OUR GEORGE

It is substantially true that virtue or morality is a necessary spring of popular government. The rule, indeed, extends with more or less force to every species of free government. Who that is a sincere friend to it can look with indifference upon attempts to shake the foundation of the fabric?

Promote then, as an object of primary importance, institutions for the general diffusion of knowledge. In proportion as the structure of a government gives force to public opinion, it is essential that public opinion should be enlightened.

From Washington's Farewell Address. Go and read the whole thing on the man's birthday.

And remember, when the Founders talk about "virtue" and "morality," don't turn away with visions of James Dobson in your head. They meant something closer to self-sacrifice, compassion, public service, and high-minded patriotism -- good, sound human virtues that ought to resonate with any gender, sexuality, party, class, race, or creed. Gertrude Himmelfarb has ably defined the classical idea of "virtue" as "the will and capacity to put the public interest over the private."

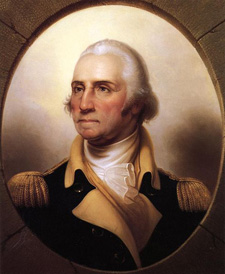

George Washington is beginning to recover his reputation; he deserves it. He was the steady hand on the tiller when we set sail as a nation. Steadiness, not reckless innovation, was the thing America needed at the time. It's to his credit that we forget the serpents of tyranny and mob rule that slithered about the American cradle. Read the history of the French Revolution.

The painter Benjamin West wrote that when he talked to King George III during the Revolutionary War, the monarch asked him what he thought George Washington would do if he prevailed.

Return to his farm, West predicted -- accurately, as it turned out.

"If he does that," King George remarked, "he will be the greatest man in the world."

George Washington's birthday should recover its original place in our national calendar. In the early 19th century, it was one of the two great national holidays -- along with the 4th of July. Memorial Day began with the Civil War, Veteran's Day and Labor Day are 20th century creations. Thanksgiving was a local New England custom and the German immigrants brought us Christmas. No right-thinking Enlightenment republican would have made a national holiday of Easter. But Washington's day was a great feast in the civic calendar.

Washington deserves his own birthday. I think Lincoln would agree. Here's one of the many stories Lincoln famously told to entertain his fellow lawyers on the long nights riding the circuit on the Illinois frontier:

One of the leaders of the American Revolution -- I forget now who it was, Ethan Allen, perhaps -- visited England after the war. His host entertained him comfortably, but was the sort of fellow who constantly disparaged America and Americans generally (no, it didn't start with George W. Bush) and never could get over the fact we had beaten them in the war.

To amuse himself and to twit his American guest, the host hung a print of George Washington in his outhouse. It had been there for a few days, and the host knew the American must have seen it, but he had said nothing. Finally overcome by curiosity, the host asked his guest what he thought of the picture of Washington.

"It is most appropriately hung," the American replied. "Nothing ever made the British shit like the sight of George Washington."

AMERICAN MYTH

Parson Weems and his biography of Washington loom large in the "Lies My Teacher Told Me" industry. Wretched literalists love to remind everyone who will listen that George Washington never chopped down a tree, never said "I cannot tell a lie," and never skipped a silver dollar across the Potomac. They claim these things are, or recently were, taught in schools as facts. They chew endlessly on the juiciness of a pious writer inventing a story -- a lie -- to illustrate the badness of lying.

Why did Parson Weems lie? I say he wasn't lying. I say he was inventing mythology.

We easily forget how new representative government was in Washington's day. The United States in 1787 became something that had not existed since before Christ, and the Founders harked back to ancient blueprints when they set up the American system.

They knew, for instance, that all the classical republics -- the ancient mixed government demi-democracies of Greece and Italy -- had hero-founder stories to bind them together. Athenian Theseus, Romulus in Rome, Lycurgus the lawgiver of Sparta. All the old republics built up public religions about supermen or demi-gods who taught the city-states how to live, how to grip the dangerous fire of freedom. Even the modern republics had such stories. William Tell is an example. Myth mattered; fact was irrelevant. Theseus's deeds in Athens were a pure fiction, and an astute Athenian who had read Homer certainly knew this.

Centuries later, Plutarch (himself something of a "parson:" he served as one of the two priests at the temple of Apollo at Delphi) looked out on the Roman Empire wracked by the tyranny of Nero and the bloodbath of civil war, and he sat down and wrote the "Parallel Lives." He knew his biographical information was unreliable. He had no intention of deciding what was true or of telling histories: he was setting up characters as lessons (or anti-models), to teach his readers about being citizens, being virtuous -- being human. Emerson called the "Lives" "a bible for heroes."

Parson Weems knew this new country of America also needed myths and hero-founders to bind it together in its diversity. His biographies of the founders are the American equivalent of Shakespeare's English history plays. Like Athens, we were a nation born myth-less. We were absent from the catalogue of ships, so Weems gave us a Mount Vernon Theseus to fill the bill. Like Rome, the United States (which still took a plural pronoun in those days) could not survive without common civic virtues. He gave us Washington as their exemplar.

George Washington, as a compendium of biographical details, hardly mattered to that purpose. And I believe Washington would have endorsed that. Which is exactly why George Washington ought to be put back on his birthday pedestal.

Washington is American history's grand exemplar of the virtue of civic duty. Say "actor-president" and people think Reagan, but Washington played a role so thoroughly, and so perfectly, that people still think he was that regal, noble Roman hero. When you read the accounts of him written by his intimate circle during the Revolution, you see the American man -- vain, hard-driving, hard-cussing, clever in a farmer's ways. And you appreciate what he did to get America launched on an even keel: passing up a life he could have spent happily among his horses, transforming himself into a living virtue as a gift to the new nation.

As the Revolution drew to a close, Washington deliberately reached back to yet another historical myth to ease the delicate transition from military revolution to civilian administration: Cincinnatus, the Roman hero who, during a crisis, reluctantly accepted the dictatorship for six months, defeated Rome's enemies in six weeks, then resigned and went back to his plow.

Now regarded as almost surely mythical, Cincinnatus was a real hero to the Founders. And when Washington resigned from public life in 1783 after the great victory and returned to Mount Vernon rather than mounting the throne of the new nation, he was the marvel of the world, and he was behaving quite deliberately on the classical model. His peers recognized it. Instead of becoming King of America, Washington became head of an association of Revolutionary War veterans -- the equivalent of today's American Legion or VFW -- called the Society of the Cincinnati. This was the classical idea of "virtue" as defined by Himmelfarb: "the will and capacity to put the public interest over the private."

As America's first president, Washington literally had to invent the job of being an elected leader of a nation, because there was no model for it in modern times. He had to parse out decisions about what title people should use when addressing the president, how a president should interact with Congress, how he should receive dinner invitations.

In some small details of protocol, Washington erred on the side of royalty. No harm done; Adams and Jefferson tilted the balance carefully the other way. The danger of having no dignity at the top, no noblesse oblige, was the greater danger, and Washington made sure we had enough noblesse to realize the oblige.

Washington stood for generations as a living example of American virtues, a monument in flesh before he became one in granite or marble. The nation chose him to bear the mantle of the American way, and he accepted the role.

Washington modeled himself on Cato the Younger. His favorite play was Joseph Addison's "Cato," which was based closely on the Cato section in Plutarch's "Lives." Washington ordered "Cato" performed at Valley Forge for the soldiers; he often quoted Cato (or his speeches from the play) at key moments. Historians who have studied his handling of the Newburgh mutiny of 1783, a key crisis in early American freedom, discovered it was directly lifted from Addison's play. [Act III, Scene 5, if you have a script; see Carl J. Richard, "The Founders and the Classics," pp.50-59].

The process that began in Washington's life snowballed upon his death in 1799. "America produced a flood of mourning pictures in many different genres: paintings, prints, sculptures, textiles, rings, ceramics. ... These images of George Washington became icons in every sense. They were reproduced in lithographs and chromos, hung on the walls of American homes, and regarded with a reverence that other people reserved for religious images." [David Hackett Fischer, "Liberty and Freedom," p.181]

Chief among the icons was a pamphlet, later expanded into a book: Mason Locke Weems's "Life and Memorable Actions of General George Washington," published a year after Washington's death. The Chesapeake clergyman and itinerant bible salesman wrote a lively, if overblown, prose, and told a series of stories meant to display Washington's "Great Virtues." It was one of many pamphlet biographies written mainly for the young, but it was the one that endured. And it set the general squarely in a classical context, consciously modeled on Plutarch.

Washington was as pious as Numa, just as Aristides, temperate as Apictetus, patriotic as Regulus. In giving public trusts, impartial as Severus; in victory, modest as Scipio -- prudent as Fabius, rapid as Marcellus, undaunted as Hannibal, as Cincinnatus disinterested, to liberty firm as Cato, and respectful of the law as Socrates.

Like the ancient Greeks, Weems' story turns history into mythology and mythology into history. Some of the stories were true, some were passed around as true in the oral culture, a few perhaps were entirely fabricated by Weems. All were embellished by him and hammered into morality tales to teach citizenship to young republicans. Virtue, not veracity, was the essential thing.

And so we get Washington barking the cherry tree, handling the school bullies, in the face of Braddock's defeat, refusing a duel, apologizing when wrong.

W itness, ye sons of tyrant's black womb,

A nd see his Excellence victorious come!

S erene, majestic, see he gains the field!

H is heart is tender, while his arms are steel'd.

I ntent on virtue, and his cause so fair,

N ow treats his captive with a parent's care!

G reatness of soul his ev'ry action shows,

T hus virtue from celestial bounty flows,

O ur GEORGE, by heaven destin'd to command,

N ow strikes the British yoke with prosp'rous hand.

That acrostic doggerel was signed only by "A Young Lady." One sees a carefully folded letter written in a small, fine hand, pressed on the editor of the Pennsylvania "Evening Post," who passed it back to the lead-blackened fingers of the typos and printed it in his columns on Jan. 7, 1777.

The "tender heart" that "treats his captive with a parent's care" is the core image. Young Lady probably was inspired by Washington's victories a few weeks earlier at Trenton and Princeton, whereafter the American rebels found themselves in possession of their first large crop of prisoners of war.

Washington made a point of ordering them treated well. That stood in contrast to the British and Hessians, who massacred wounded rebels and had tossed their prisoners from the New York battles of 1776 into squalid prison ship hulks in Brooklyn's Wallabout Bay. Some 12,000 died in the floating hells, their bodies rowed ashore daily for shallow burials. Walt Whitman, in his youth, would find their rotten bones and caved-in coffins amid the shifting sand of the Brooklyn shore.

Whitman, like most of his generation, absorbed the Revolution as a secular religion with Washington as its god. He would have understood Young Lady's mind, even if he eschewed her meter. He wrote of Washington as "one pure, upright character, living as a beacon in history." To him, Washington, before Lincoln arose, was the tender, loving father-figure. In one poem he has Washington kissing his generals on the cheek in tearful farewell -- an image about as likely, given Washington's steely nature and character, as the cherry-tree chopping incident.

In Whitman's intellectual ancestry is "Young Lady," upright at her desk, by candlelight, with a Philadelphia winter blowing outside, puzzling out the rhymes and believing, really believing, in the virtues of George Washington. Believing that they were what justified the revolution, and that those virtues, expressed at that moment, were being built into the edifice of a new nation.

The mythology still lived in 1860. Both sides in the Civil War claimed to uphold the true American values -- that is, the Revolutionary values. Not just their political rhetoric but the letters and diaries of soldiers. Leaving aside specific attacks on tyrants or traitors, it is impossible to tell North and South apart when they write positively about what they believe they are fighting for: "those institutions which were achieved for us by our glorious revolution ... in order that they may be perpetuated to whose who may come after" ... "the same principles which fired the hearts of our ancestors in the revolutionary struggle" ... "the perpetuity of Republican principles on this continent depends upon our success." Which was the soldier from Alabama, which from Connecticut, which from Tennessee?

James McPherson, working in the wake of the Vietnam War, explored the motivations of Civil War soldiers:

A veteran who became a student of the Civil War after his tour in Vietnam was awestruck by the dedication of soldiers in that earlier conflict. In all his Vietnam experience he had met only one American "who had the same 'belief structure' as the Civil War soldiers." In Vietnam "the soldier fought for his own survival, not a cause. The prevailing attitude was: do your time ... keep your head down, stay out of trouble, get out alive." How different was the willingness of Civil War soldiers to court death in a conflict whose casualty rate was several times greater than for American soldiers in Vietnam. "I find that kind of devotion ... mystifying." ["For Cause and Comrades," pp. 4-5]

Of course McPherson, and perhaps his unnamed student, had their own generational attitudes toward the war in Vietnam. But it seems the sea-change in American attitude was something that took place before Vietnam; World War II soldiers, who had cause to take up patriotic themes without embarrassment, tended to have no patience for such talk. The prevailing attitude wasn't the same as Vietnam, but perhaps was closer to it than it was to the Civil War: "Do your part, keep your head down, get home in one piece."

LOSING OUR RELIGION

There came a time, after the Civil War, after the centennial of the Revolution decade, after everyone with any living memory of it was dead, that thoughtful Americans could look ahead to a fuller, more mature contemplation of their history. By 1885 a majestic national historian like John B. McMaster, with a huge audience at his knee, could write about Washington the man, in ways more remarkable than the myth, and ready to step forth from behind the statuary:

No other face is so familiar to us. His name is written all over the map of our country. We have made of his birthday a national feast. The outlines of his biography are known to every school-boy in the land. Yet his true biography is still to be prepared. General Washington is known to us, and President Washington. But George Washington is an unknown man. When at last he is set before us in his habit as he lived, we shall read less of the cherry-tree and more of the man. Naught surely that is heroic will be omitted, but side by side with what is heroic will appear much that is commonplace. We shall behold the great commander repairing defeat with marvellous celerity, healing the dissentions of his officers, and calming the passions of his mutinous troops. But we shall also hear his oaths, and see him in those terrible outbursts of passion to which Mr. Jefferson has alluded, and one of which Mr. Lear has described. ... We shall know him as the cold and forbidding character with whom no fellow-man ever ventured to live on close and familiar terms. We shall respect and honor him for being, not the greatest of generals, not the wisest of statesmen, not the most saintly of his race, but a man with may human frailties and much common sense, who rose in the fullness of time to be the political deliverer of our country. ["History of the People of the United States," vol. II, pp.452-3]

And it is possible to look into the details of Washington's biography and see what might have been made of him for a modern America. Washington held himself aloof from his peers, as he felt befitted his role. He endured the familiarity of men who sought to treat him as an equal, but he never returned anything for it. Within the ordered social arrangements, he had few men who could be called friends. Yet one close companion was his able wife, Martha. She was in every sense his adviser and confidante. He married her though his heart was on another woman (Sally Fairfax). Stoic Washington never cost his nation a scandal. It would have been unthinkable.

Another who could be called a friend of the "cold and forbidding character" was his slave, William Lee, whom he bought in 1767. Washington called him not his "manservant," as was the custom, but "my fellow." Lee shared abilities in Washington's great first love: horses and riding. Lee was a brilliant rider and often the only man capable of keeping up with Washington in his fearless, breakneck pace on a northern Virginia hunt. Paintings showed them together in battle, and Washington emancipated him after the war.

Washington had slaves. Very well; every founder but Hamilton was touched by the taint of slavery. Yet Washington also managed the remarkable act of emancipating all his slaves and providing for them. There is a letter from him to Phillis Wheatley, considered the first important American black writer, thanking her for some verses, full of praise and courtesy and closing with an invitation to visit him.

He did not much care for immigrants, as a class, but he wrote of them, "If they are good workmen, they may be of Asia, Africa or Europe. They may be Mohammedans, Jews or Christians of any sect, or they may be atheists."

In all things, Washington was ahead of his time in that great modern value, tolerance.

But modern American intelligensia doesn't have Washington the complex man-hero, Washington the flawed and tolerant. Instead, we merely tore down the old myths, the old virtue-stories, and replaced them with -- nothing.

The 1920s was the decade America became modern. The New York musical, the historic preservation movement, Hollywood and the automobile all came of age. By 1929, five-sixths of the world's automobile production was in the U.S.; one car for every five people. Real per-capita income rose, millions of working people acquired savings accounts, life insurance, and their own homes for the first time.

Yet it also was the decade of Prohibition's nasty chaos, xenophobic Americanism and the second incarnation of the Klan. The Ten Commandments displays in courthouses and town halls, now subject of acrimonious lawsuits, often had been added deliberately in the post-World War I years to edifices that had stood for generations without anyone thinking they needed such stern brazen reminders.

Intellectuals veered left in the 1920s, but that was a consequence, not a cause. At heart they were not moving leftward so much as moving away from the traditional American narrative of values, which they felt had been discredited by the repressive hyper-patriotism of World War I and the vulgar middle-class prosperity of the '20s.

Edmund Wilson in the depths of the Great Depression celebrated the young intellectuals "who had grown up in the Big Business era and had always resented its barbarism, its crowding out of everything they cared about." For them, the Depression years "were not depressing but stimulating. One couldn't help being exhilarated at the sudden, unexpected collapse of the stupid gigantic fraud. It gave us a new sense of freedom; and it gave us a new sense of power."

Scott Fitzgerald put it bluntly in 1932: "The New Generation had matured to find all gods dead, all wars fought, all faiths in man shaken; all they knew was that America was going on the greatest, gaudiest spree in history." Another author, in a polemical book published the same year, summed it up like this: "Having surrendered idealism for the sake of prosperity, the 'practical men' bankrupted us on both of them."

Other intellectuals before had stepped outside the American mainstream and criticized it as narrowly violent, materialistic, crass, obsessed with false gods and rotten ideals -- Thoreau, Henry James. In the 1930s, this became a prevailing theme. Since then, it has only increased in fury. So much of the literary and academic class is fixated on American evil, to the degree of seeing nothing but it. Theirs is not the mature, whole vision foreseen by McMaster, but an infantile and poisonous replacement for Parson Weems.

They seem never to have advanced past the moment they learned Washington did not, in fact, skip a silver dollar across the Potomac. Somebody lied to them. Because the myths were not real, the virtues are not. America to them has been a perpetual disappointment. They pitched the whole project and set up a rival pantheon of "heroes" from some truly awful raw material -- from John Brown to Stalin to the Black Panthers. Would Che Guevara's life hold up as well as Washington's, if raked with the same historical scrutiny?

ANTI-MYTHOLOGY

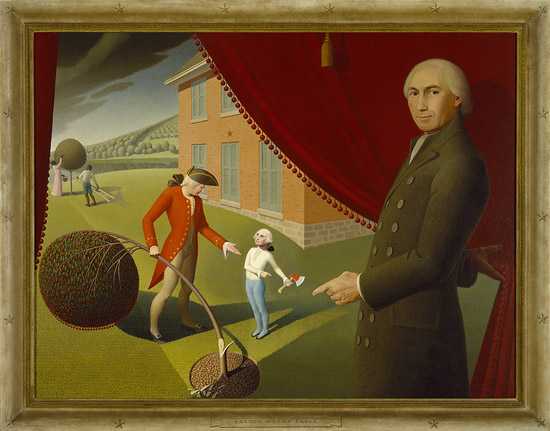

The "American scene" paintings of Grant Wood (1891—1942) are gentle satires. "Parson Weems' Fable" (1939, above) is based on Charles Willson Peale's portrait of himself lifting the curtain on his own museum in Philadelphia in which he sought to display and classify all the rich natural life of America. In Wood's painting, the parson lifts the curtain on a scene in which the cherries are as artificial as the curtain tassles. There are the slaves, too -- the embarrassing fact, in the background, and there is little George, with the head of old President George right off the 3-cent stamp. The picture is squared off and lit like a theater stage. Parson Weems's fable is a lie told to teach that lies are wrong. Wood enjoys this paradox and gently mocks it.

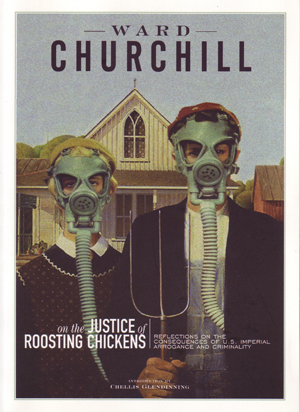

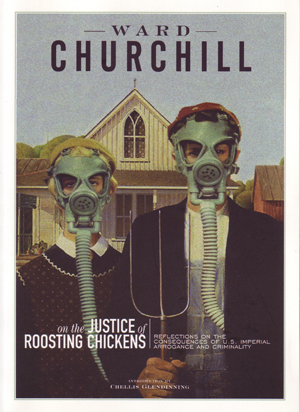

But much of the intellectual class in America has turned so hard and vicious in its contempt that it does not even recognize Wood's satire for what it is. Wood's paintings, such as "American Gothic," have been used as the basis of more brutal satire.

Such as here, on the cover of the book in which Ward Churchill's infamous essay is printed, comparing the Sept. 11 victims in the World Trade Center to Nazi Jew-killers. If Parson Weems missed the irony in telling a lie to teach the virtue of truth, Churchill, or his book designer, reveal their folly in tearing up a straw man of satire and thinking they are shooting arrows into the heart of Evil Amerikkka.

Washington's soldiers protected the captive Hessians from the Philadelphia mob in 1777. It also is true that the colonials in arms sometimes swapped barbarity for barbarity with their enemies, plundered and raped, and occasionally tortured and butchered POWs -- especially loyalists and runaway slaves who had joined the British.

The myth-maker's choice is which truth to place at the center of the story.

Weems was wiser than generally is recognized. In his version of the cherry tree story, according to Garry Wills ("Cincinnatus," p.53), the focus is on the father's wisdom in recognizing the courage of truth-telling. "It was in this way," Weems writes, "by interesting at once both his heart and head, that Mr. Washington conducted George with great ease and pleasure along the happy paths of virtue." It was a parable of parenting. Later retellings, especially in school readers, turned it into the advertisement for truth-telling that Wood satirized.

Washington was no idealist. He merged practical policy with the moral high ground whenever possible. In treating his Hessian prisoners well after Princeton, he had a strategic purpose. He wrote to the Pennsylvania authorities to whom he had sent the German POWs and directed them to "canton them in the German Counties."

If proper pains are taken to convince them, how preferable the situation of their Countrymen, the Inhabitants of those Counties is to theirs, I think they may be sent back in the Spring, so fraught with a love of Liberty[,] and property too, that they may create a disgust to the Service among the remainder of the foreign Troops and widen that Breach which is already opened between them and the British.

Canny! And as late as World War II, America still used such a policy on captured enemy POWs. What made Washington important is that he deliberately chose the virtuous path in the times when it didn't suit the immediate interest. His lesson by example was doing the right thing even when it went against expedience -- that cherry tree again.

We can smile now at the deliberate attempt by Weems and others to build an American mythology in parallel motion to republican Rome and ancient Greece. It seems a quaint excess, at best, to us. We find it superfulous to modern minds, modern democracies. We can excuse the Founders, and dispense with their fairy tales.

Or can we? Myths like those woven in 1800 by Parson Weems tell us who we are and what we stand for, and that tempers a great power by giving it a virtuous purpose. "Morality" has become a dirty word to a lot of people, because they concede morals to the prudes. So I'll go back to the word the Founders used: virtues. When Europeans carp about our patriotic religion and fixation with morality, I say, "you really don't want to have to deal with what we'd be without it." A great power without virtues is more deadly to itself and its neighbors than a great power that believes it has to live up to some high standard ordained by God, the gods, human experience, or history.

For generations, Washington's artificial example discouraged open displays of political ambition in America. Candidates were expected to be called to office, not to chase it. And if ultimately they developed a skill at furiously politicking while appearing to sit at ease on their porches and watch their crops grow, the model of Washington at least kept it from being too blatant. Only in Andrew Jackson's time did Americans realize what a powerful position they had created in their presidency, and the revelation shocked many men. The restraining model of Washington had, in large part, kept a check on baldfaced expression of power.

More important was the strong influence Washington's virtuous image held in the early republic among the officers of the Revolution, among the Southern aristocracy and Northern men of wealth -- the elite class that clustered in the Federalist and Whig parties. Histories of other lands show the fragility of young republics, and the temptation of just such classes to try to correct the excesses of democracy, and the wisdom of making it a point of pride among those classes to not intrude.

All this Washington accomplished, with the help of Parson Weems and the others who fed his mythology. Can a people live without myths? Can a nation survive without virtues? Aren't they the same question?

INDEX - AUTHOR