GROUND ZERO

Luke and I visited New York today. I usually drive in, but driving's still being discouraged on Manhattan, so we took the train.

We could have gone right down to the World Trade Center site via the subway from Pennsylvania Station. But we popped aboveground and walked around the Madison Square Garden neighborhood first, because I wanted to get coffee and before heading to the disaster site I wanted to get a sense, for comparison, of how Midtown looked and felt (and, though I didn't realize it at the time, smelled).

I also wanted Luke to get a sense of skyscrapers. He hasn't been in the city since he was almost too young to remember it, and it takes a few minutes to adjust to the scale difference between Quarryville and 34th Street. I am raising a naturalist, of course, so the Empire State Building and the ways and markings of pigeons were equally impressive to him. I managed to dress us so we didn't look like obvious day-trippers, but the effect was spoiled by excited shouts of, "Dad, look, there's seven pigeons on top of that streetlamp!"

Back underground, we rode the A train 20 blocks down to Chambers Street, and surfaced about a block north of the no-entry zone around the World Trade Center. Right away, climbing out from the subway station to the sidewalk, you could feel the difference. Six weeks after the calamity, dust and ash still coats everything: a thin, gray film on the pavement and windows, piled in thick clumps on the awnings and ornamentals of buildings that hadn't been cleaned yet, including some blown-out storefronts. Some street-level offices stood empty, with just flag signs in the window and printed directions to the new, temporary home of the firm.

We walked out past the Woolworth Building and down Broadway, which is the western edge of the disaster site. Police barricades and chain-link fences blocked every cross-street -- Fulton, Dey, Courtlandt, Liberty. People stood up to them to peer in to the landscape of ruins.

Down each street, past the portable generators and emergency vehicles, through the reek of smoke and steam, we glimpsed slivers of what I've seen in hundreds of photo wire images. Each street seemed to focus on one or another icon of the nightmare: here wilted girders drooping from a broken foundation; here the black box of a ruined building, with banks of windows like dead men's mouths. The untouched skyscrapers were clean, hard-lined, glass-and-steel boxes. The wrecked buildings looked organic; like melted candles or rotting chunks of flesh.

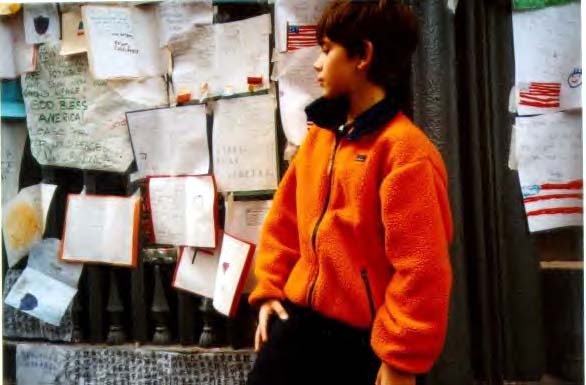

The fences that blocked the streets had bunches of flowers stuck in them, and flaglets and notes of sympathy or thanks or hope. Most of the handbills pleading for information about missing loved ones (which I had read about and seen pictures of) seem to be gone. Except for a few handbills and computer printouts of a bin Laden "Wanted Dead or Alive" poster I saw and heard very little of what felt like war fever or lust for revenge. There is less God blessing of America in Manhattan than out here in the provinces. People we walked with seemed only stunned, like they had come down to the site to connect the new reality to the old one. Their faces made me think of how an amputee would stare at the place where his lost hand had been.

There were many flags, from the billboard-sized one that covered the front of the Stock Exchange's pillars to the little hand-flags stuck in the garish pink porch awning of the Pussycat Club. The sidewalk and wrought-iron fence in front of St. Paul's chapel on Broadway was a mass of offerings and candles. This is the comfort station for the clean-up crews and rescue teams. A banner stretched the length of the fence, for people to write their names and messages of encouragement. It was covered in names, but Luke still found a place to squeeze his in, not far from those of country singer Charley Pride and what must have been half the state of North Dakota.

We made a right down Rector Street, the southern edge of the "Ground Zero" perimeter. Looking up Greenwich Street, which used to run right between the World Trade Center buildings, we finally saw Ground Zero: Two stories' worth of the latticework shell of one of the towers. Fragile, fused tuning forks. Like lace, like confectionery.

I told Luke, "You used to stand here and look up, up, up, into the clouds sometimes, and still not see the top." Every minute or two a flatbed would rumble down Greenwich Street with 30 or 40 feet of girder like a broken bone, burned and rusted, toward the barges parked at the foot of the island. What looks like limp pasta from a distance is steel so solid and huge it takes an 18-wheeler to carry just one of them.

Luke had brought two dozen cookies, molasses and chocolate chip, that he got, before we left that morning, from Simmons' Bakery in Strasburg. He said he was going to hand them out to police and firefighters. That gave our trip a purpose beyond rubbernecking, but I wasn't sure New York City cops would want to be pestered to take snacks from the hand of a 10-year-old. He handed out every one (well, we ate a couple on the way), and every man who accepted one was gracious and grateful. Only the U.S. military types at Ground Zero blew him off. The Manhattan personnel seemed genuinely impressed that a kid had come from Strasburg, Pennsylvania, to give them a cookie.

We walked halfway out the Brooklyn Bridge and looked back. I think if you had lived all your life in New York, that view would have meant something. But we hadn't. So much is crammed into that narrow tip of a small island. It was hard for us to sense an absence where there's still so much there; it's not like a missing tooth, with the obvious hole.

More shocking were the pictures everywhere of the skyline as it was when the towers still stood. People sold them on the sidewalks and they hung in the window of the bagel shop where we bought lunch. And you could look at the Woolworth Building, or One Liberty Plaza, or the World Financial Center, now tall trees in the forest, and then turn back to the photos from before Sept. 11 and see them as knee-high grass to the lost giants.

The smell. Pulverized, burnt concrete. If you've ever been to a house fire, it's like that, multiplied by 100 and then by two. It is a dead, wet, powder smell and it hangs all over the downtown. The day was brisk, with a steady northwest wind and speeding clouds, and someone said the stench was much abated from what it had been.

Oh, and we saw the mayor. We took lunch out to the front steps of Pace University, across from city hall, and afterward as we were drifting back toward Broadway, trying to decide where to go next, we saw a pack of media outside the mayor's mansion, and a few New Yorkers gathered on the sidewalk on the street-side of the fence. Then a couple of big, black SUV-type vehicles pulled in front of the house and someone said, "there he is." The man in a blue suit, with a cell phone pressed to his ear, walked up the steps and into the house without pausing to talk to the cameras.

The New Yorkers we stood with were half laughing at themselves for actually craning for a glimpse of this lame-duck politician (written off in August as a failure) in his newfound world celebrity. But like the ugly duckling towers, the meaning comes clear at the end.

(With apologies to William Faulkner):

For every American boy fourteen years old, not once but every time he can't quell it from rising in his mind, it's still not yet nine o'clock on that September morning in 2001, the planes have not yet taxied, the towers still stand in the golden dawn, and as the safe world awakens, heedless of the horror to come, fathers hurry to catch the train to their offices in the sky, briefcases in hand, kissing children, and it's all in the balance, it hasn't happened yet, it hasn't even begun yet, it not only hasn't begun yet but there is still time for it not to begin in those cockpits and time to avert the evil behind the blank eyes of Atta and Al-Shehhi and Hanjour as they walk purposefully through the airports saying nothing, yielding no clue of a life of hatred gathering to a head, yet it's going to begin, we all know that, we have come too far with too much at stake and that moment doesn't need even a fourteen-year-old boy to think: This time. Maybe this time, someone alert at the luggage check will notice something out of order, someone in the bowels of the FBI will fit the scattered clues together at the last minute, with all this much to lose and all this much to save: the Twin Towers, the Pentagon, the future, the lives of the brave and average men and women on the airliners about to rise ...

INDEX - AUTHOR