Two years ago, Gov. Roy Barnes redrew Georgia's state flag and stripped off the part of it that Georgia soldiers had carried in the Civil War. Last week, descendants of those soldiers sent Barnes packing.

Barnes lost his re-election bid to a Republican, Sonny Perdue. To put the Democrat's loss in perspective, consider that the last GOP governor in Georgia was a worthless carpetbagger who was run out of the state in 1871. Barnes had problems beyond the flag. But the electoral post-mortems, including Barnes' own, make it clear that the flag backlash helped Perdue leap the vote gap that usually divides the two parties in Georgia.

The new state flag is just plain ugly. It's as busy as a Denny's placemat menu. But that's not why a lot of Georgians hate it. They hate it because Barnes ramrodded the new flag through the state legislature in barely a week, with little debate. The Peach State was hosting or vying for five NCAA basketball events at the time, and the NCAA, under pressure from the NAACP, was threatening a boycott if the flag didn't change.

Barnes told legislators the popular anger would simmer down by election day. He was wrong. Everywhere Barnes went in the last two years, "flaggers" stood on the roadsides and highway overpasses, holding the old state flag. A hot-selling T-shirt showed the old flag and the inscription: "The Politicians can have their flag. This is my flag." Activists handed the general assembly a petition with 101,000 signatures asking that the flag be put to a vote.

As a former county GOP chairman in Georgia put it, "I tried for months to tell the Republicans down here that the flag was an issue, but they wouldn't believe it. I told them, "You don't understand -- these people won't whine and moan, they'll just go do something about it.' "

You don't have to be a race-baiter or a flag-waver to object to politicians making decisions that way. Arrogant I-know-better-than-you attitudes deserve to be voted out of office, whatever their political persuasion.

The Confederacy was about a great deal more than just the right to own other human beings as slaves. If the Rebel battle saltire represented nothing more than racism and hate, then I'd agree with the NAACP. But it's bogus history to say that it does. But having written and researched extensively on the battlefield business of that war, I've learned to appreciate the military effort and personal sacrifice put forth by the hundreds of thousands of Southern troops, more than three-quarters of whom had no direct connection to slavery whatsoever. Most of the historically minded people I talk to, North and South, whatever their feelings about CSA images used as political symbols, agree it is proper to place the South's flag on graves of men who fought under it. That's courtesy and honor to a soldier.

But this cannot be done in federal cemeteries, such as Point Lookout National Cemetery, in Maryland, where more than 3,000 Southern POWs lie buried -- victims of the North's version of Andersonville. The Parks Department's policy forbids their battle flag from flying there. The NAACP vows to push this further, and its leaders have stated their intention, "to commit their legal resources to the removal of the Confederate Flag from all public properties."

The fixation on modern American racism as some perverse peculiarity of Southern white culture allows Northern people to overlook a lot of deep problems, with discomforting solutions, closer to home. There is a racist subtext, if I may say so, in the statements I often hear up here, like, "We should have just let the South go."

Real integration doesn't mean putting the beggar on foot up on horseback and the beggar on horseback down on the ground to be whipped. The South now leads the North in things like real integration and power-sharing among ethnic groups in mixed communities. Compare Atlanta to Philadelphia or Baltimore. The balance now in place in so many places in the post-1970 South is the true legacy of the Civil Rights movement, but continued hounding of complex, harmless, beloved symbols like the old flag actually threatens to undo this legacy, not extend it.

The Southern whites who identified their heritage with that old Georgia flag can't be told to simply go back to Scotland where they came from. Not if you want the kind of America that Martin Luther King Jr. visualized. They have a place in it, too. And it's more than just crackers. Barnes lost big in the affluent Atlanta suburbs. And in Mississippi, which put its flag to a popular vote in 2001, in Hinds County (the majority black county that includes the city of Jackson), about a third of the voters chose the old flag.

The noise on this issue seems to come from non-Southern leadership in the NAACP. Running short of examples of institutional bigotry in the South, to put in its fund-raising appeals in the North, it turns to divisive attacks on symbols. Their anti-flag resolution is bombastic in the absurd: "WHEREAS, the tyrannical evil symbolized in the Confederate Battle Flag is an abhorrence to all Americans and decent people of this country, and indeed, the world and is an odious blight upon the universe," and so forth. To say that Southerners, black or white, are incapable of seeing through this hyperbole is, frankly, insulting.

Nov. 25

The backlash began at once. The "New Republic," to pick just one knee-jerker, fulminated against "a racially-tinged campaign promise," calling it "quasi-race-baiting" in one place and "good old-fashioned race-baiting" in another. Consistency be damned. Yet the magazine couldn't find anyone except themselves to call it "race-baiting," quasi-, old-fashioned, or otherwise. You'd think that at least Barnes, the humiliated candidate with nothing else to lose, would say so if he felt that way. But he doesn't.

"The morning after Perdue's stunning upset," the "New Republic" continued, "the national media started howling over the fact that the governor-elect had triumphed in part by exploiting the lingering resentment that many white, conservative, rural Georgians felt over Barnes's decision to overhaul the state flag."

Never mind the thumping majorities for Purdue in the affluent, educated counties around Atlanta -- including Barnes' own home county around Marietta. No, it just had to be all those toothless "Deliverance" types who are the only thing you'd ever see down in the South, yes it just had to be them, because every time we turn on the TV shows, gol durn it, there they are, grinning back at us.

And while I'm at it, here's the all-seeing "national media" (including the "New Republic") wobbling in the middle of the rink spotlight, trying to balance on its roller skates, a juicy target for a hip-check. Chomsky is right about the big media. It's not evil; it's lazy. Most Sunday nights I work the wire desk at my newspaper, and all the top national and international stories that flow in on AP, Reuters, Scripps-Howard, and the New York Times are based on what politicians said on the Sunday morning talk shows. That's not reporting. That's watching TV. Any idiot can sit on the couch with a channel-clicker. But that's how the big news organizations gather news. They leave real investigative work to crackpots with agendas, whom nobody believes even when they happen to get something right.

Where was the national media in the weeks and months leading up to the Georgia election? Was this some stealth thing? Or is it just possible that the "national media" don't have a clue what is going on in America outside the gated communities where their executives and their talking heads park their SUVs?

The "New Republic" article described the Sons of Confederate Veterans as "thousands of deeply nostalgic Southern-heritage warriors who like to stride about in their Confederate grays while fantasizing that Miss Scarlett is still perched out on the veranda anxiously waiting for Johnny to come marching home from the War of Northern Aggression."

I know a few of them. Good, decent fellows. You'd work along side them and never know it. This writer perhaps has them confused with re-enactors. Re-enactors are the ones who love to go dressing up. (They're actually a good-natured bunch, too; I did book-signings at some of their events). But then it's so much easier to convince people to despise cartoon characters than real human beings.

And then the "New Republic" quotes one of these neo-Confederate lunatics: "We know that he's got a big job to do in fixing the new government, and we're not trying to interfere with that."

See? See how crazy they are? And so those are the wild-eyed fanatics. That's the best the "New Republic" could do for scaring up a quote to prove the threat to civilization posed by these "offended crackers" who want to turn the hands of time back to 1861.

"... let's recall that the old battle emblem was not incorporated into Georgia's flag until 1956, specifically as a big screw-you to federally imposed integration."

Does it ever occur to these people to look at the Georgia state flag before 1956? From 1879 to 1956, the state flag was essentially the "Stars and Bars," the original national flag of the CSA government, with (after 1902) the Georgia seal off to one side. If you were going to link any state flag with slavery, that would be the one.

People who are going to write about the flag issue need to get a little education first. It doesn't take but 5 minutes to learn enough to write about the thing intelligently, whether you love it or hate it. People who care about the flags, not just the heat and the emotion, know that there's a terminology to them that allows them to be discussed accurately, and if you get it wrong, like the "New Republic" writer, you'll be regarded through the eyes of the tramps who stopped to watch Robert Frost splitting wood one spring day:

Men of the woods and lumberjacks,

The judged me by their appropriate tool.

Except as a fellow handled an ax

They had no way of knowing a fool.

The CSA Battle Flag -- the thing that's at the center of the state flags controversy in Georgia -- is technically not even a "cross" at all. In flag terms, a "cross" goes up and down, like the English flag. When the vertical shaft is shifted toward the staff, like Norway's flag, it's a Scandinavian Cross. A cross that runs full-length diagonally, point-to-point, like the Battle Flag, is a "saltire."

But there's a very old version of this (older than the flag terminology; it was used during the Crusades) called the "St. Andrew's Cross," which is a white saltire on a blue field. This is the flag of Scotland, and it is incorporated into the British Union flag (incorrectly called a "jack" by many Americans). It was deliberately mirrored in the CSA Battle Flag, since the heart of the white South was conscious of its Scottish heritage. But the colors were reversed, so it's not a true St. Andrew's Cross.

Here's a quick history of the Georgia flag's evolution out of the CSA flags. I promise this will be painless.

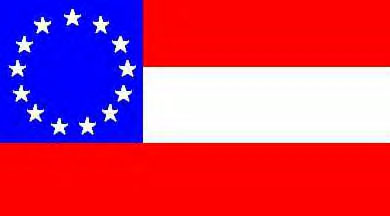

This is the "Stars and Bars," also known as the "First National." It was the original national flag of the CSA, and though the design changed later, including a brief period at the end of the war when the battle flag was added to the canton ("Third National;" few of them were ever issued), this is the most popular and recognized of the Southern national flags. The flag was deliberately modeled on the U.S. flag, as the South claimed to be upholding the true heritage and intent of the Founders. Some say the design was modeled as well on the Austrian flag (the designer was a Prussian).

The number of stars in the canton varied from 7 to 15 or more, as the number of states that joined the CSA grew, and depending on how the flag-makers chose to regard the slave states like Maryland and Kentucky that were more or less forced at gunpoint to remain in the Union.

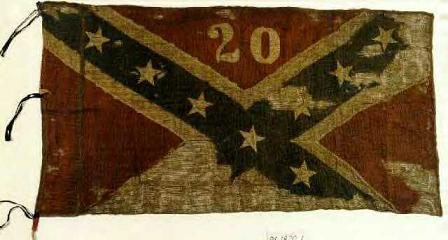

This is the "Battle Flag," the design carried by many of the Southern regiments (here the badly shot-up flag of the 20th Alabama Infantry). This pattern had been one of the suggested designs for the original CSA flag, but at the time the Confederacy had only seven states, so the seven stars created a symmetry problem that couldn't be solved, hence the design was rejected.

But the Stars and Bars turned out to look too much like the Stars and Stripes in battle, which could have deadly consequences, as flags were important rallying points and markers of troop positions on a battlefield. Confederate generals tried and failed to get the government to change its flag. In October 1861 they set out to create a purely military flag for the Rebel army in the East, and they found it in this design. By this time, the Confederacy consisted of 11 states and had recognized the delegation from Missouri, so 12 stars solved the symmetry problem. Unlike the regimental example above, the official army flag was square, rather than rectangular, for the practical purpose of being easier to make and saving material.

This is the official Georgia flag as it was after 1879. It was designed by a former Confederate officer and adopted at the end of Reconstruction. It deliberately mirrors the Stars and Bars.

After 1902, the state seal was added to the flag. The exact size and shape of the seal was tinkered with over the years. This is the version arrived at in 1920, which remained unchanged until 1956.

The 1956 flag, which replaced one CSA design element with another.

Most of the CSA leaders owned slaves. Most of the soldiers did not. By making the battle flag -- the flag of the soldiers, not the CSA government -- a central feature, Georgians can be said to have actually distanced themselves from the institution of slavery. But that was probably not their intention.

The Georgia legislators and governor in 1955-56, when the state flag was changed to include the Battle Flag, were rabid segregationists. They proposed some odious legislation, such as threatening to dissolve the state's public schools rather than integrate them. The resolutions on the 1956 Georgia flag change make no explicit mention of states' rights defiance and segregation, but it's safe to assume, as many do, that that was part of the underlying motive. Some defenders of the flag will claim that it was changed as part of the celebration of the centennial of the Civil War, but in Georgia's case, at least, the timing seems to rule out this motive.

Furthermore, the Battle Flag had been run up by the "Dixiecrats" at their convention in Birmingham in 1948. Both groups made their appeals to the people on the basis of states' rights and resisting federal control, and on the example of Reconstruction. In other words, even when they played the race card to white Southerners, they masked it.

But the Battle Flag's use as a modern symbol of defiance to the federal government goes back no further than that. For the previous 80-some years, it had been the veterans' flag, used almost exclusively at CSA commemorations. Frankly, the Dixiecrats got the wrong flag. The First National would have better suited their purpose. But they at least recognized what Johnston and Beauregard saw in the Battle Flag: it was a colorful and stirring cloth to rally around.

The 1956 Georgia Legislature, and the Dixiecrat convention, did not invent a symbol; they took one that had existed for decades, and gave it their purpose. Just like the Klan did when it marched under the Stars and Stripes. Some of my least favorite peoples -- John Ashcroft and Gale Norton f'rinstance -- agree with me about the Battle Flag. They would also defend the U.S. flag and the Constitution, seeing each of those things through their own filters. If I disagree with their filters it doesn't mean I disagree with the things they look at through them, and I am old enough to know that once in a while I'm going to find myself standing shoulder to shoulder with everyone I dislike, on some issue or another.

A whole lot of trouble could have been avoided if, in 1948 or 1956, the many Southern white people who felt a strong sense of regional heritage and historical pride had objected to this hijacking of their flag. If it had been kept as the soldiers' flag, and not the politicians', the case for keeping it today would be obvious. But the mistake was made; partly, I think, because the Dixiecrat pitch to the voters was put in terms of defending the state from Northern hegemony, rather than as pure race-baiting.

Here's the "money" line of the "New Republic" piece: "... just wait 'til Al Sharpton sets his sites on the return of Georgia's Southern Cross." [Sic -- should be "sights," -- but I'll overlook that except to note that the "New Republic's" copy editing is as fuzzy as its thinking.]

And so we think this is a good idea? We think Al Sharpton is the conscience of America? You want Al Sharpton riding into your town and telling you how things ought to be, what stays and what goes? Then why would you lick your lips as you wish it on someone else's town?

You'll end up living in a place like Madison County, Kentucky, where two high school students were suspended, twice, for wearing Hank Williams Jr. concert T-shirts that included the Battle Flag in their design.

If I would agree on banning the Battle Flag at any level, it would be on the bumpers and windows of Northern idiots who take it, again, and twist it to suit their personal psychodrama. Whenever I see it up here, I just think, "bad attitude." It's an insult to the flag for wanna-be Rebels with not an ounce of Southern blood, and not a scrap of dignity about anything, to be wrapping it around their license plates.

Having written a book about the Civil War (nothing political in it at all -- pure Bruce Catton-inspired storytelling) I've had a chance to spend some time with the devotees of that war, North and South, and I find the anger and pain over this issue, on the part of many good and intelligent people in the South, to be convincing. Again, if you want to see real integration in America, go to Southern cities like Atlanta, where the power structure has black and white leaders at all levels, and there's been no white-flight abandonment of the downtown. If you want to see meaningful integration, leave the North and go to states where the black population is 40 or 50 percent, not 4 or 5 percent.

American diversity is down there, and it's a legacy of the civil rights movement, which, in the South at least, ultimately realized that you can't just push all the "crackers" into a hole somewhere and put the lid on them. They're part of the landscape, too. And it only seems to be non-Southerners who want to upset the balance again by raising these phony "issues."

People who support the validity of the Confederate battle flag as a regional icon, and who are capable of articulating their reasons, often do so because the flag stands legitimately for the soldiers and common folk of the CSA, who were by anyone's measure a valiant and determined people embodying much of the best of America, North or South.

They may also see it as representing many of the qualities that the Southern soldiers fought for (as historians have determined them from contemporary writings), such as resistance to tyranny, regional distinctiveness, honor, and republican virtues. This approach sees the flag as a historic symbol, rooted in the Civil War experience of Southern people.

There are two main avenues of attack against this position, and they aim for the flanks. The first says any historical virtue that once represented itself in the flag was erased by the hijacking of that flag, circa 1948, by the opponents of integration and civil rights. Whose flag it was before that doesn't matter. What it stands for to too many living Americans, they will say, is the rearguard fight for institutional, state-sanctioned racism.

The other attack goes for the root and seeks to de-legitimatize the Southern experience of 1861-65. It presents the CSA as a rebellion by cabal of corrupt, immoral, cowardly, self-interested men, leading a deeply racist and slave-obsessed people whom it fooled long enough to get out of the Union and into uniform, and then kept there through coercion.

Two attacks, but usually the same attacker will subscribe to both of them. There is a cult of the Confederacy, in people who regard the CSA and its leading figures as some saint among nations, above history, outside time, touched by God, disconnected from the realities of all the other peoples, sections, and nations that have fought for independence. The anti-Confederate regards it exactly as they do. Except in photonegative. They see a magic kingdom in the clouds. He sees the bottom pit of Hell.

If you're a citizen of a Northern state and you disagree with me about what I've written, consider this:

There's an old-age home in the toney West End of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, the town where I live now (in the decidedly un-toney Seventh Ward). The plaque above the fireplace just inside the front door proclaims its origin and purpose: "The Henry C. Long Asylum, for the maintenance of respectable white women from the city and county of Lancaster and in indigent circumstances above the age of 45 years being widows and single women; to be admitted without any regard to their religious and political views."

It was established in 1905 by the same family that gave the town its big park. It wasn't until 1977 that the "asylum" was redefined as a home for older persons, white or black, male or female, of limited income. The current administrator told a newspaper reporter that the question of the plaque comes up at board meetings from time to time. "The thinking is that it's part of the history of this place," she said.

Would you feel differently about this if it was in Georgia, not Pennsylvania?