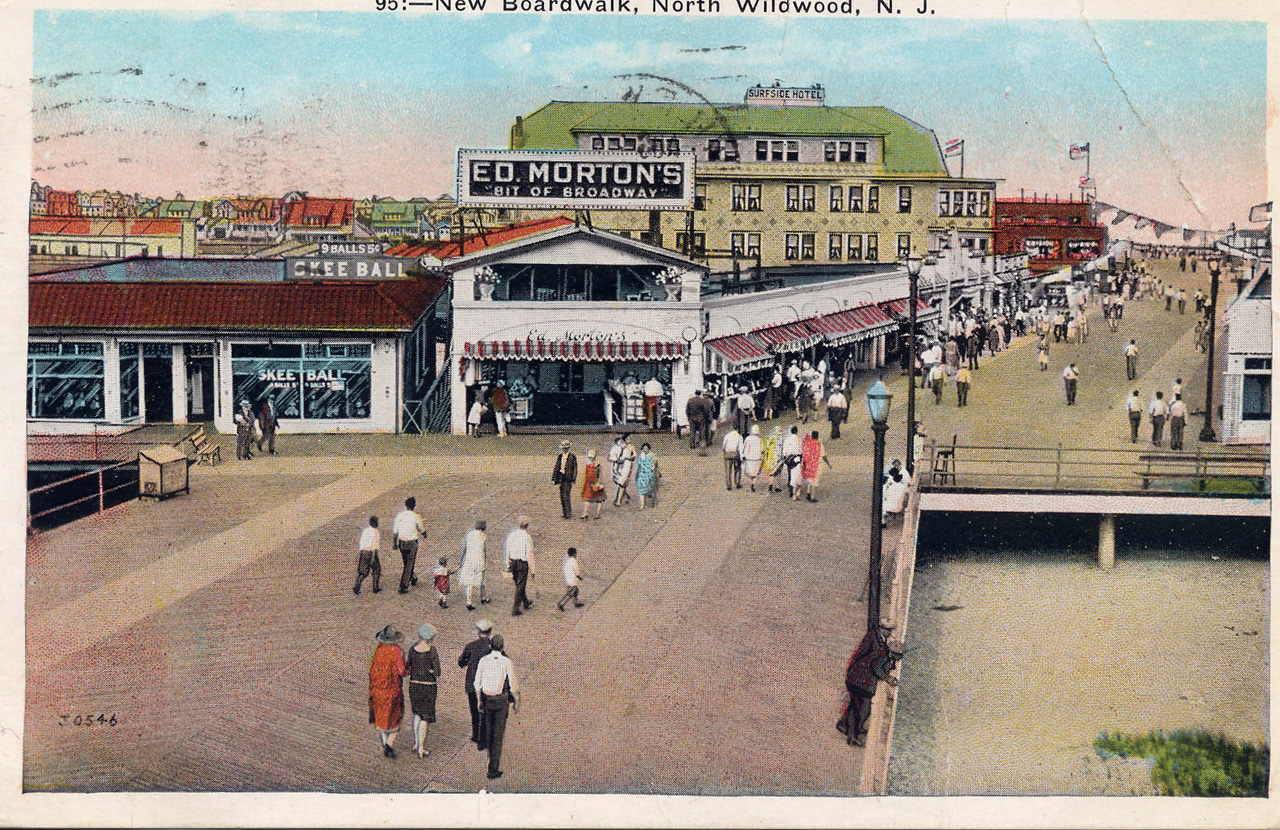

Here are two views of the Jersey Shore, circa 1930. The first is North Wildwood:

It prominently features Ed Morton's Bit of Broadway, a popular restaurant run by a retired Vaudeville star who had been known as the "Singing Cop;" and it shows how far Skee Ball, sport of kings, had migrated in 20 years from its birthplace in Philadelphia.

And this is Ocean City:

The old Moorlyn Theater visible in the background survives, sort of. But Shriver's Salt Water Taffy is still going strong, much to the fiscal benefit of the dentists who have to replace the fillings it pulls right out of your teeth.

What amuses me about this pairing, though, is that nowadays, Ocean City is "America's Family Fun Place," a dry town suitable for young children and old people (and with a zoning board's nightmare of liquor stores and dance clubs stacked up on the traffic circle just outside the city line). While Wildwood is where the teenagers go after graduation to take their first plunge into sin.

But in these pictures the order seems reversed. North Wildwood (which admittedly is not quite Wildwood) features old people and families with young kids. While Ocean City features flappers and loafers who look like extras from a gangster film, that trio of bad-girl Clara Bow wanna-bes over on the left corner, and that disreputable fellow with the unmarked parcel on the right.

A couple of New York City hotels; the Manger:

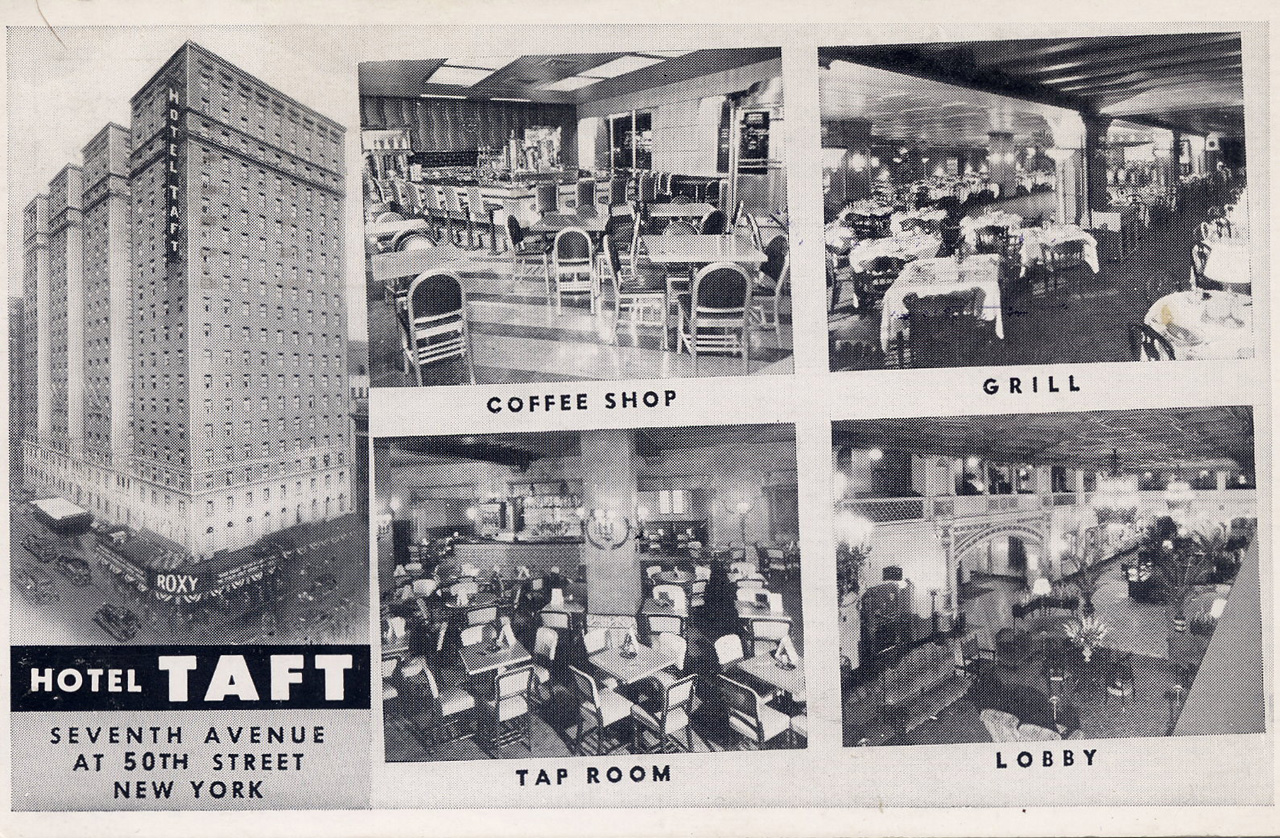

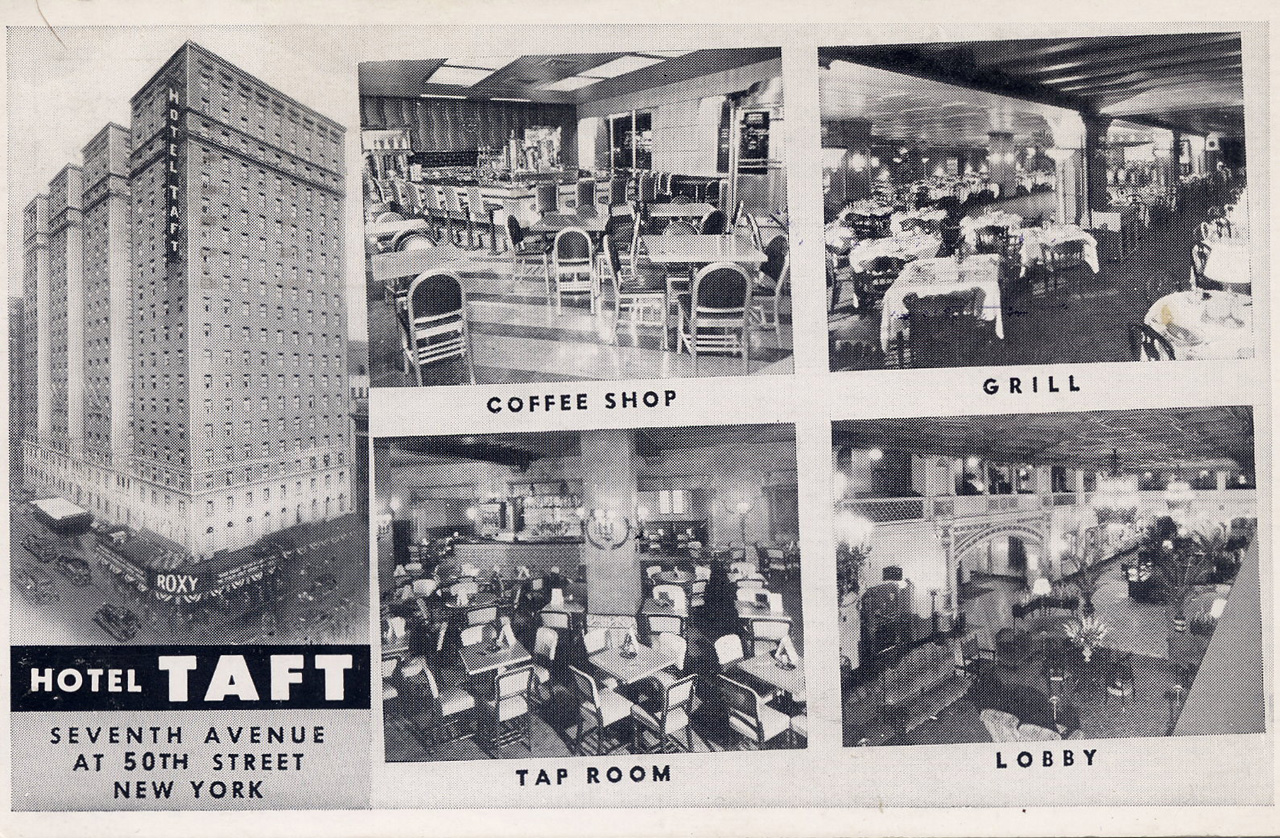

... and the Taft:

It wasn't till I was scanning them in that I noticed they're the same building. Sure enough, the address is identical.

Here's an interesting short history of the place

The massive building on the east side of 7th Avenue between 50th and 51st turns 80 next year, but don't expect any birthday celebrations. For most New Yorkers, the boxy Spanish Renaissance structure barely registers, lost amidst sleek newcomers like Lehman Brothers' headquarters a block away. But the Hotel Taft, as this building was once known, has a long history that reflects all the frenzy of 20th-century Manhattan. When it opened as the Manger in November 1926 (on the site of a railway-car barn), it was the third-largest hotel in the city, with 20 stories, 1750 rooms and a special "key chute" on each floor that whisked lost items straight to the lobby desk.

Among other things I learned, Jimmie Rodgers died here, far from his country music roots, in town to make recordings in a desperate bid to raise money to pay off his medical bills. The line, "For much of its history, the Taft was a low-priced and dependable tourist hotel" explains why these postcards got into my family collection. That was their kind of place.

The grill was home base for Vincent Lopez and his dance band.

Among the stars that began their career with Lopez were Artie Shaw, Xavier Cugot, Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey, Glenn Miller and Tony Pastor. Also vocalists Betty and Marion Hutton sang with his orchestra but on one occasion, part-time saxophonist Rudy Vallee was told by Lopez NOT to sing... an order he evaded the minute Lopez left the bandstand.

The hotel still operates under an upscale Italian chain as the Michelangelo, N.Y.

But I think my favorite aspect of the Taft is that tap room. That's what a beer bar should be: A bunch of little tables, big enough to hold three pitchers and about 20 mugs, that you can push together at will to form whatever arrangement you please as the night goes on. Some ashtrays. Chairs. Period.

Looking like a French chateau lifted by alien gravity beams and dropped whimsically atop an insurance company's headquarters, Philadelphia's Bellevue-Stratford Hotel rules over Broad Street in 1904, the year it opened as the most glamorous hotel in the nation.

Two years later it became the home of the Philadelphia Assemblies, an annual social event that was like a debutante ball for grown-ups. According to Nathaniel Burt's Perennial Philadelphians, it is "of all Philadelphia's many institutions the most socially venerable and the most venerated, and combines in a fine bouquet almost everything characteristic of the city. It is both a club and a family occasion,and though a dance, involves food and drink, and a good deal of sitting."

The Assemblies date back to colonial times (though it was not founded by Ben Franklin), and early guests are said to have included an Indian chief who terrified the ladies with a war dance, and his wife, who offered herself sexually to the governor of Pennsylvania in a traditional gesture of hospitality.

Its exclusiveness is legendary, and the rules of who's on the list and who's not seem harsh and dated, but Burt (writing in the 1970s) found they served the purpose.

If a daughter marries out of the Assembly, she stays out. A son however can marry anybody and stay in. "A man can bring his cook, if she's his wife," is the usual way of putting it. He can't bring her if she has been divorced, however, or come himself if he has been. In older days this hard and fast rule was said to have kept many Philadelphia marriages together, but now it just means the continual weeding out of possible subscribers. Archaic as the rule seems to outsiders, in as tight a world as this, most divorced members of the Assembly immediately remarry other divorced members of the Assembly, and if they all got together in the same room it might be deuced awkward.

Needless to say, Mohawk maidens no longer were invited, though by the 20th century some of the debauched and eccentric Philadelphia gentry behaved little better. Nonetheless, in more recent times, as divorces and marriages out of class rose, some civic leaders from even the old families found they had to pull every wire in reach to get a daughter and her escort invited -- only to have them skip out early, finding the event insufferably stuffy. It seems likely (at least to me) the Assemblies are the source of the society slang phrase for "huge fashionable party where everyone knows everyone, characterized principally by socializing," said to have been coined by Averell Harriman's second wife: Philadelphia rat-fuck.

The hotel was well past its prime when it hosted an American Legion convention in the summer of 1976 and hundreds fell mysteriously ill with what subsequently came to be called Legionnaire's Disease. The hotel closed for a while, and it has been remodeled and reopened several times since, as part of various chains, but its glory days are over.

You can't get into the Assemblies, but you can get into the building and marvel at the marble stairs, hand-wrought iron railings, and gilt ceilings. But they sit awkwardly amid the upscale chain shops that now occupy the chopped-up and walled-up space of what used to be the large downstairs public areas. There was still an excellent and cozy bar on the top floor, last time I was there, where you can get nicely smashed in good old debauched Philadelphia style.

The Lorraine Hotel on North Broad Street in Philadelphia. Now boarded up, awaiting a plan from its third owner in six years. My sister lives half a dozen blocks from here; we pass it by a lot. Home of Father Divine's kooky social gospel mission for half a century.

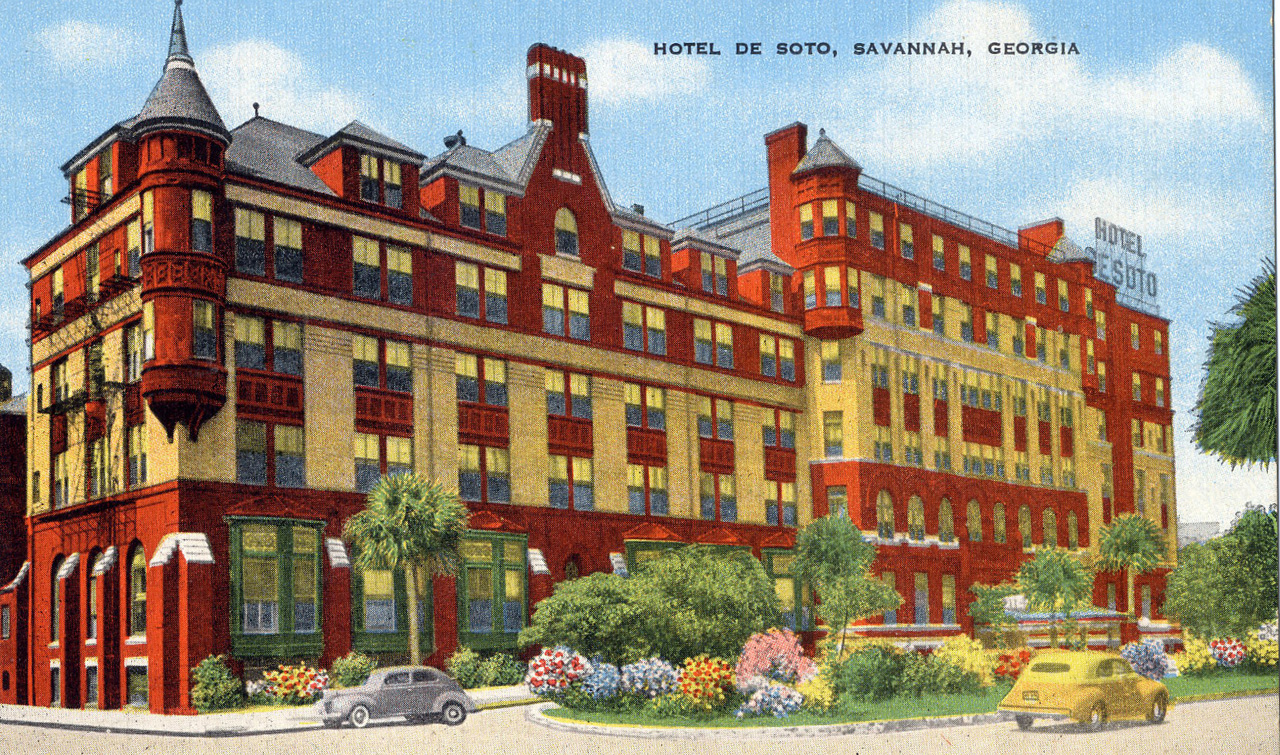

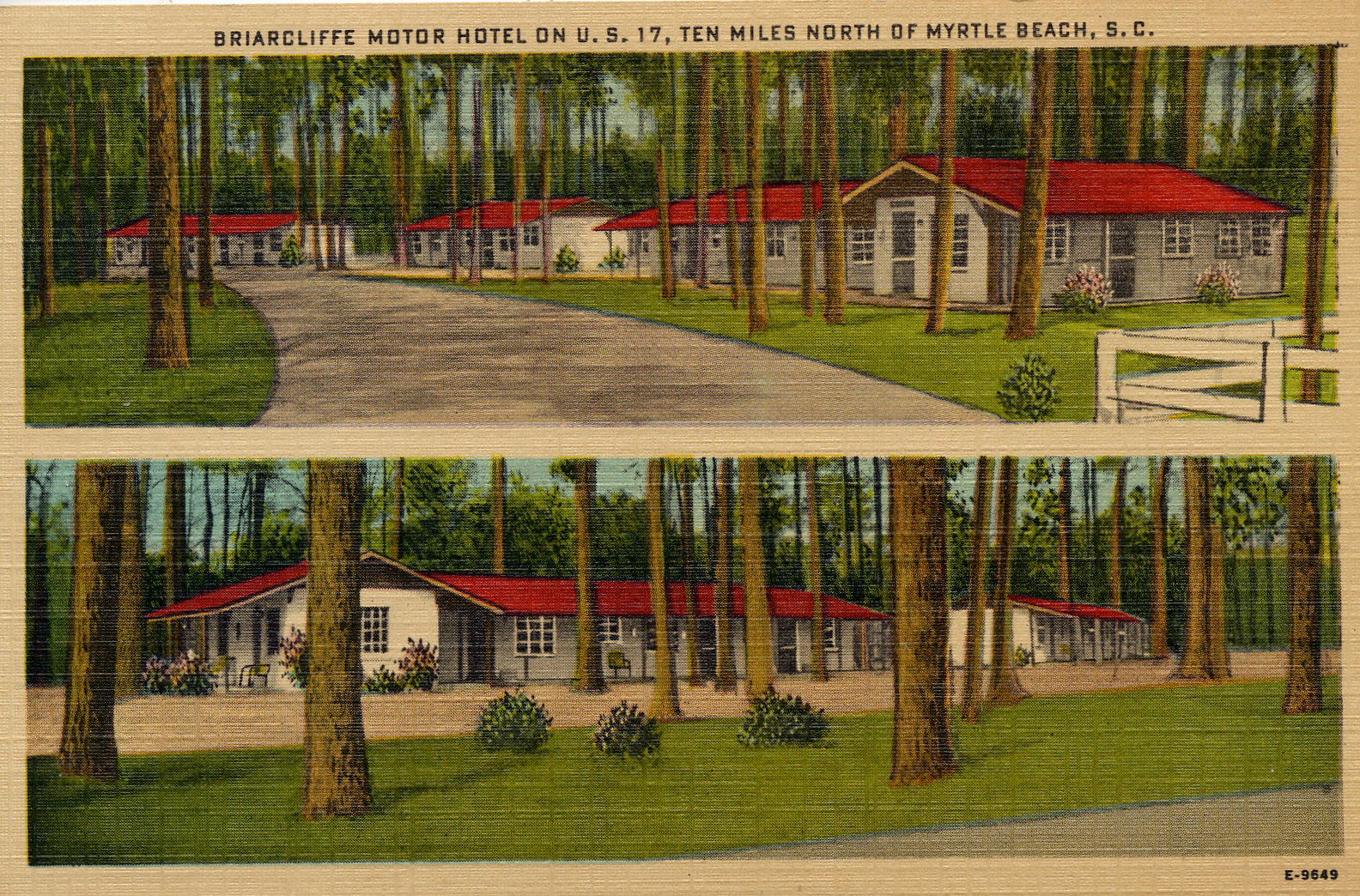

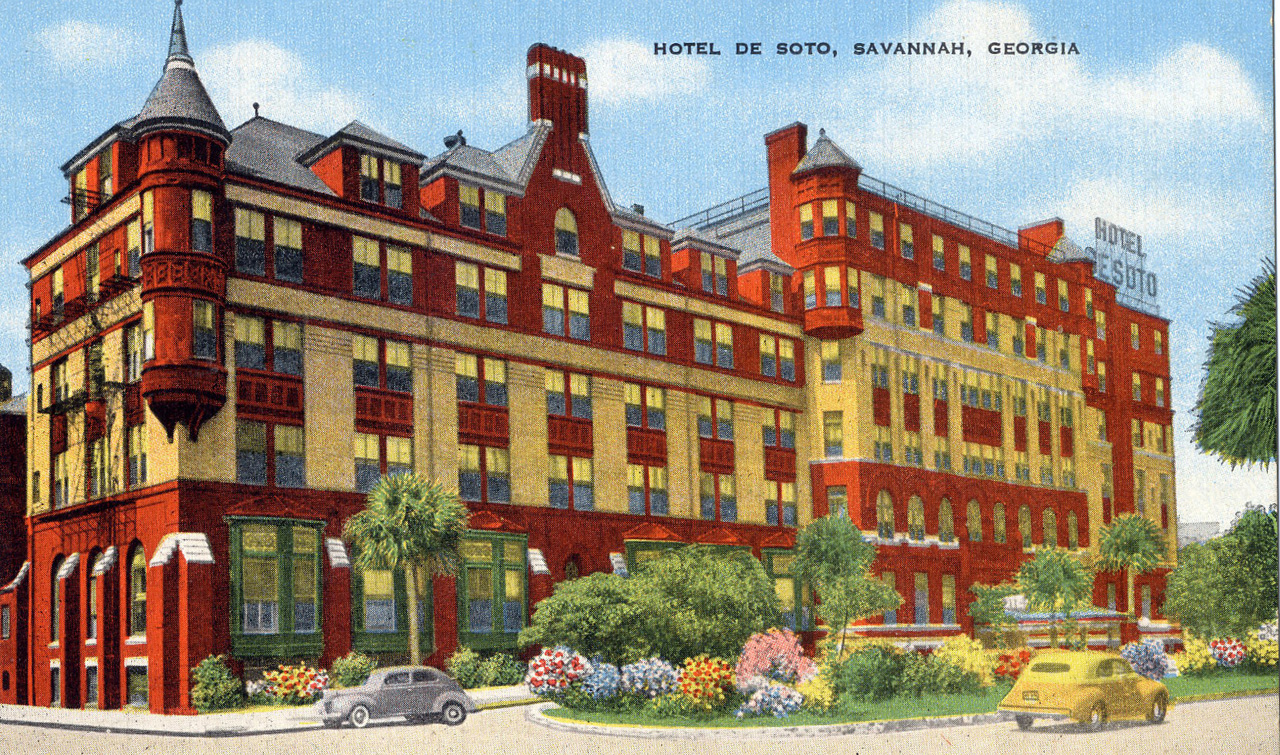

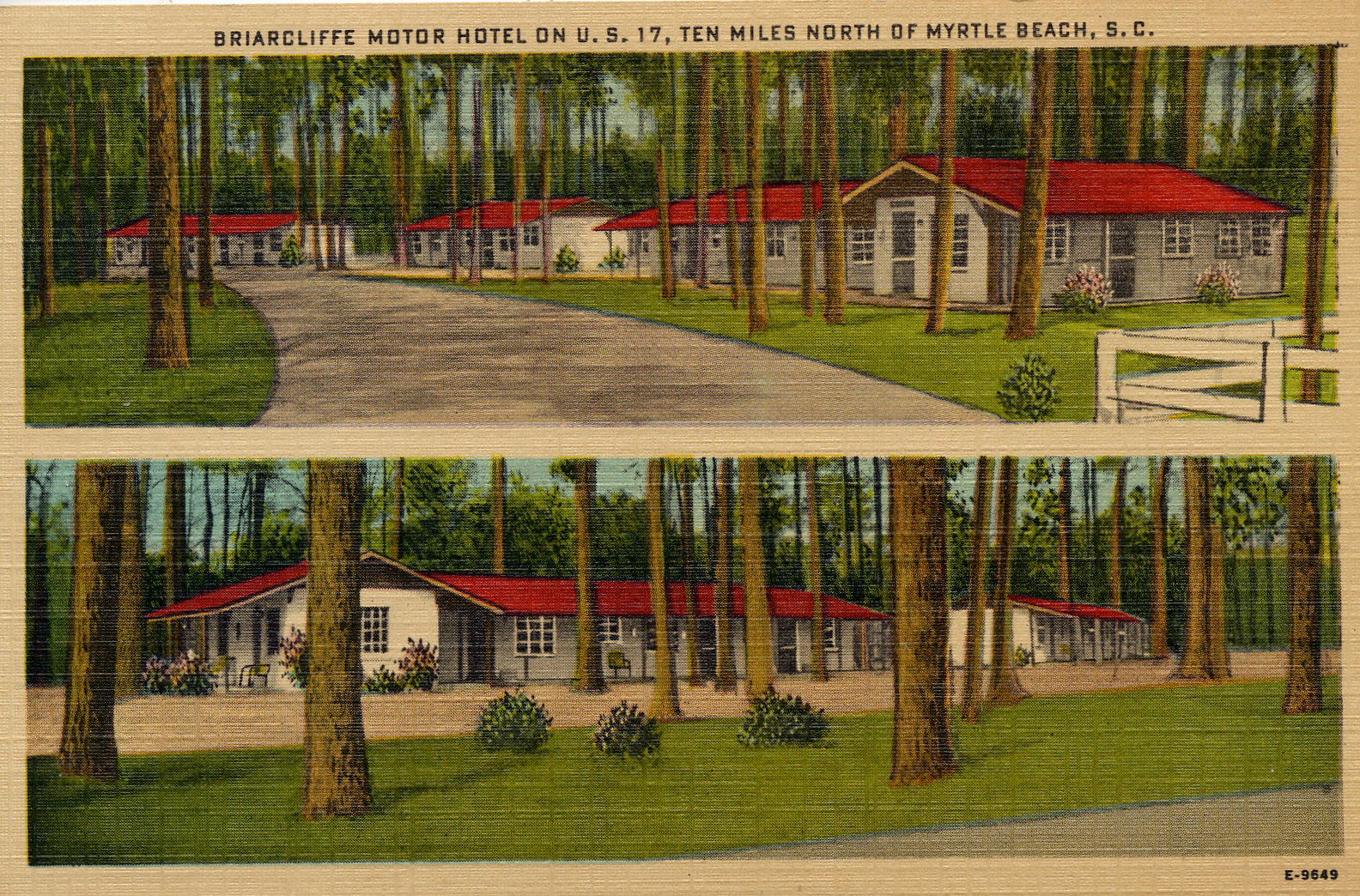

These are scenes from the part of the world you miss now as you whizz down to Florida on I-95.

There's still a hotel DeSoto at this address in Savannah, but it's a Hilton now and it looks nothing like this as far as I remember. Must have been a fire or something.

Route 17 is the old Ocean Highway; it runs through some of the most extraordinary Spanish moss country along the Georgia coast. You can turn off it down near-dirt roads and find some of the best food imaginable. We like to linger there when we drive down South.

Two examples of the first generation of resort hotels in America:

Old Orchard House opened in 1837 in an old farm house and soon was serving summer vacationers from as far off as Montreal. The owners built a big new hotel for 300 guests. It burned down in 1875, but they replaced it with this 500-guest version.

As this photo shows, the idyllic view above is somewhat deceptive: The walkway runs down, not to the beach, but to the railroad station that brought the tourists to town.

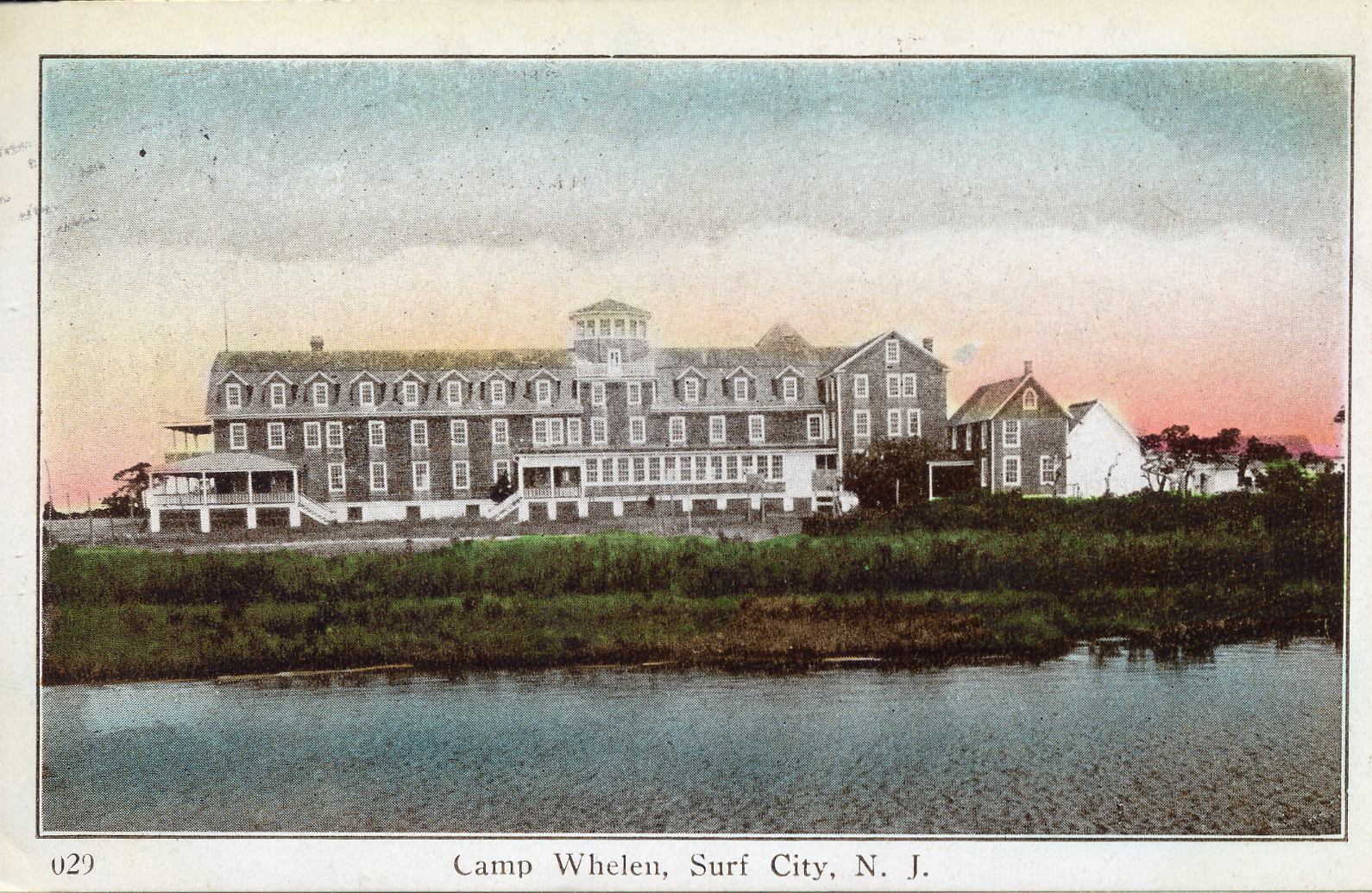

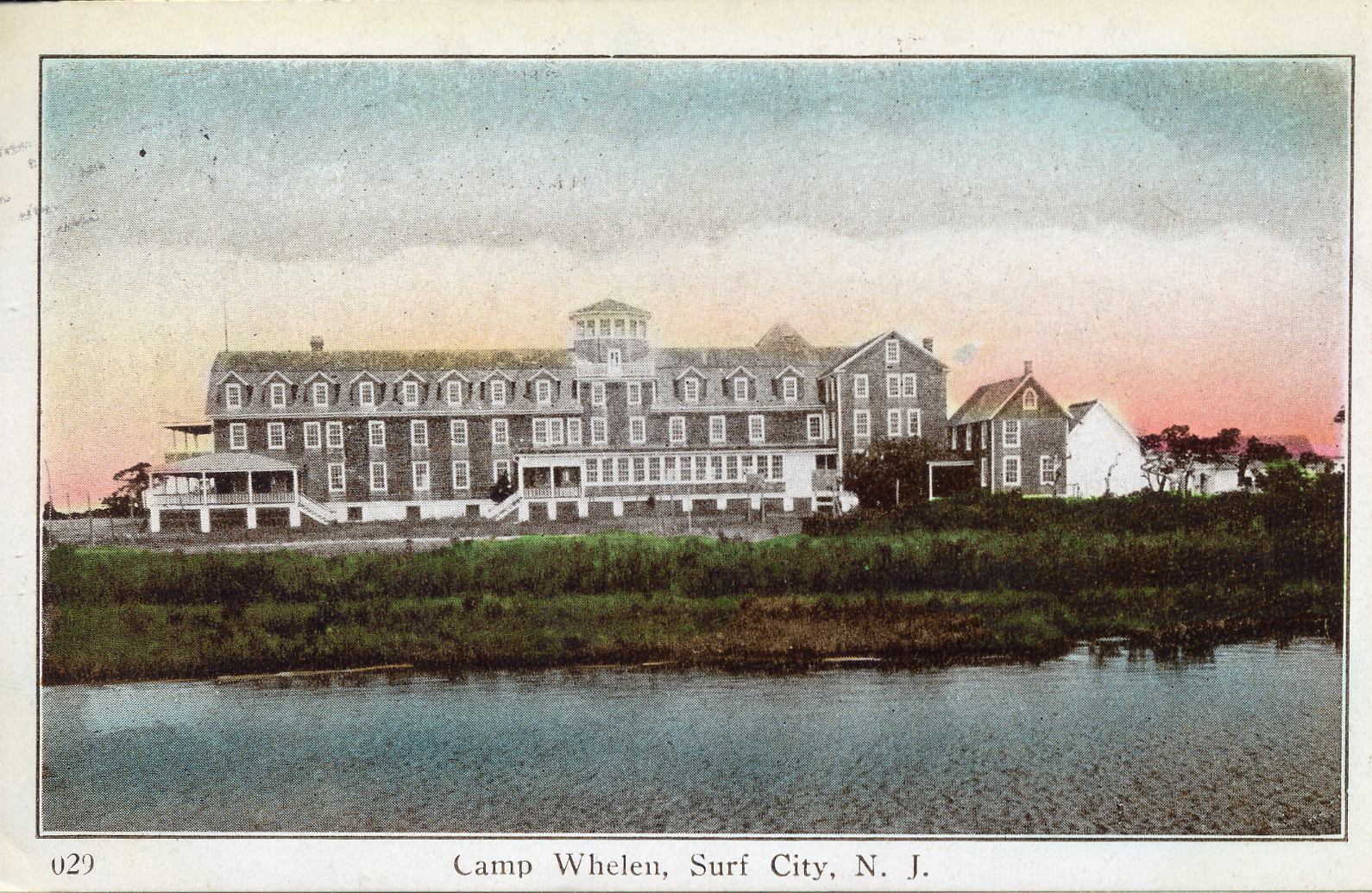

Unlike most of the Jersey Shore postcards I have, the building in this one is still there It's the sole survivor of the golden age of grand hotels on Long Beach Island. The "borough of Surf City" where it was built originally was a region known as "Great Swamp." You have to think the real estate prospects were improved by the name change.

The core of this old hotel seems to date back to the 1840s, and it was known as Harvey Cedars Hotel in its heyday in the late 1800s. This photo shows it as it was when the Philadelphia YWCA ran it as a women's vacation resort. The camp foundered in the Depression.

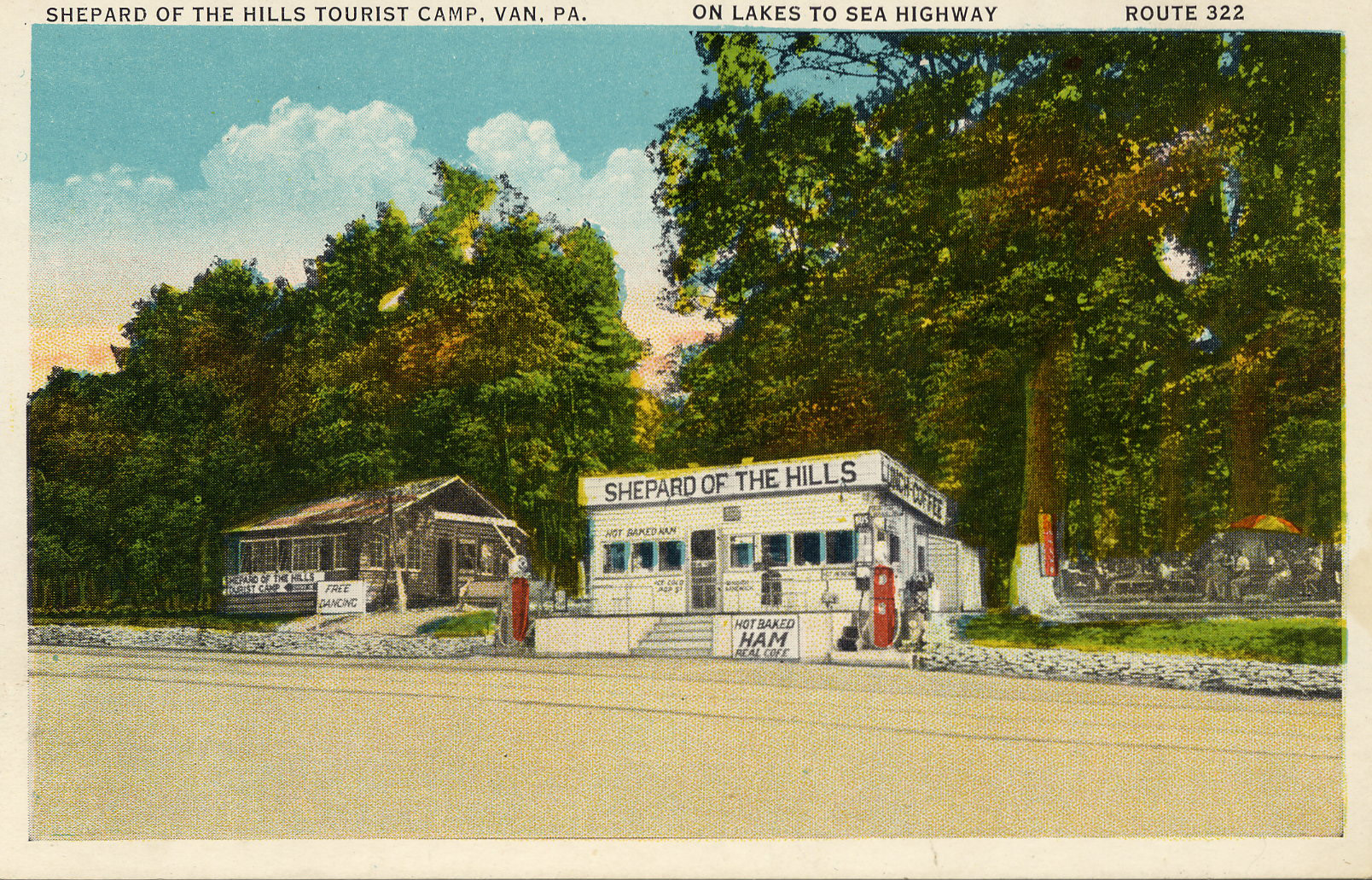

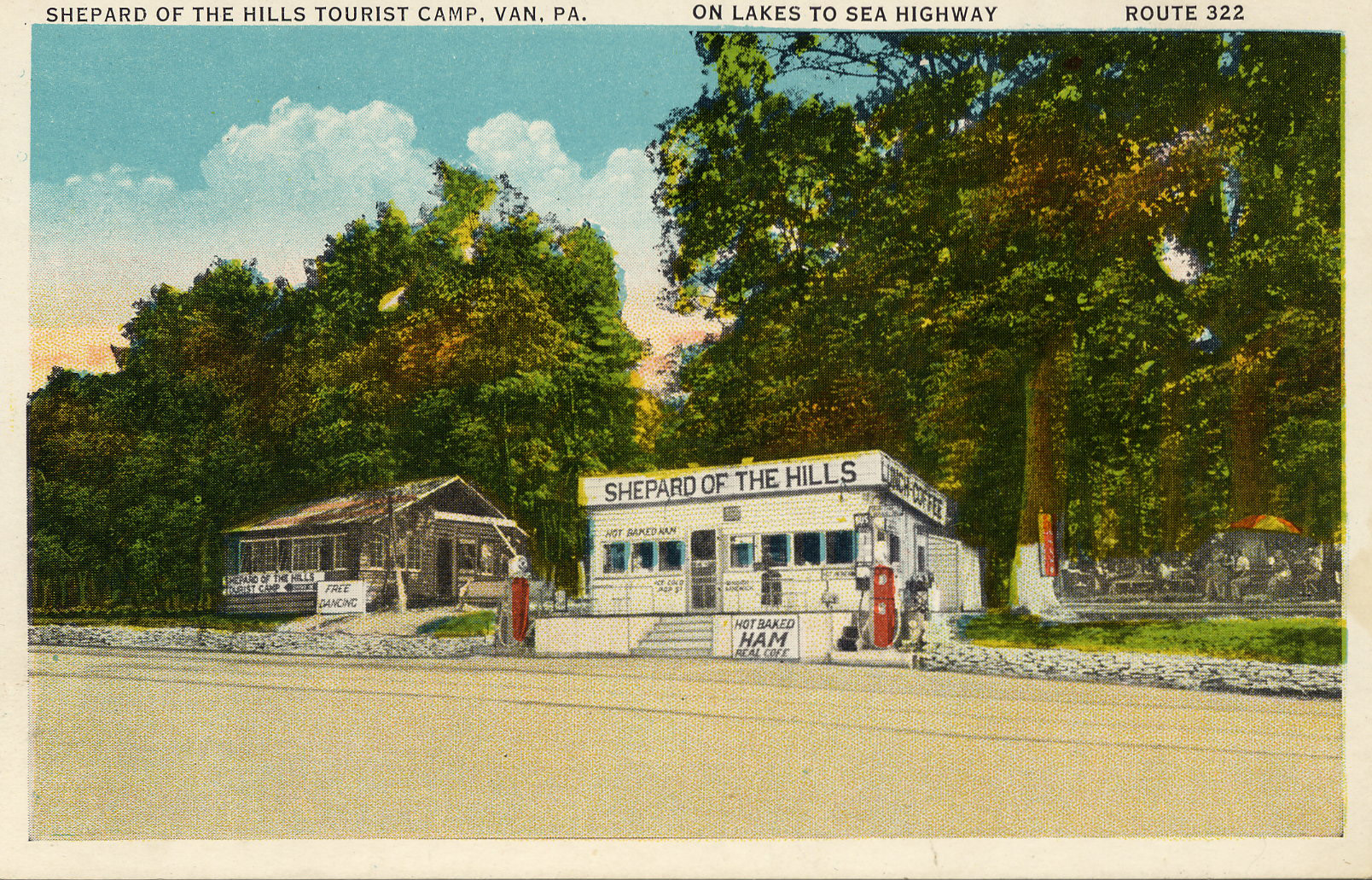

This is a prize. It really does say "Shepard of the Hills," right? I'm not misspelling that? Then again, the owner really does seem proud of that "hot baked ham." And the "real coffee" As opposed to? "Free dancing." As opposed to? Perhaps this also was the first campsite owner to conceive the brilliant plan to whitewash the tree trunks to keep his predictably drunk patrons from ramming into them.

I've lived in Pennsylvania most of my life, and I never heard of a "Van" except the one in Turkey. The "Lakes to Sea Highway" is a reminder of the pre-Eisenhower interstate system, when the government took a lot of random state roads between one place and another and connected them with lines on a map and gave it some grandiose name.

Another one. Nothing written on the back, and I don't really know what one would write on the back of a postcard of the Milwaukee court house. "Wish you were here"? No, probably not. "Food is great. Having a wonderful time. Promised a police escort to state line"?

Downtown Reno, Nevada, and another scenic view of a courthouse. It makes more sense here than in Milwaukee, though. That is, a vacation in Reno is more likely to involve a courthouse angle. I like how the bored artist at the postcard factory amused himself by painting highly improbable yellow, red, and blue hubcaps on the parked cars.

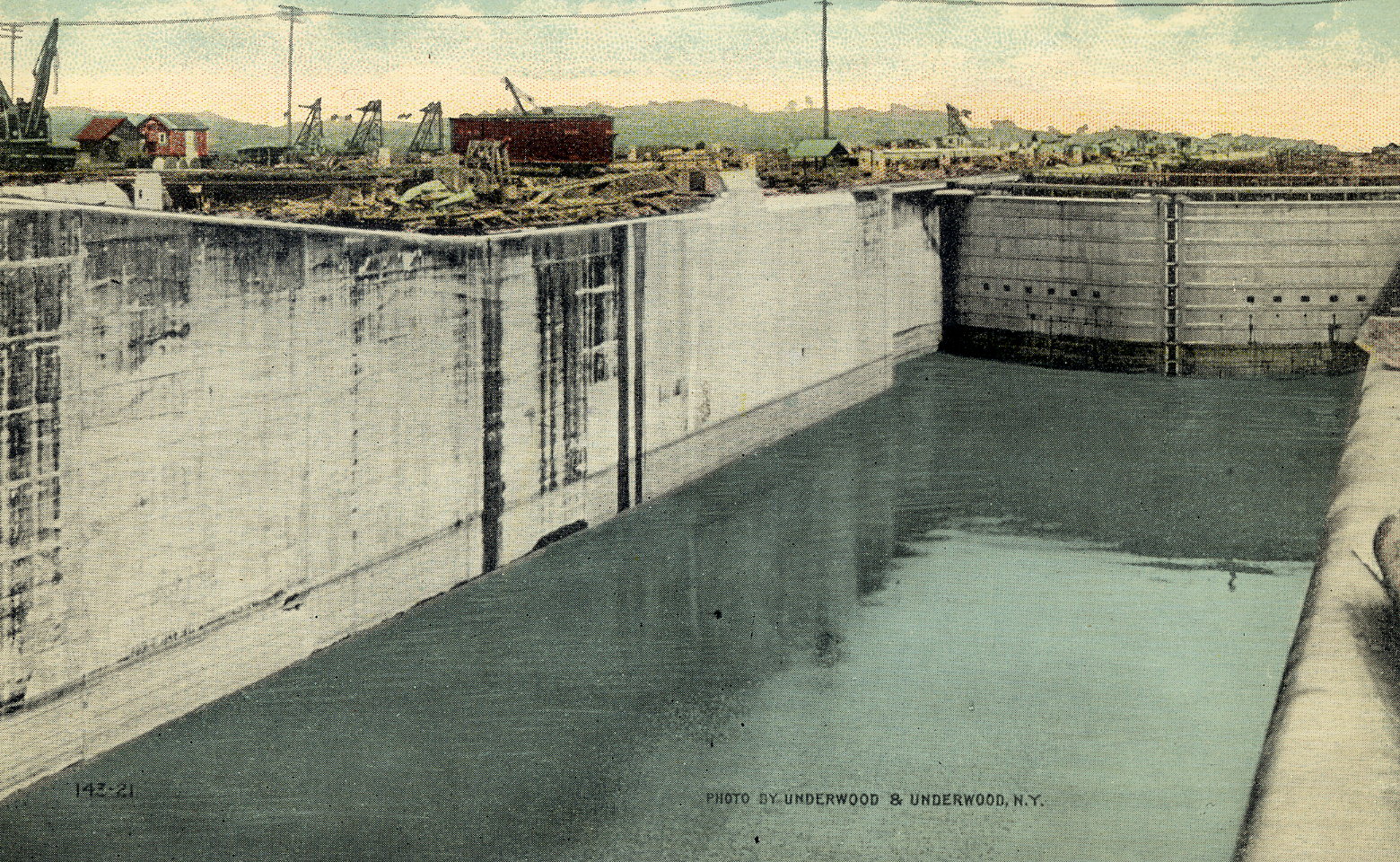

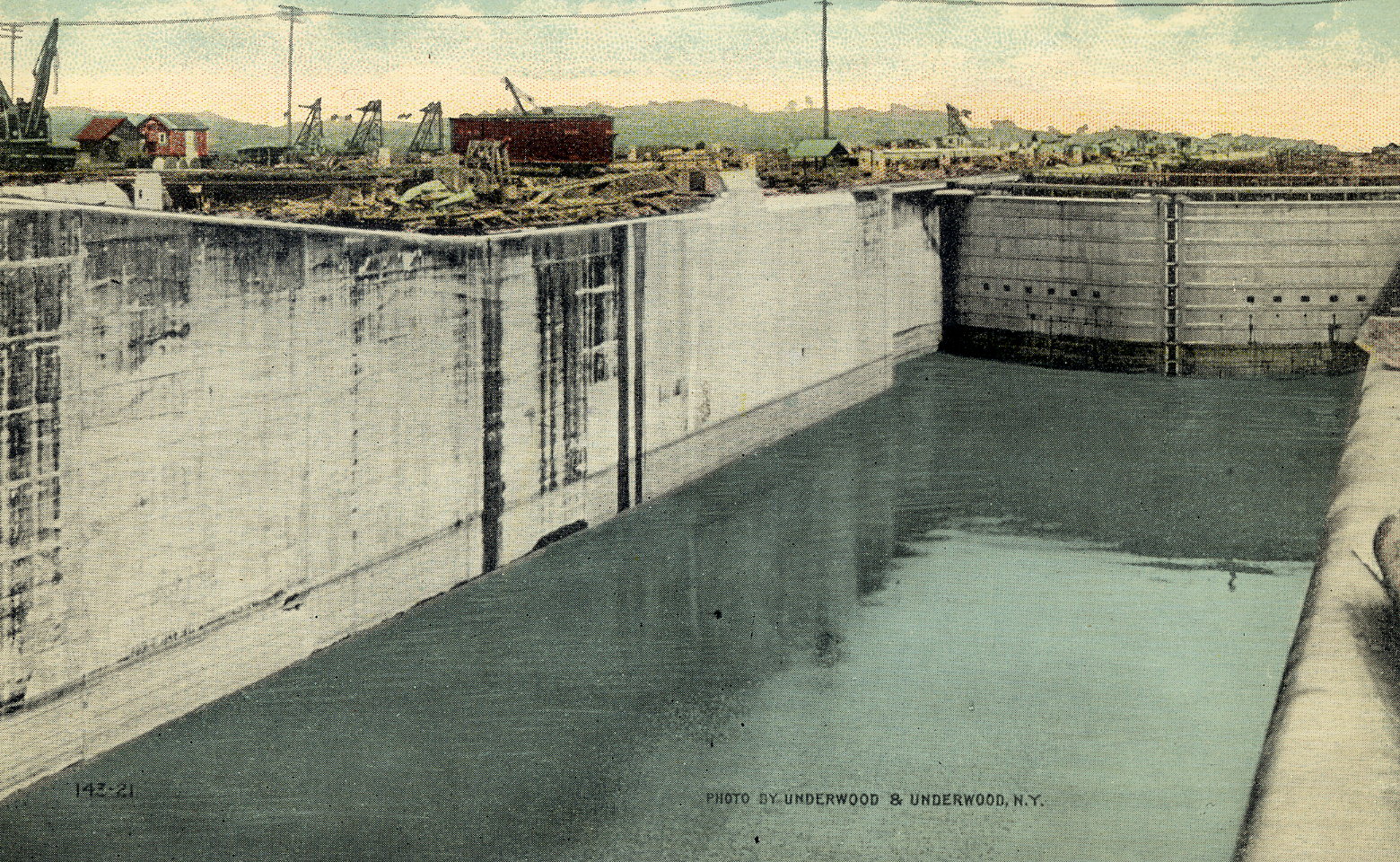

The Panama Canal under construction. Possibly the most boring postcard of all time. The little blurb on the back says, "The progress of the Panama Canal has been so rapid that it is almost ready for the ships of commerce that will use this gigantic sluiceway that has made two hemispheres out of one." Trying to compensate with breathless prose for what is essentially a colorized black-and-white photograph of standing water.

Of course, if the modern Western media were a postcard company from the turn of the last century, it would be a picture of dead coolies and a headline about Roosevelt lied and an editorial asserting that this whole pointless adventure was a waste of life and international goodwill.

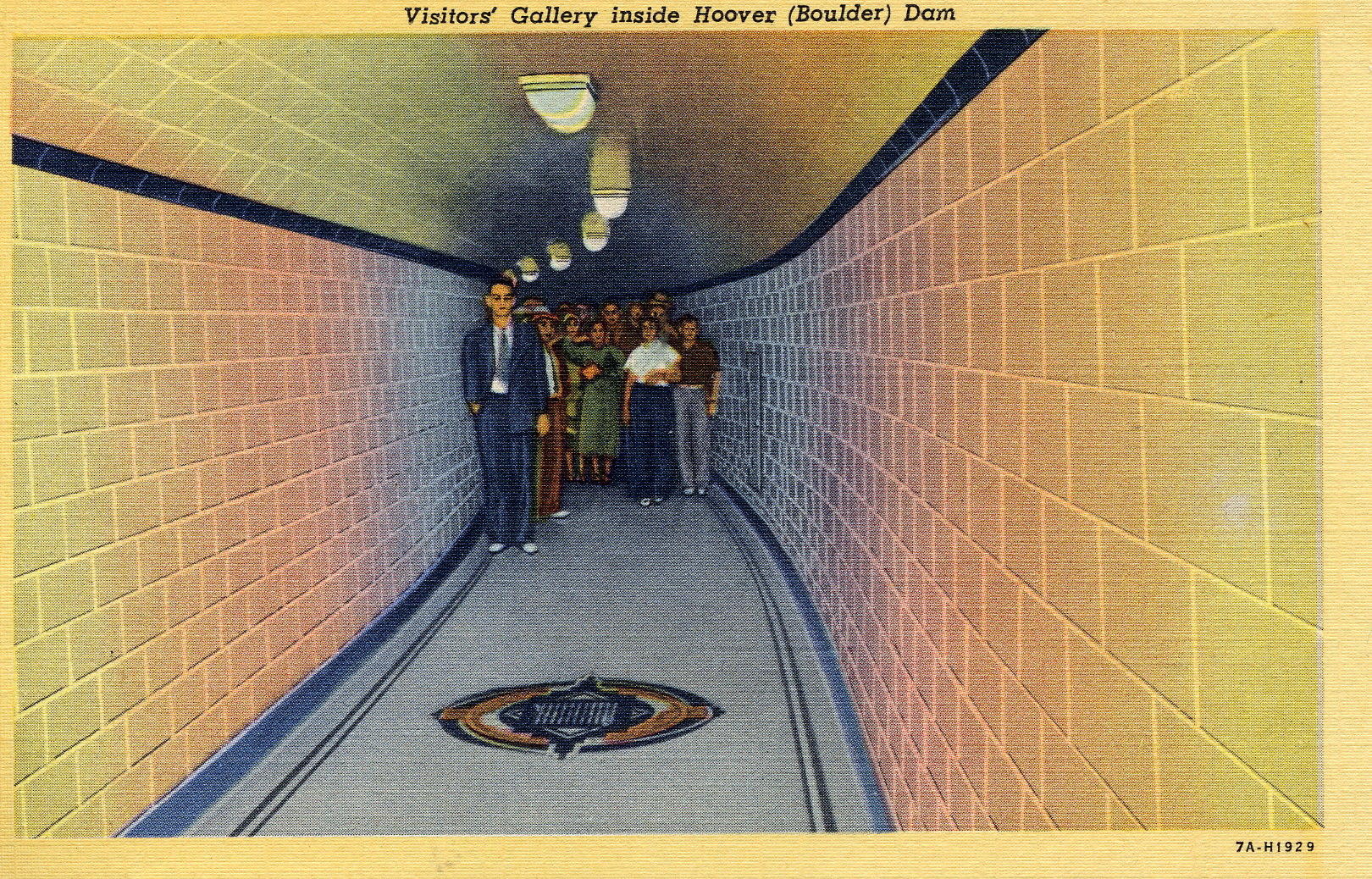

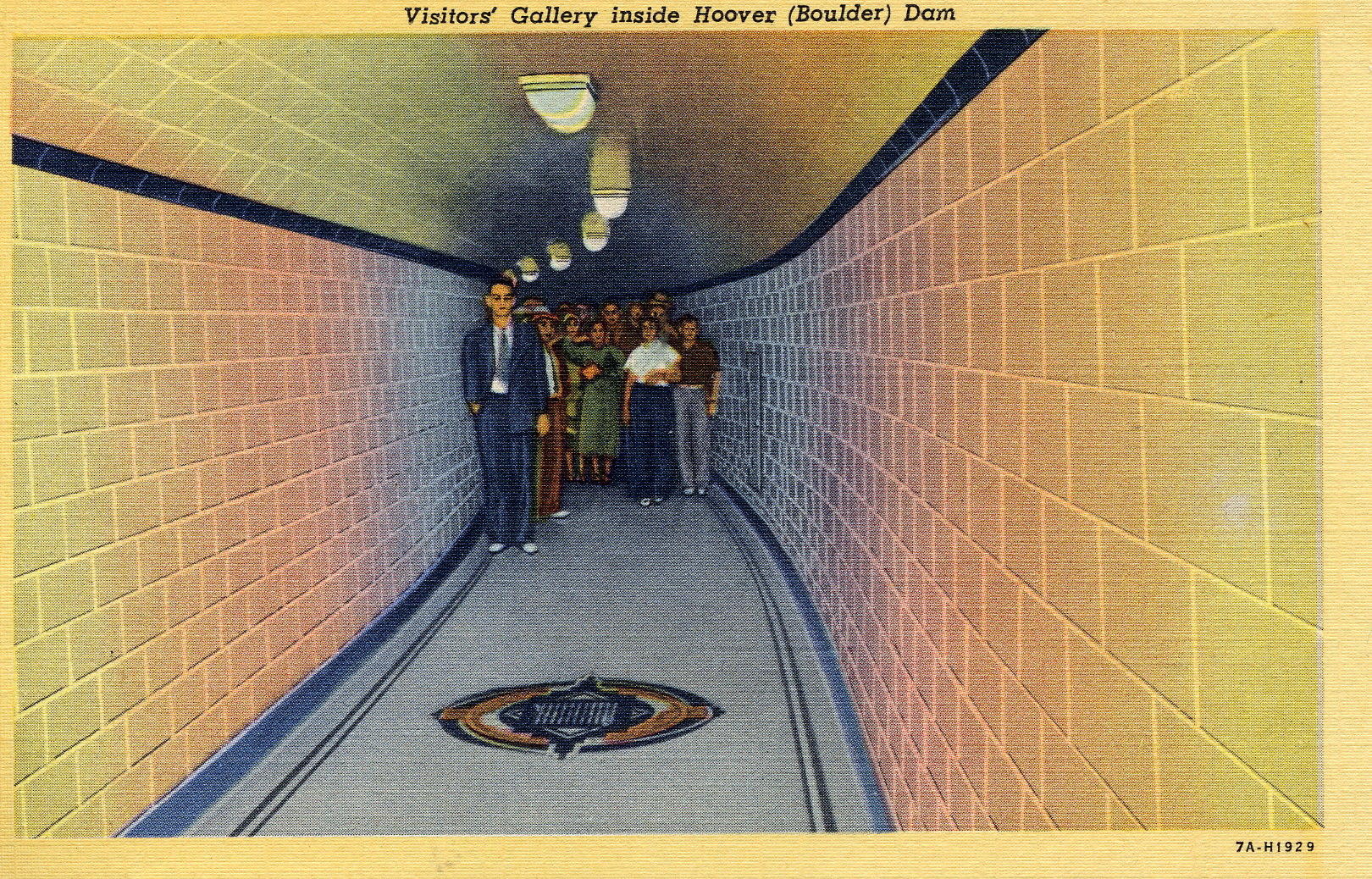

Visitors in one of the galleries of the Hoover Dam. The blurb on the back calls this "one of America's great visitors' attractions," and with a boost from this psychedelic watercoloring job it's almost convincing. What a disappointment, though, when little Johnny gets there and discovers, "Aw, gee, mom, it's really just all a lot of gray concrete."

The postcard says more than 2.5 million people have been through here. This lucky group just happened to be passing through when the cameraman set up his tripod, and thus have been apotheosized into scrapbooks all over the land. Too bad for us it was a tour group from some pre-Civil War sect that refused, on theological grounds, to smile for cameras.

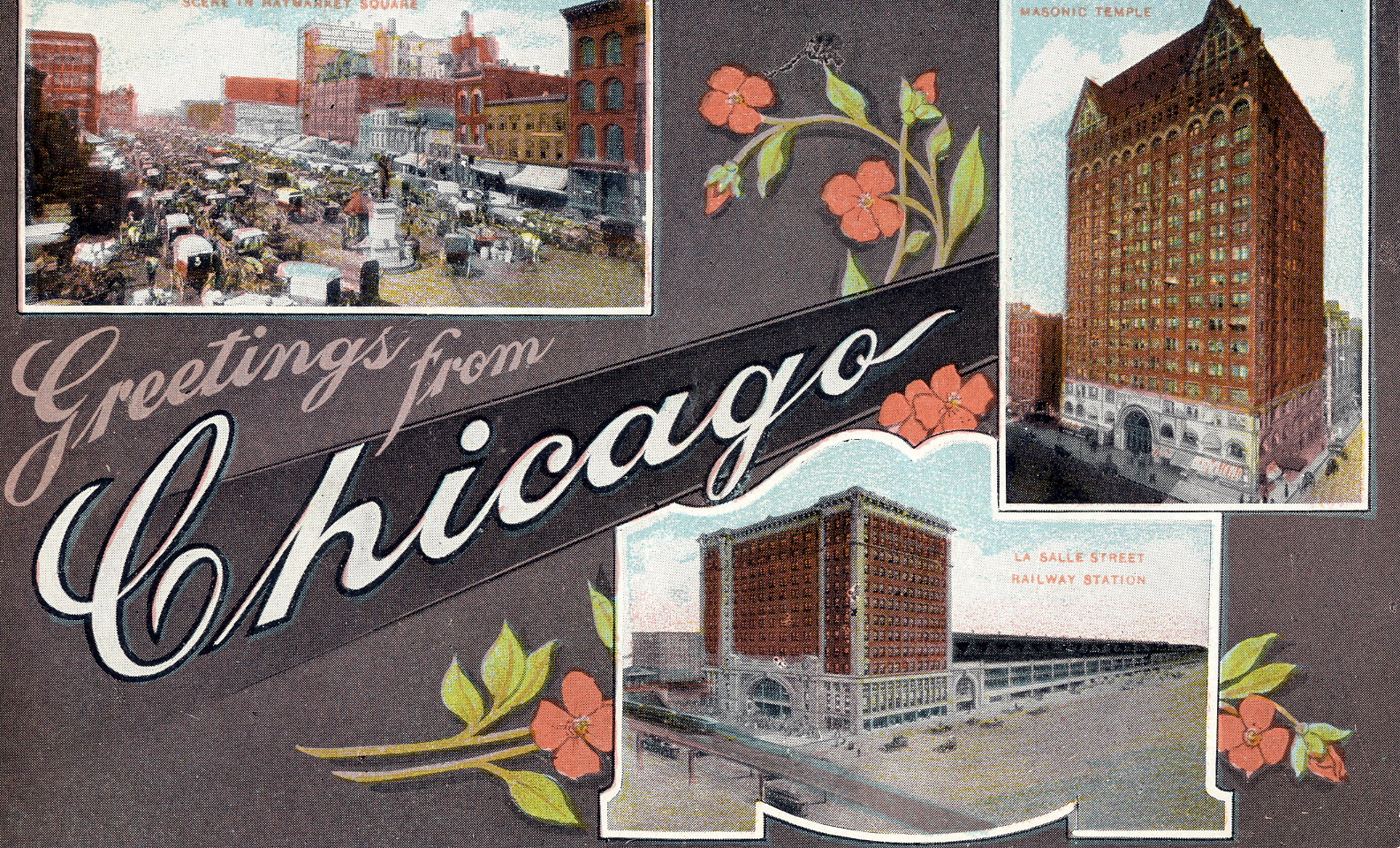

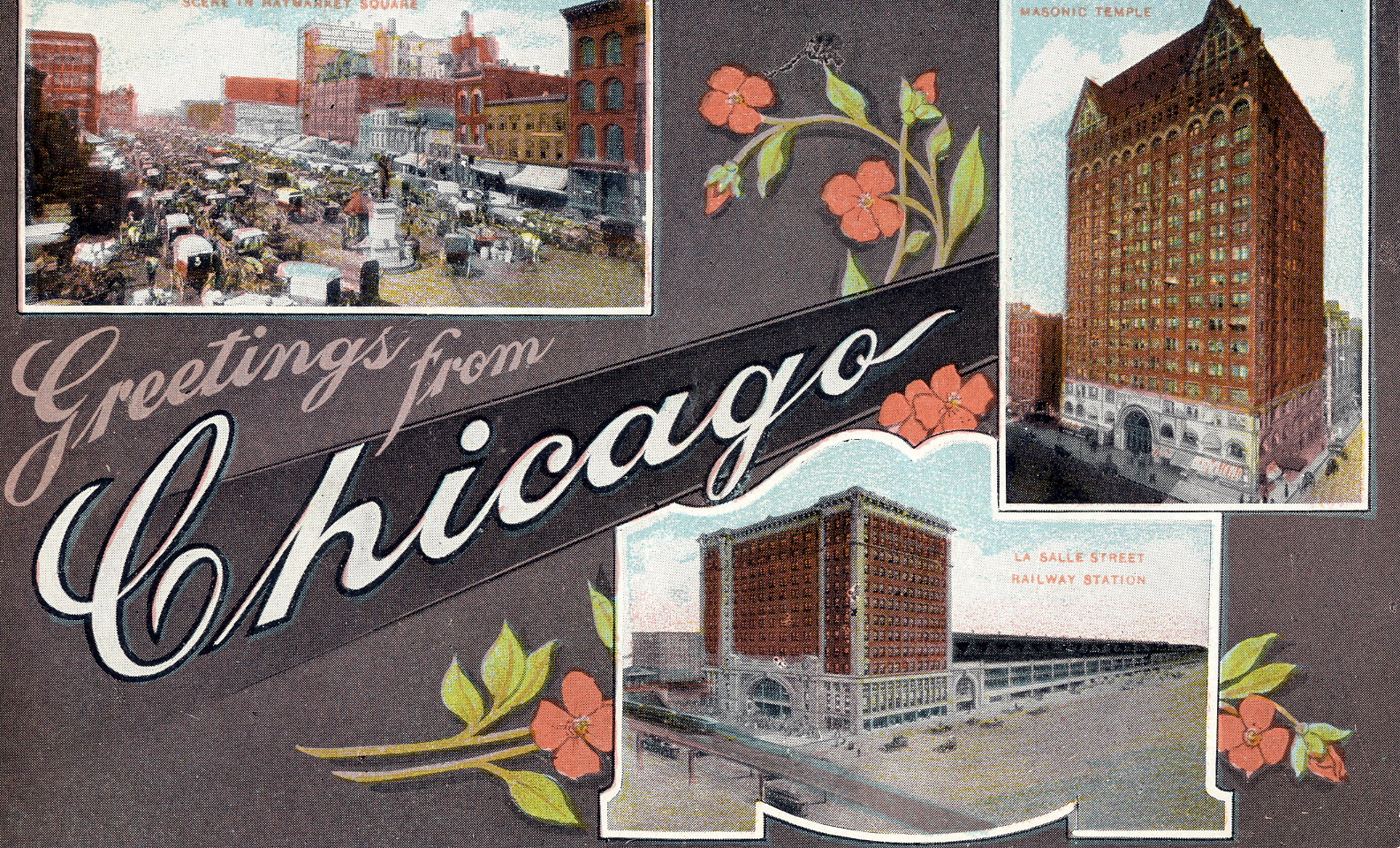

A couple for you Windy City fans:

Back from the day when the Masonic Temple and the railway station and the market -- for chrissakes -- were the city's architectural wonders.

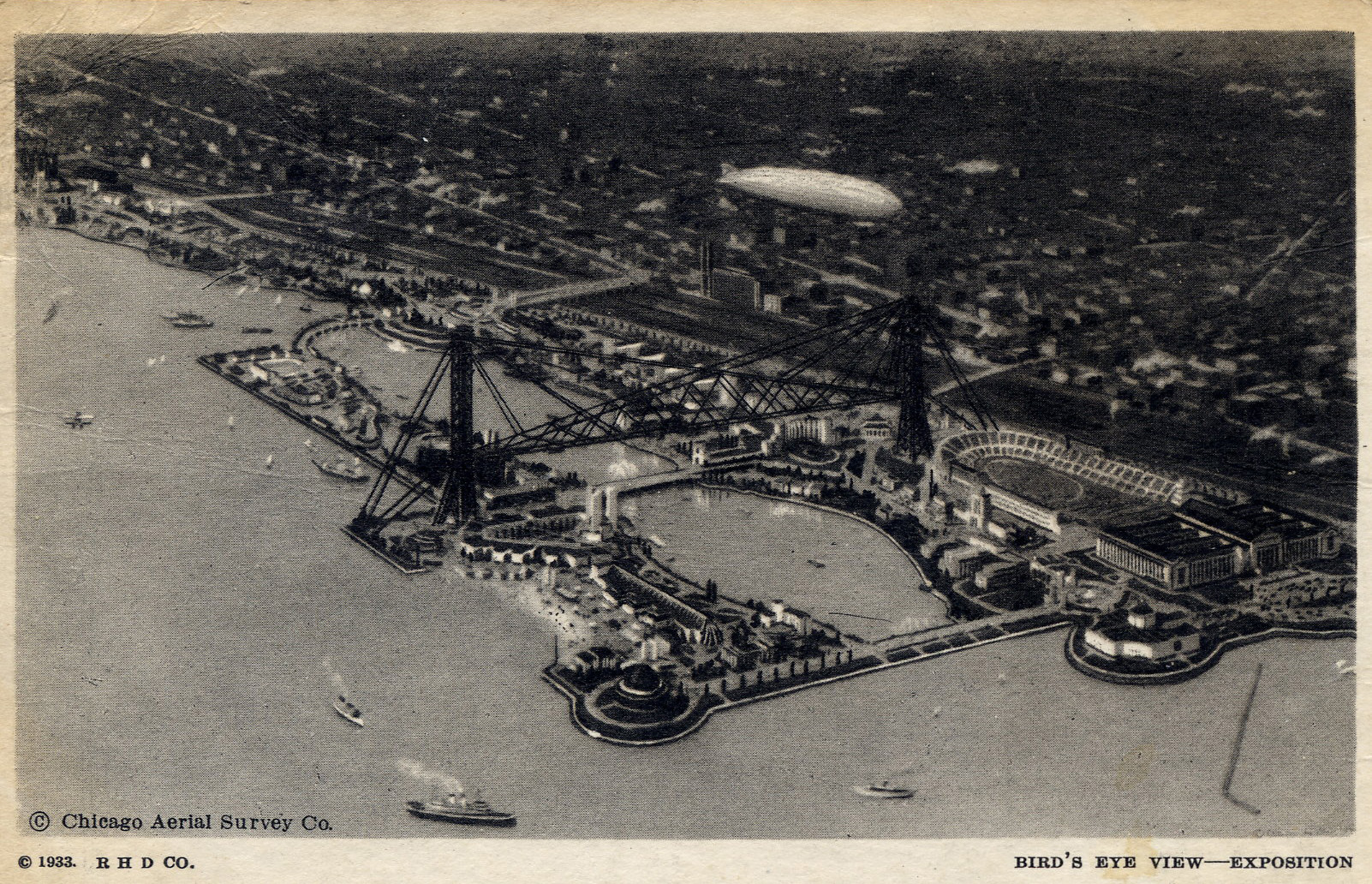

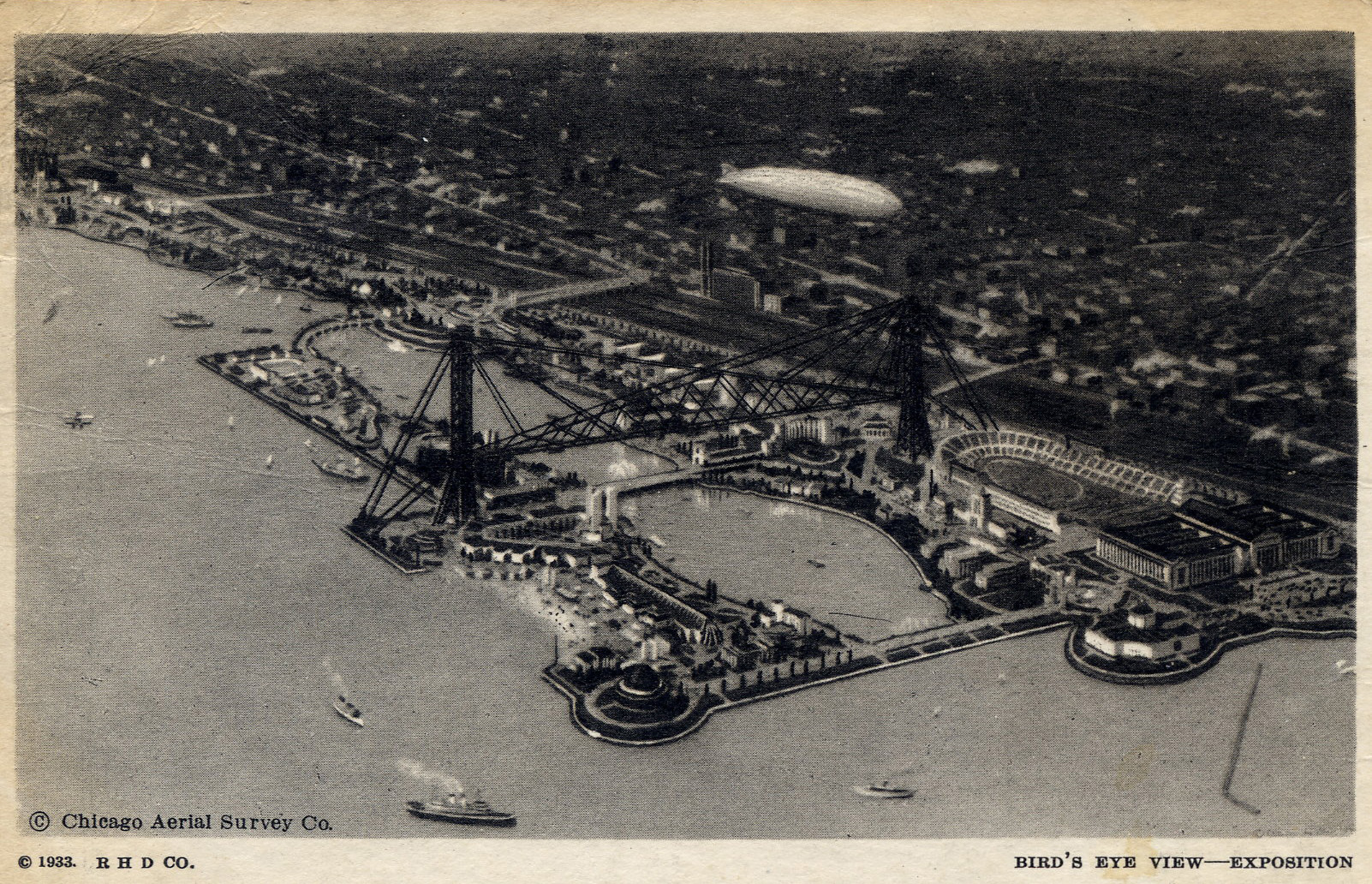

An aerial view of the 1933 "Century of Progress" exhibition. Any of this still there? I guess the great dirigible of time has moved on.

Care to guess on a date? I was thinking mid-1940s by the cars and the dress styles, but then I looked closely at the marquee at the Loew's State Theater, and you can see enough of the second feature title to make out what I guessed to be "Dr. Kildare Goes Home", which turns out to be a real film, released in 1940.

The Loew's State was a classic big theater in mid-century. But, according to the site linked above, it converted to Spanish-language films in 1963, fell victim to urban decay, and wound up a church.

According to this site, the Loew's State offered vaudeville as well as film (not uncommon in the teens) "enhanced by its own orchestra and chorus line." It said Judy Garland made her Los Angeles debut here as one of the Gumm Sisters in 1929.

Here's another view of the corner, taken a couple of decades later.

Street scene postcards seem to have been pretty common. At least, I have a lot of them. Big cities, small towns, it didn't really matter.

Sometimes, though, there's not much there there.

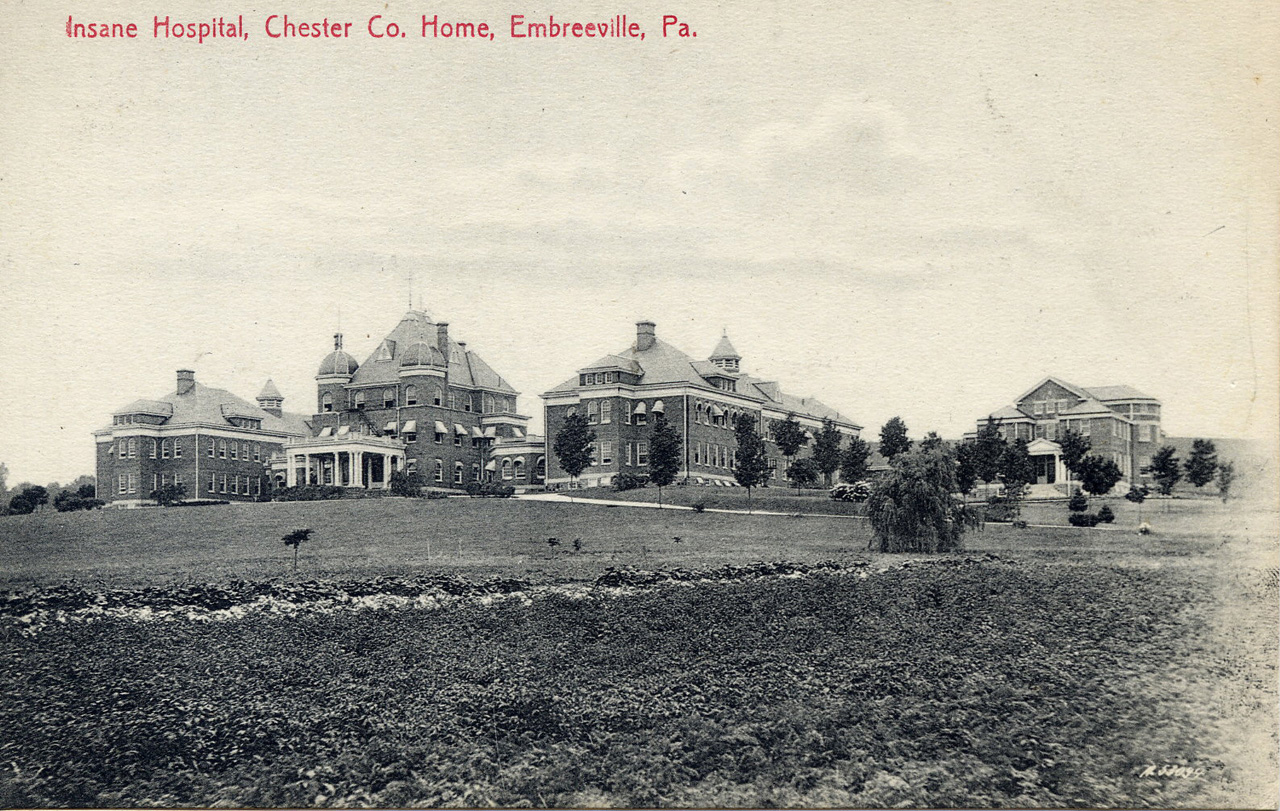

An orphan's home and an insane asylum. More proof that, once upon a time, they'd make a postcard of anything.

And notice, once again, that they're far nicer than a modern apartment building or college dorm.

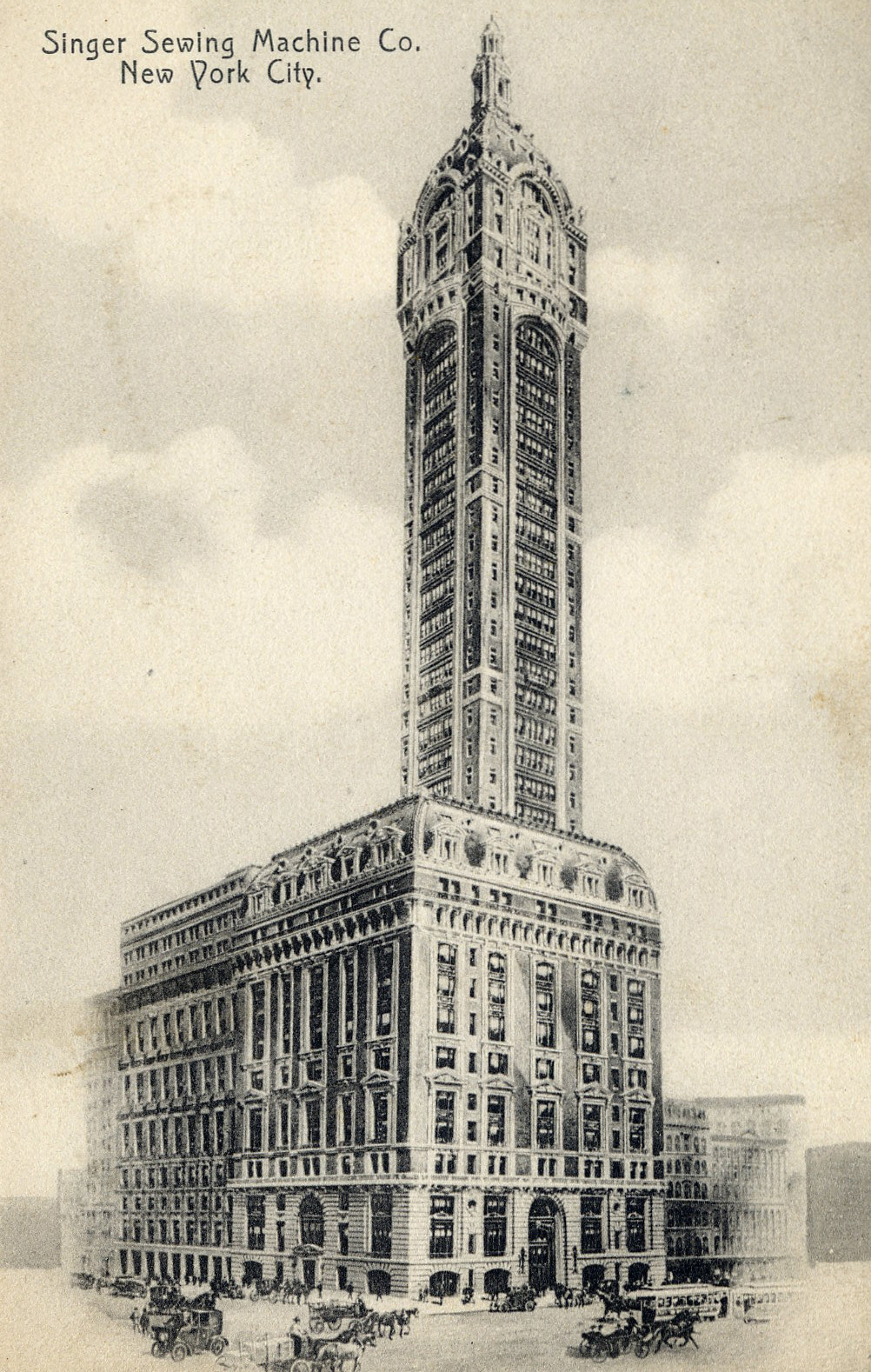

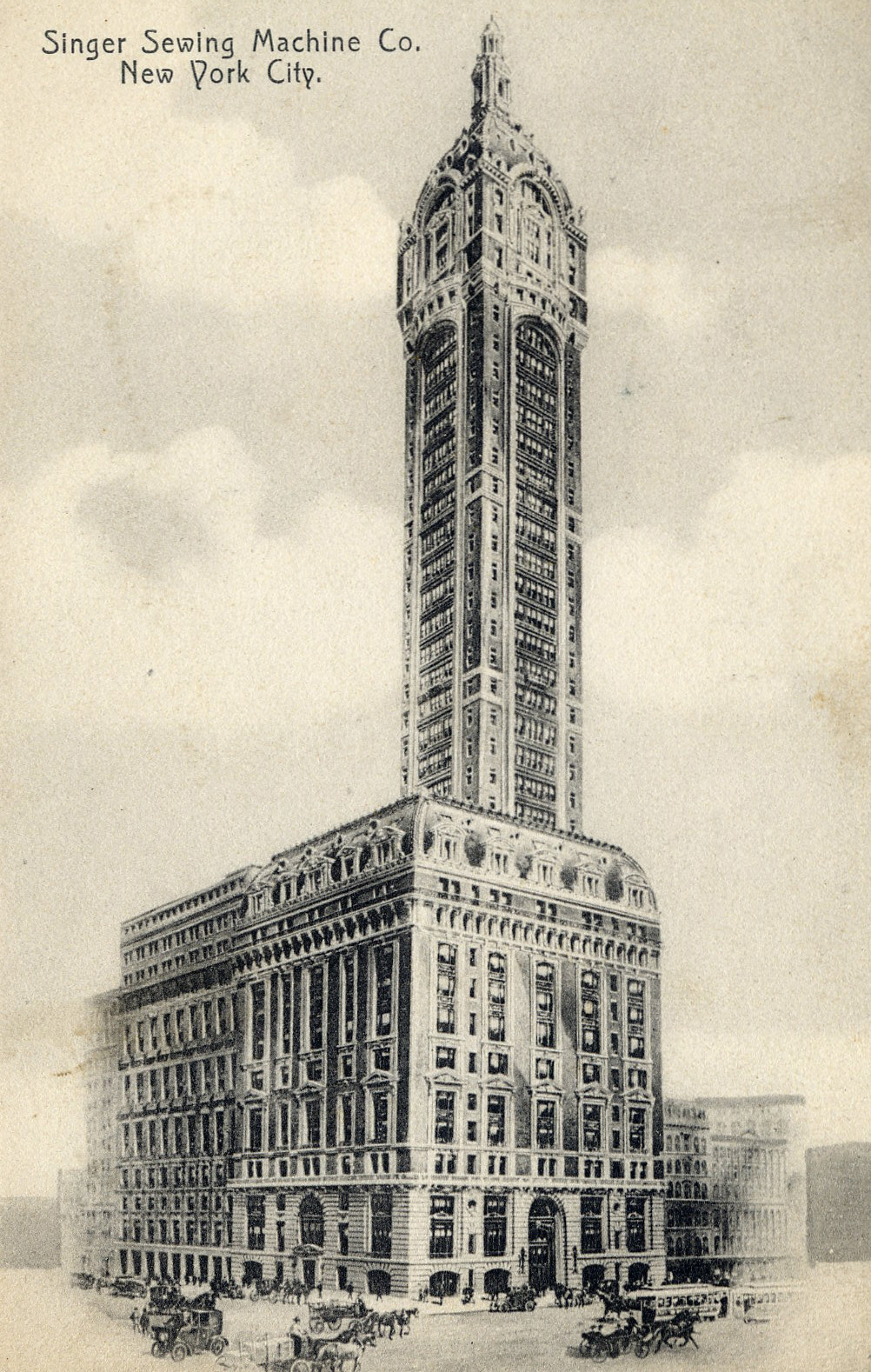

Here is a ghost that haunts me:

This was the Singer Company headquarters, a 612-foot-high tower of Beaux-Arts brick and steel at Broadway and Liberty streets in Manhattan. The architect, Ernest Flagg, loathed the skyscrapers then surging up to claim the profile of New York. Rather than build straight up from the lot lines, Flagg said, why not raise up graceful shafts out of lower-profile buildings? By doing so, he wrote, "we should soon have a city of towers instead of a city of dismal ravines."

The Singer tower, on the remodeled company headquarters, captured that vision. But few followed it.

When the tower was finished in 1908, it was the tallest building in the world. Here's what Manhattan looked like when the Singer was king.

It only held the "world's tallest" designation for about a year, but it remained a famous New York landmark. Singer sold it in 1963, however, and it was torn down to make way for the U.S. Steel Building (now 1 Liberty Plaza). The flaw in Flagg's vision of a city of towers was a simple one of profit and numbers: The total area per floor in the Singer building was just over 4,200 square feet; the floors in 1 Liberty Plaza, a conventional big box skyscraper, measure about 37,000 square feet. Square feet = big bucks.

Demolition of the Singer began in August 1967, just as the new king of skyscrapers, the World Trade Center, was rising up a few blocks to the west. And that's when the Singer building acquired another, temporary, world record. It was, at that time, the tallest building ever to be demolished. That record held until Sept. 11, 2001.

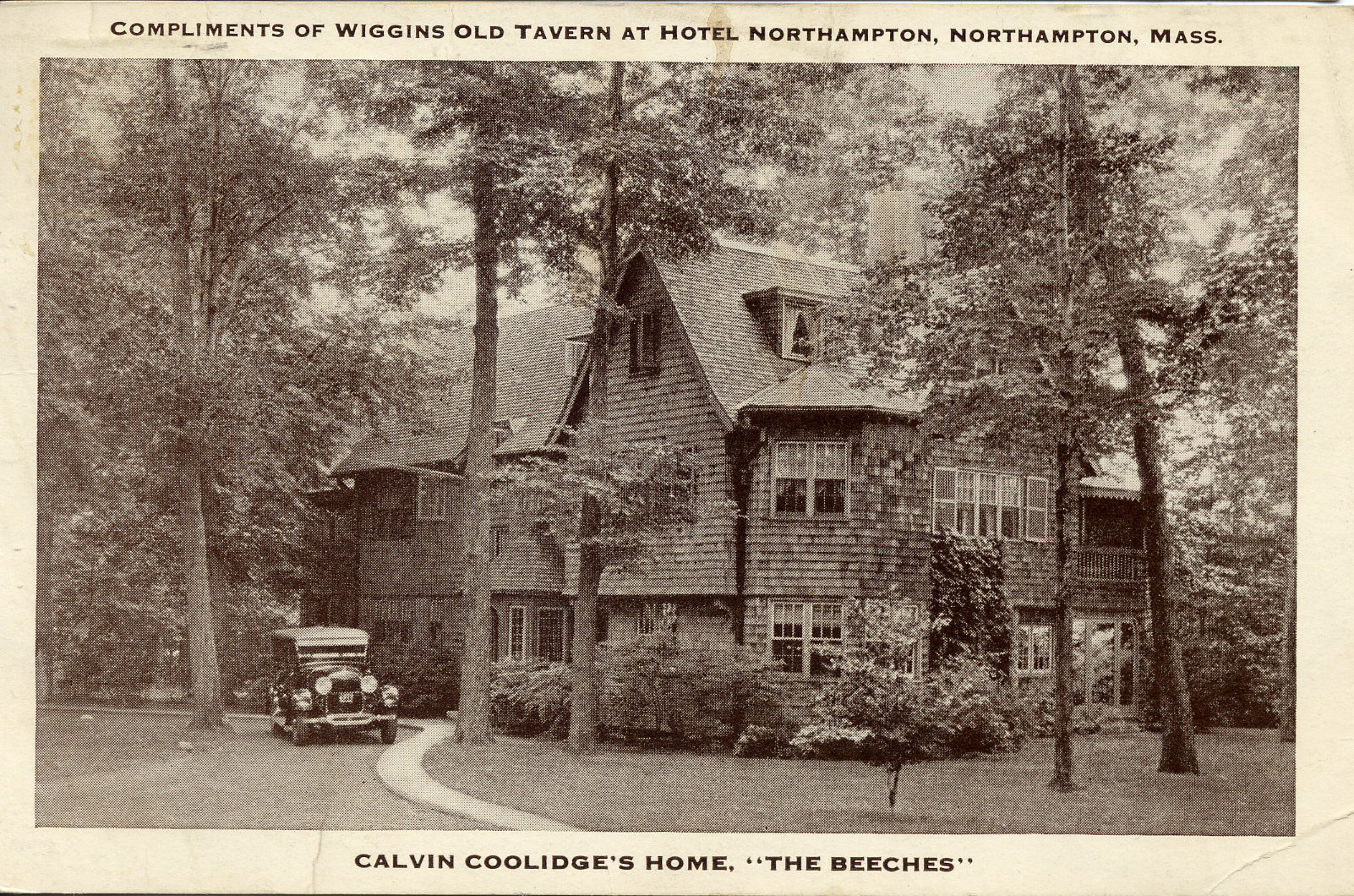

Coolidge was one of the most "misunderestimated" presidents. His image is fixed for us, perhaps by H.L. Mencken's mocking quip that Coolidge was "the greatest man ever to come out of Plymouth, Vermont." His voice was "about as musical as the sound made by a buzz saw," and the man himself was once summed up as "repressed sentimentality chained in a prison of a smooth, flinty New England exterior."

But a couple of stories I've read about him incline me to like him better, differences of politics aside. One hinges on his legendary taciturnity. A lady guest seated beside him at a dinner party said, "Oh, Mr. President, I bet a friend I could get more than two words out of you."

Coolidge replied, "You lose."

I don't know if that one is true or not (and I quote it from memory, so all caveats apply). But it is true that Coolidge is on the list of presidents whose terms were marred by the tragedy of a child's death. The list is remarkably long to us who live now and forget how remarkably common such losses were not so long ago, to paupers and presidents alike.

Lincoln is on the list, of course, as is Coolidge's fellow New Englander Franklin Pierce, who with his wife endured a horrific railway crash two months before his inauguration. Their train-car derailed and rolled down an embankment and the Pierce's sole surviving child, a son named Bennie, was practically decapitated in front of their eyes. Mrs. Pierce never recovered her full sanity and thought the loss was somehow the price God exacted in exchange for the White House.

Coolidge lost a young son to a blood infection that started as a blister. Even in 1924, medicine couldn't save him. The president seemed to take the loss in the same despairing spirit the Pierces had:

Coolidge said, "In his suffering, he asked me to make him well. I could not. When he went, the power and the glory of the presidency went with him... The ways of Providence are often beyond our understanding. It seemed to me that the world had need of the work he could have done. I do not know why such a high price was exacted for occupying the White House. If I hadn't had the office, he may never have died." ... Subsequent to the Coolidges' personal tragedy, Coolidge made it clear that any young boy out at the White House fence who wanted to see him was to be ushered in.

A friend of Coolidge's also lost a young son, to polio. In a book dedication, Coolidge wrote to his friend, "To Edward Hall, in recollection of his son and my son, who have the privilege, by the grace of God, to be boys through all eternity."

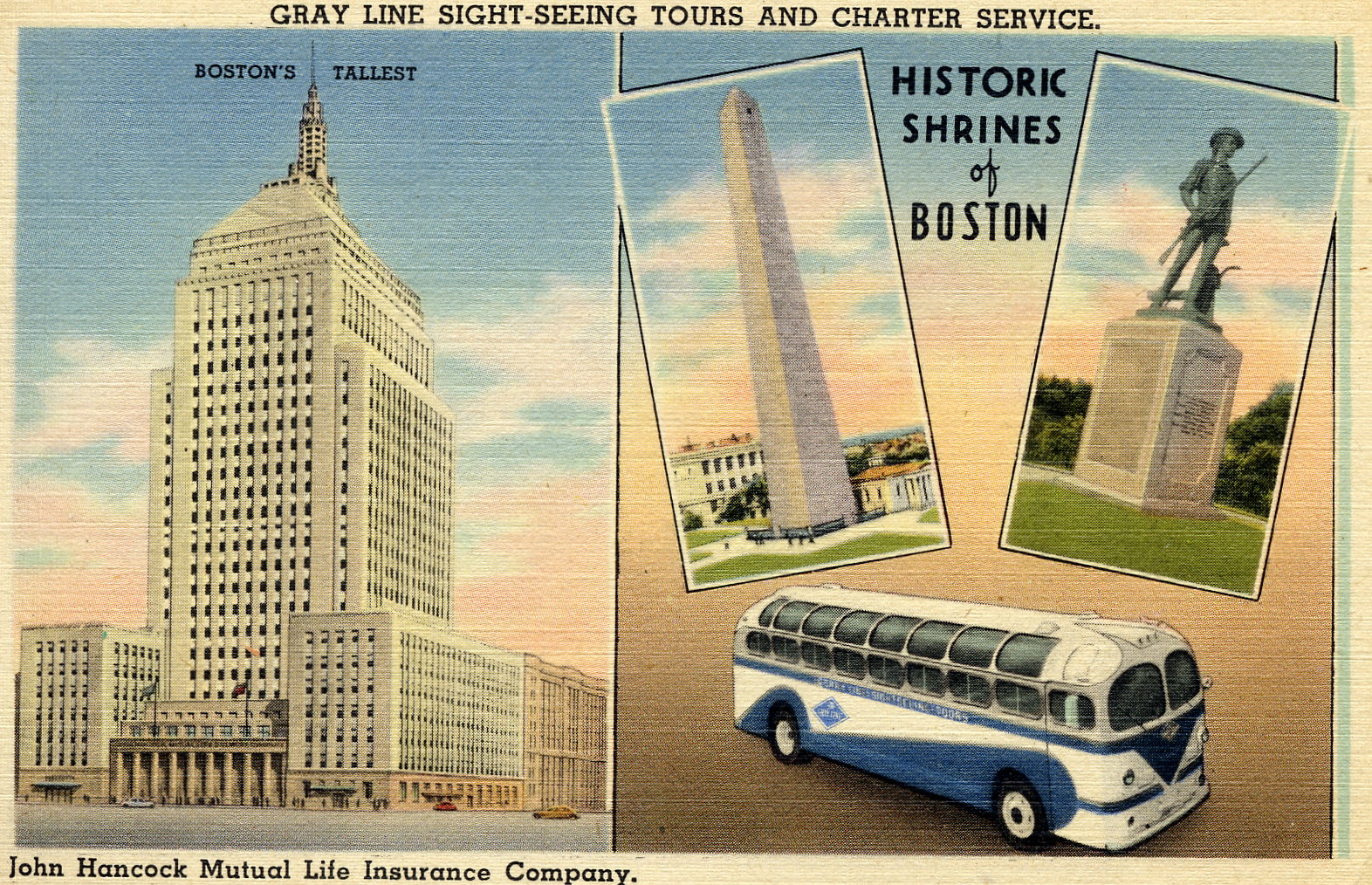

This, on the other hand, strikes me as so full of phallic symbolism as to be borderline obscene -- from the spiking skyscraper to the memorial granite erection to the minuteman's musket to the very wheelwell paint scheme of the Gray Line tour bus.

Now known as The Davis Building.

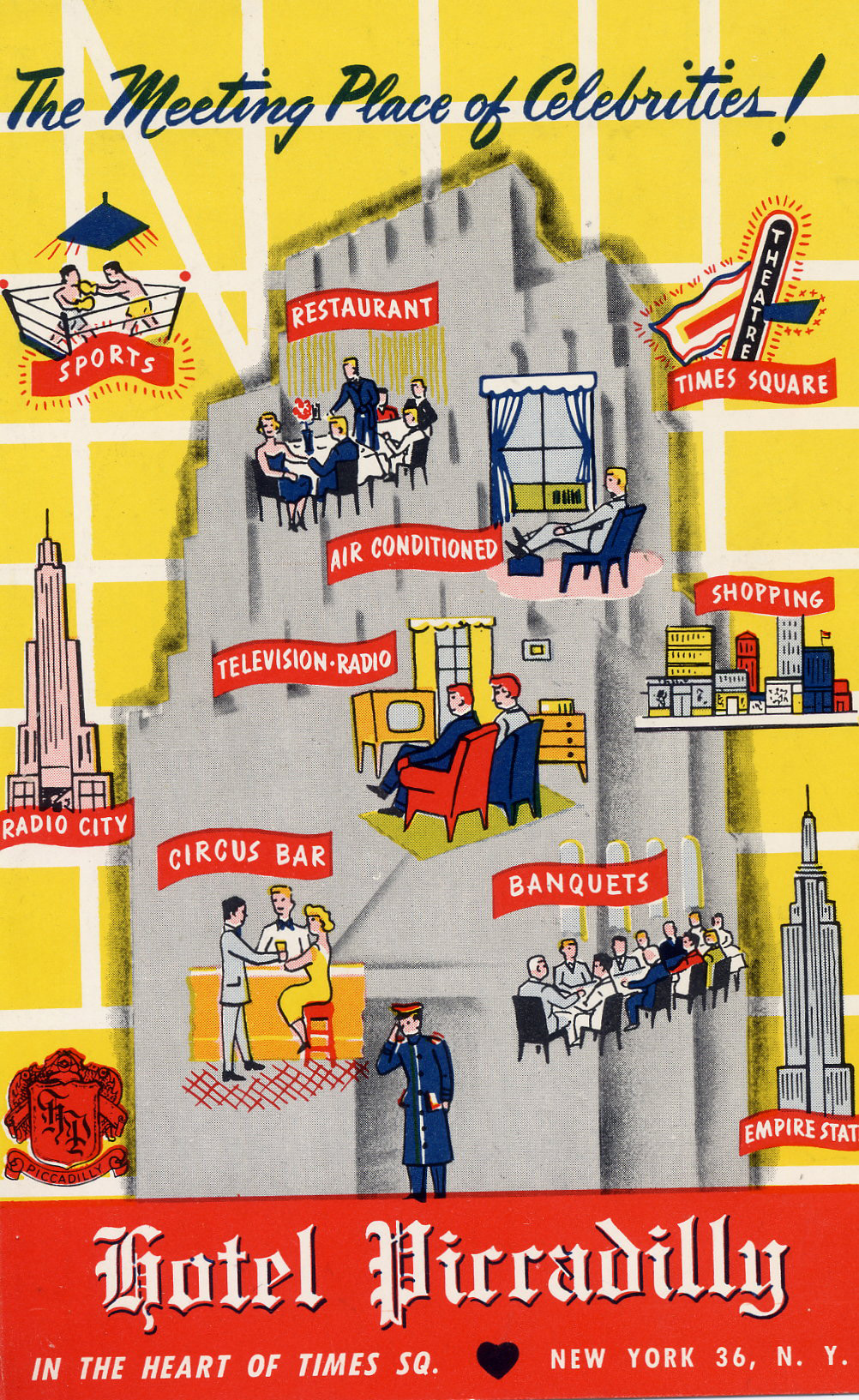

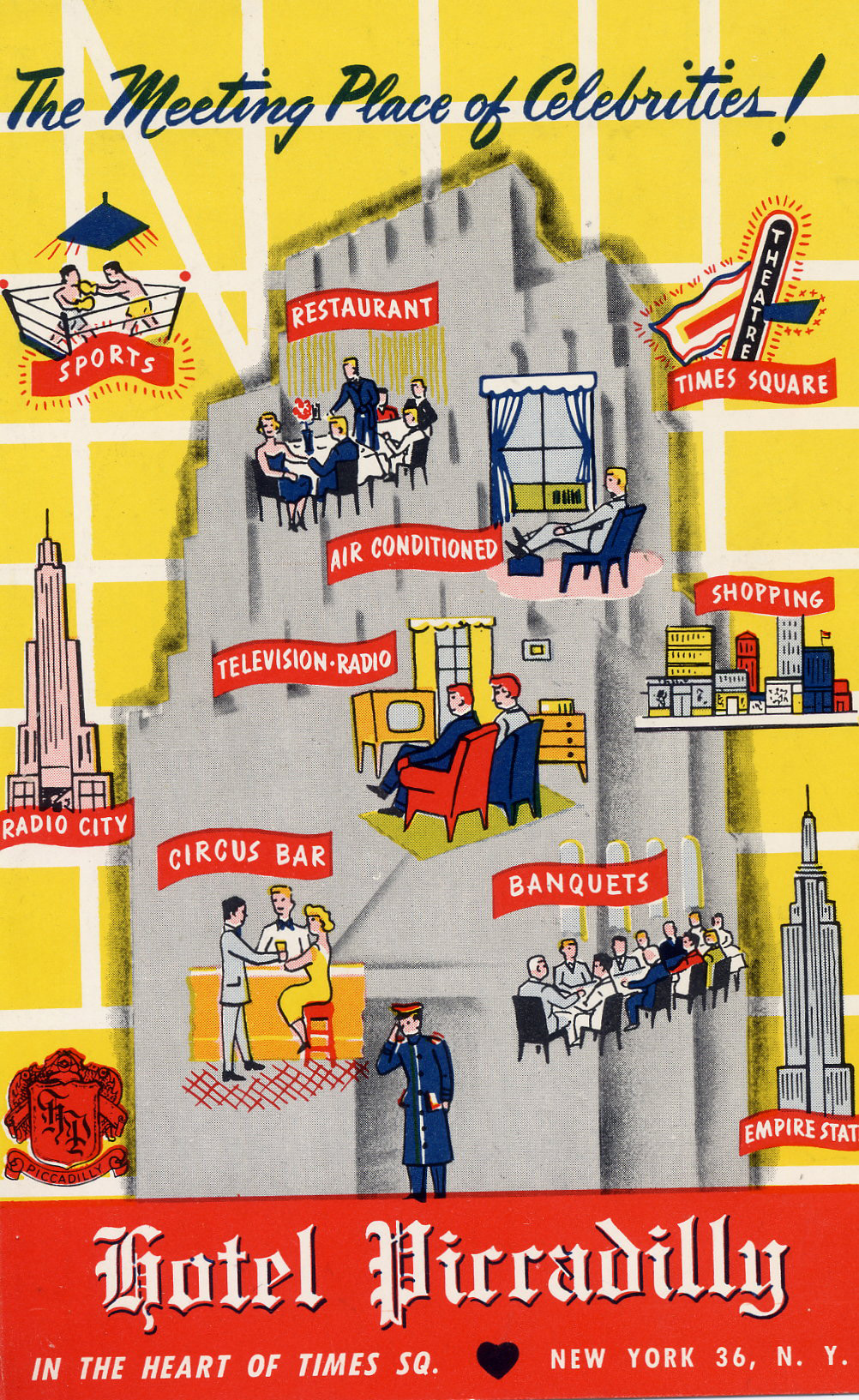

Now with air conditioning! And radio! And boxing!

Queen's Hotel, Montreal

Le Manoir, Riviere du Loup, Quebec

I can find very little interesting to say about either of these places.

The Queen's Hotel obviously is not the Queen Elizabeth Hotel in the same city, where John and Yoko took to their beds in 1969 and therefore set of a worldwide media frenzy for some reason.

It was once one of Montreal's best hotels, but in the way of hotels it fell on hard times before it was demolished in 1988. I learned that date via this loving reminiscence of a grandfather.

Which is what is really interesting about this exercise of post card-chasing. You plunge your hand in the muddy stream of the Internet toward some random object, and you come up with a fistful of mud and pebbles. You meet mundane family letters of obscure stage actresses who stayed at the hotel.

You also discover that there's an online button museum in which you can take a tour of the finest museums in the world, if by "tour" you mean a picture of their staff uniform buttons.

The Pennsylvania state capitol in Harrisburg is a pretty impressive pile of architecture. The old capitol burned down in 1897, and the new one was built (for the princely sum of $13 million) as a "palace of art." Pennsylvania had the good fortune to attempt this in one of the few periods in American history when that could be done with confidence, and without serious embarrassment.

Governor Pennypacker (one of my favorite Pa. governors and one of the few honest ones) deidated the building on Oct. 4, 1906, which means it just turned 100. The architectural inspiration was St. Peter's Basilica. The interior is adorned with Carrara marble, murals (by Violet Oakley and Edwin Austin Abbey), gold leaf, stained glass, and sculptures.

The most notable of the last are "Love and Labor, the Unbroken Law" and "The Burden of Life, the Broken Law" by George Grey Barnard, a disciple of Rodin.

President Theodore Roosevelt, among others, found them moving: "I recognize in the foreground two symbols which are supremely contrasted. One is humanity pausing, dominated by the influence of past error. The other is humanity advancing, inspired by the gospel of work and brotherhood," Roosevelt said.

Barnard's art, naturally, offended some folks since it included anatomically correct male nudes. But the Pennsylvanians didn't go as far school authorities at Kankakee (Ill.) Central School, Barnard's alma mater. Barnard caught them putting plaster shorts on the nude statues he had donated.

When he died, his friends said, "all America would remember him because ... he left a trail of beauty across the whole United States." But we've forgotten him. His will asked that he be buried in Harrisburg Cemetery so he could rest near the statues he considered his masterpiece.

The Connecticut state capitol building, erected in 1879, overlooks Hartford's 41-acre Bushnell Memorial Park. The capitol is less interesting than the park, from a historical point of view. Originally known as "City Park" (till it was renamed for the Rev. Horace Bushnell), the park dates to 1854, the first era of urban parks in America. City Park was the first park in the nation to be conceived, built and paid for by its citizens through popular votes. The great landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, a Hartford native, directed the layout of the park, which unfortunately was much impaired by a 1936 redesign after severe flooding.

The Corning Fountain, in the foreground, was erected in 1899 and presented by John Corning (of Corning Glass Works fame), "as a tribute to his father, a Hartford businessman who operated a grist mill on the site."

Designed by James Massey Rhind of New York, the sculpture uses a Native American theme, rather than a classical one, which would have been more typical of the period. The monument is made of marble and stone, 30 feet tall, with the figure of a stag (or "Hart" for Hartford) surrounded by Saukiog Indians, the city's first inhabitants.

If you've been following this series of old boring postcards, you'll know something about my father's family and family friends circa 1890-1940. They went to safe, sober places like Cleveland and Myrtle Beach and Ocean City and the World's Fair.

So how did this one slip into the collection? The caption on the back identifies the scene as Bombay, India! Exotic and decadent, with a swirl of curry in the fleshpots.

And guess what? The postcard, however it found its way into their album, is still boring!