WILSONIANS

The Statue of Liberty has no wings; she is not an angel. The nation that reveres her often does things unwise or unjust. Like Athens, like Rome, like America. The motives of a great republic on the world stage are never pure; self-interest and idealism always find a balance, and the decision made and pursued usually is a matrix point that satisfies both.

But the balance between them is never perfect, and at times high idealism holds power in Washington. This "neo-con" administration seems to be such a time. History-minded Americans seeking a kindred age to ours could do worse than compare the current scene to Woodrow Wilson's administration and its aftermath -- World War I and the 1920s.

Under Wilson's presidency, as the war in Europe slowly drew America in, the idea of spreading freedom and democracy came more and more to the fore in America's foreign policy. George W. Bush is not a neo-con, and that group of thinkers forms just one part of the mix in his administration. But they have had the run of foreign policy for the past few years, so it is possible to speak of the administration in their terms, if foreign policy is the topic.

It's also been said that Bush's policies are "Wilsonian" -- motivated in large part by "idealistic" notions that America's blessings of liberty and democracy are the right of people everywhere, and our duty is to spread them and to roll back tyranny and repression.

But this is hardly unique; every American president since the start of the Cold War has been more or less a Wilsonian.

Bush and Wilson have been compared on a personal level: both deeply religious men whose background in American Southern culture colored their perceptions of social relations and power.

When Wilson turned from the president who won re-election because he "kept us out of war," to the leader who dispatched American leathernecks to the battlefields of Flanders, he used crusader rhetoric. So did George W. Bush, at first, before he backed away from it because it was toxic to Muslims. His abandonment of the word was the smart thing to do, but nonetheless it is the right word, because it embodies the notion of a war for a higher ideal than self-interest.

America's unique qualities made it uniquely suited to this job. As Wilson said, "Only free peoples can hold their purpose and their honour steady to a common end and prefer the interests of mankind to any narrow interest of their own."

CRUSADING

When America entered World War I, it contributed more than just the divisions of troops that tilted the balance on the Western Front. It infused an old European power struggle with an entirely new and world-transforming mission -- a crusade.

Wilson's war message to Congress described German unrestricted submarine warfare (the immediate cause of America's entry into the fight) as "a warfare against mankind." Wilson said "The wrongs against which we now array ourselves are no common wrongs; they cut to the very roots of human life."

He laid out a pre-emptive doctrine, in a situation where the practical realities of warfare had gotten ahead of the international laws and customs regarding hostilities. The international system was broken, because it had not been made to address such attacks as America was suffering.

Because submarines are in effect outlaws when used as the German submarines have been used against merchant shipping, it is impossible to defend ships against their attacks as the law of nations has assumed that merchantmen would defend themselves against privateers or cruisers, visible craft giving chase upon the open sea. It is common prudence in such circumstances, grim necessity indeed, to endeavour to destroy them before they have shown their own intention. They must be dealt with upon sight, if dealt with at all. The German Government denies the right of neutrals to use arms at all within the areas of the sea which it has proscribed, even in the defense of rights which no modern publicist has ever before questioned their right to defend. The intimation is conveyed that the armed guards which we have placed on our merchant ships will be treated as beyond the pale of law and subject to be dealt with as pirates would be.

This ought to sound familiar. After the al Qaida attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, many international legal experts -- even those not hysterically afraid of American power -- looked over the laws and treaties and decided that, while it was pretty clear that al Qaida, though stateless, would qualify as a belligerent power, it was not at all clear that the U.S. had any legal authority to take the only kind of military action that could crush it.

Another American president had found himself in a similar quandry; when South Carolina seceded in 1860, James Buchanan asked his attorney general, Jeremiah Black (an honest Pennsylvanian who later served Lincoln, too), to outline the constitutional position on the matter. Black concluded that, in effect, the secession was illegal, but the executive branch had been given no power to do anything about it.

Buchanan acted accordingly, scrupulously constitutional to the end. Lincoln followed him and in essence ignored the Constitution, forced the union to hold together, and let Congress write the necessary changes after the fact. No bonus points for guessing which leader is revered in history and which routinely makes the "five worst presidents" list.

Wilson's address also lays out a broader and grander purpose for America in this war: to spread freedom and democracy, and in effect to establish a new world order. America's object "is to vindicate the principles of peace and justice in the life of the world as against selfish and autocratic power and to set up amongst the really free and self-governed peoples of the world such a concert of purpose and of action as will henceforth ensure the observance of those principles."

In such a struggle, "where the peace of the world is involved and the freedom of its peoples," and where the threat to civilization comes from powerful autocrats not answerable to anyone but themselves, Wilson said, neutrality was impossible.

But even at its height, Wilsonian policy was not without self-interest. Instead, it merged idealism and self-interest. Spreading global democracy was in America's interest, because democratic nations are inclined to peace. They would be less likely to threaten America.

His call to arms reached a ringing conclusion:

We are now about to accept gage of battle with this natural foe to liberty and shall, if necessary, spend the whole force of the nation to check and nullify its pretensions and its power. We are glad, now that we see the facts with no veil of false pretence about them, to fight thus for the ultimate peace of the world and for the liberation of its peoples, the German peoples included: for the rights of nations great and small and the privilege of men everywhere to choose their way of life and of obedience. The world must be made safe for democracy. Its peace must be planted upon the tested foundations of political liberty. We have no selfish ends to serve. We desire no conquest, no dominion. We seek no indemnities for ourselves, no material compensation for the sacrifices we shall freely make. We are but one of the champions of the rights of mankind. We shall be satisfied when those rights have been made as secure as the faith and the freedom of nations can make them."

... It is a fearful thing to lead this great peaceful people into war, into the most terrible and disastrous of all wars, civilization itself seeming to be in the balance. But the right is more precious than peace, and we shall fight for the things which we have always carried nearest our hearts -- for democracy, for the right of those who submit to authority to have a voice in their own governments, for the rights and liberties of small nations, for a universal dominion of right by such a concert of free peoples as shall bring peace and safety to all nations and make the world itself at last free. To such a task we can dedicate our lives and our fortunes, everything that we are and everything that we have, with the pride of those who know that the day has come when America is privileged to spend her blood and her might for the principles that gave her birth and happiness and the peace which she has treasured. God helping her, she can do no other.

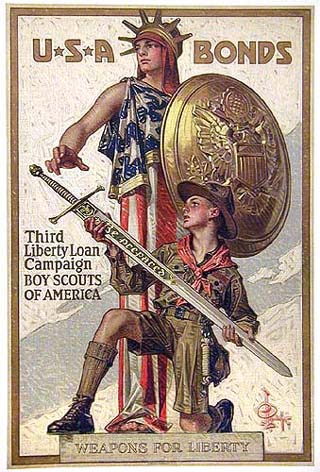

Lady Liberty grasps a sword. In peace, she's often painted as America's girl next door, a doe-eyed waif wrapped in a too-big flag. But in war, she flexes her Amazon muscle and towers to titan size.

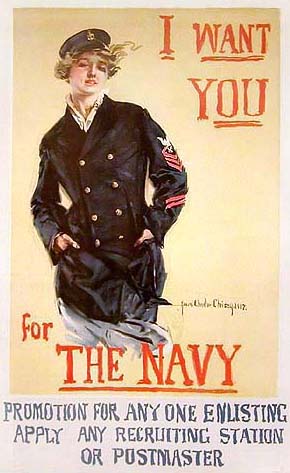

World War I produced some of the most dramatic and potent images in the history of American illustration. The Wilson Administration sought the cooperation of the nation's artists and advertisers, and by and large it got them to participate.

What crafted images will endure from the Iraq War? The creative voices of modern America seem to be solidly on the other side. Perhaps the most memorable propaganda production of this war will be Michael Moore's grim, pudgy face on his DVD covers. Neither for America nor for Iraq, but in the end only for himself.

To re-create the propaganda effort of 1917 probably is impossible today. Too much cynicism has flowed under the bridge. Propaganda, now in bad odor through association with the Nazis and the Soviets, was regarded as a positive thing in those days.

But if we are modern Wilsonians, we should learn from them. Surely more attention could be paid to the work of explaining our motives to the world, the Arab and Muslim world in particular. Surely, too, more could be done at home to connect this war with America's historical path.

World War I, like the Iraq War (to those of us who supported it) was a battle joined with lofty idealistic goals, but it was highly unpopular. The America that went to war against the Kaiser held a high percent of German-Americans, in the wake of the recent immigration wave. Cities like Cleveland were almost bilingual, with restaurants printing menus in both English and German. Milwaukee was 64 percent German in 1900, Hoboken 56 percent.

The socialist party also was at its peak of power and influence in America in those years. While the radical socialists opposed the war at once, the mainstream of the party, under the decent and honorable Eugene V. Debs, eventually joined them. Among other prominent opponents was Roger Baldwin, who would go on to lead the ACLU, which traces its roots to the American Union Against Militarism, formed by Baldwin and others in New York in 1914 to oppose American entry into World War I. Baldwin made his mark by founding a Bureau of Conscientious Objectors to oppose the draft.

Congressional opposition to Wilson's crusade was led by Henry Cabot Lodge. The president offered the grand vision of new world order and spreading democracy; the Congressional opposition held up nothing but stay-at-home spirit and narrow interest of a small class of wealthy and educated Americans.

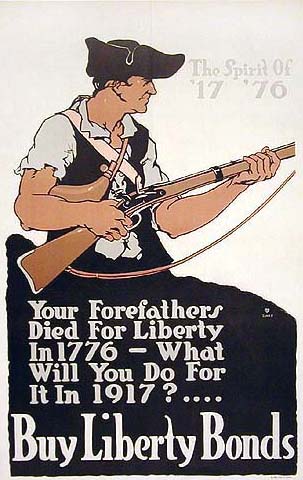

Liberty and freedom. The public mind craves images, and coherent narratives in times of crisis. Now the government concedes that to the anti-war opposition, and the artisans of the arts in contemporary America cobble together fables of "Fahrenheit 9/11." It was not always so. The patriotic propaganda of the Great War connected the great causes, and the public spirit of sacrifice for their sake, with America's past ...

... and with its most present fashions ...

... and even with great "crusaders" of history ...

Who happens to look, in this case, very "Hollywood."

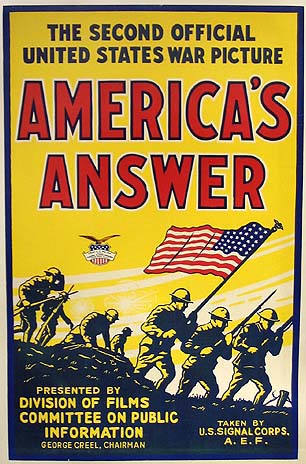

At the center of all this was the Committee on Public Information, which consisted of the secretaries of the armed services branches and George Creel, a progressive muckraker who had shone the light on child labor in 1914. "Creel combined the principles of Woodrow Wilson with the temperament of Teddy Roosevelt. Barely five feet seven inches tall, he boxed with professional prize fighters, married a prominent actress, played the lead role in a western movie, and vastly enjoyed the excitement of politics."

The four member "department" gives the wrong picture. The department was George Creel.

Creel hurled himself into the work with his prodigious energy. He hired Chicago promoter Donald Ryerson to organize a program of speakers to give four-minute speeches (many written by Creel himself) about American purposes in the war. Altogether seventy-five thousand "Four Minute Men" were carefully chosen (three letters of recommendation were required). They were trained by speech teachers and evaluated by a corps of inspectors. Creel, who had a passion for statistics, reported that they gave 755,190 speeches to 314,454,514 people in theaters, colleges, and clubs. There were Army FMMs on military bases and junior FMMs in schools. *

This war featured conscription, for the first time since the highly unpopular experiments with it in the Civil War. The question of "why we are fighting" thus touched many more people than it would with an all-volunteer army. The answer, from the FMMs, had to be clear and loud.

The war became a great crusade of American liberty, freedom, democracy, and civilization, against militarism, despotism, and barbarism. The American people were told they must join this great movement. Here was a new vision of America's role in world affairs, as the leader of a moral and spiritual movement to save other nations by converting them to liberty and freedom.

And that was just one of 18 divisions in Creel's department.

A Film Division produced movies in support of the war effort and generated a profit that supported other ventures. The Division of Civic and Educational Cooperation flooded the country with seventy-five million pamphlets. An Advertising Division distributed copy to newspapers. The Division of News issued a torrent of press releases. More than four thousand historians were recruited to check accuracy and to contribute their own work to the war effort. The Division of Syndicated Features distributed human-interest stories and opinion pieces about the war. Creel recruited the American artist Charles Dana Gibson to head the Division of Pictorial Publicity, which mass-produced an American iconography of liberty and freedom for the war effort.

Creel's work was not just for domestic consumption; it was aimed at world opinion. He made heavy use of radio -- or "wireless" as it then was called -- and managed to translate Wilson's speeches within hours of his delivering them, and broadcast them in languages around the world. Wilson's somewhat stilted and academic prose did not fit modern advertising techniques, and it was the committee's man in Russia who cabled Creel, asking for a statement of the president's war aims, "thousand words or less, short almost placard paragraphs," so "I can get it fed into Germany in great quantities in German translation, and can use Russian version potently in army and elsewhere."

Creel took this to the President, and pestered him till he submitted to the indignity of writing "slogans and advertising copy," and the result was the famous Fourteen Points.

Creel and his men took them and ran with them, shipped them into Germany, broadcast them from the Eiffel Tower, and "plastered them on billboards in every Allied and neutral country."

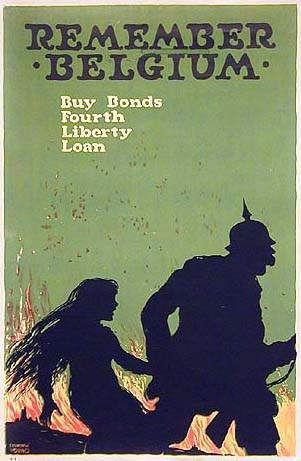

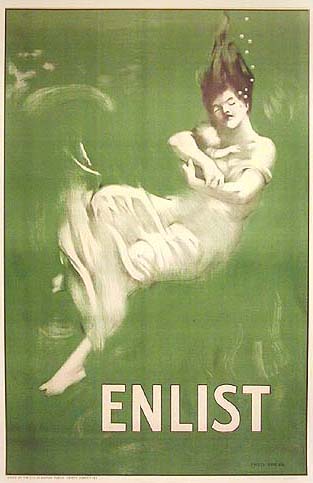

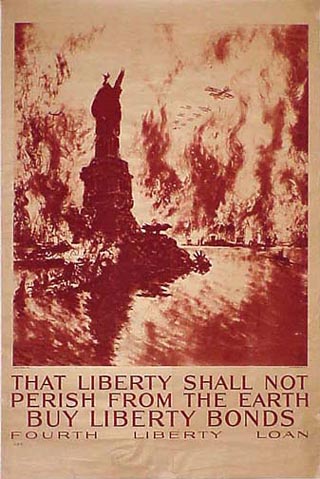

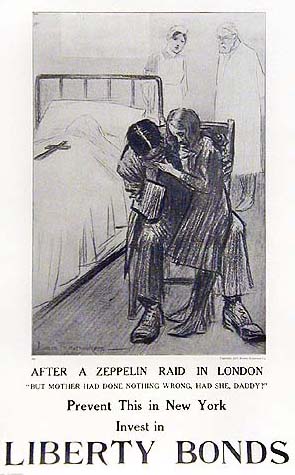

The posters and billborads, also reminded Americans, tirelessly, why they were fighting. Not just what they were fighting for -- Wilson's vision of a new, free world -- but what they were fighting against:

The rape of Belgium

An image from the sinking of the "Lusitania" in 1915. No need to explain the mother and child dead in the cold sea, or even name the ship anywhere on the poster. Every American in 1917 knew what this was.

A nightmare vision of the horror that might come. An air raid on America; New York in flames, the Statue of Liberty decapitated.

After a Zeppelin raid in London

"But mother had done nothing wrong, had she, daddy?"

Prevent this in New York

* [This thought is informed largely by my recent reading in David Hackett Fischer's "Liberty and Freedom." The chapters that cover World War I and the 1920s are among the most insightful in the book. The quotes, unless otherwise indicated, are from that source.]

Now tonight on the AP photo wire comes this image:

A U.S. soldier holds a dying child, its body torn by a "freedom fighter's" suicide car bomb in Mosul.

And some of our high-minded "anti-war" moralists have been pronouncing the killers of this child "the legitimate manifestation of a national liberation movement," acting in accord with the "ideals that are revered in the Declaration of Independence."

They say the insurgency must win. They say the Americans must lose. These progressives have thrown their favors to the champion they say represents the best hope for the world's future.

Their hero is not this anguished soldier, who, they say, should be defeated and killed if necessary. Nor does the child, the martyred innocent, represent their hopes.

The champions they admire are the soul-less thugs who slithered into Iraq, loaded a car with old artillery shells and drove it into a populated area and set it off to splatter bodies and kill mothers and babies.

And I wonder, where are the artists to scrawl the word "shame" over the face of such "progressives," as they once did over the murderers of the "Lusitania" or the ravishers of Belgium?

This mini-series ends with notes of warning, because Wilsonian idealism foundered on rocks of unintended consequences.

Wilson made his worst mistakes at Versailles. Germany had surrendered in expectation of a generous peace based on the Fourteen Points and later elaborations of them. But British and French leaders were hell-bent on revenge and on slashing the hamstrings of Germany's military power. America, too, in its thirst for reparations and passion for protectionist tariffs, turned the vise handle that squeezed Germany almost to starvation and empowered the revanchists.

Wilson made the mistake of going to Versailles personally, where politics and niggling details wrapped up his power. Had he stayed in Washington and let the diplomats do the drudgery, only intervening to resolve their impasses, he would have spent his political capital wisely. As it was, he became so distracted with the League of Nations project that he failed to insure that the peace it was built on gave it a firm foundation. His failure was a loss of the idealistic vision, not an excess of it.

Not only did it leave Germany betrayed, it created a host of new problems, and some of these were built into Wilson's idealistic vision. The map of Europe was peppered over with pockets of minorities, especially Germans and Hungarians. Large, polyglot empires like Austria-Hungary worked because they balanced the power arrangements among the many groups that comprised them. Versailles set all these peoples free and gave to each a nation. But no matter how carefully the lines were drawn, each ethnic nation ruled enclaves of another. And ethno-centric states were far less generous to their few minorities than bureaucratic mosaic-states like Austria-Hungary or Ottoman Turkey had been to their many.

Then Wilson suffered a series of debilitating strokes, and he left the country rudderless during crucial years. The Senate spurned his bid to bring America into the League of Nations. A compromise bill worked out by his old nemesis, Lodge, actually would have made for a more effective League, but Wilson, dying and bitter, ordered Senate Democrats to vote against it, and it failed.

CULTURE WARS

On the home front, in America, the First World War, as all wars are wont to do, galvanized forces already at work. Even before 1917, America was deeply worried about the drift of the United States, and the national identity itself. We've learned to talk in terms of "culture wars"and that's certainly what America was fighting among itself in Wilson's era.

Fear ran high that public morals were slipping, and that fear motivated a block of values-driven voters and inspired many political leaders. A political dynamic that evolved on Wilson's watch persisted throughout the 20th century, sometimes disguised by temporary alignments, sometimes starkly illuminated, perhaps never moreso than in the presidential election of 2004.

A rough description of it might be moral liberty and economic regulation vs. moral regulation and economic freedom. The political alignment that took shape was one that modern observers often trace back no further than Nixon's "Southern strategy." But Wilson would have recognized it. The strange bedfellows of the day were urban Democrats like Al Smith and silk-stocking Republicans like the Du Ponts. On the other side was an alliance of Evangelical Christians in all regions and Southern and Midwestern conservatives.

Prohibition was the flash-point issue in this war. Franklin D. Roosevelt's victory in 1932, which history texts tend to credit entirely to the Great Depression, had more to do with Prohibition than many people realize. Democratic posters that year showed Roosevelt and his vice presidential candidate in front of a full mug of beer. Among their campaign slogans was "Roosevelt and Repeal."

But the culture war was not just over booze; it encompassed recreational drugs, sexual licentiousness, prostitution. It is difficult to appreciate this today because it is difficult to recognize the old America, which tolerated a great deal that would shock us.

My current hometown of Lancaster, Pennsylvania, is in the heart of one of the "reddest" counties in the nation. Churches are huge; this is a last bastion of creationism in the Northeast, and even the Democratic candidates have to call themselves "conservatives" (they lose anyhow). A bookstore opened downtown 10 years ago with an "adult" theme. It was firebombed.

Hard to imagine now, but in 1913, this "city of churches" boasted 50 "beer clubs" and 72 saloons. The new pastor of wealthy, fashionable St. James Episcopal Church arrived and was astonished to find a house of prostitution flourishing on the same block as his church. On further investigation, he easily discovered 40 such houses of ill repute in the town. Saturday morning burlesque shows at the glamorous Fulton Opera House (which now features only symphonic orchestras and "family" musicals) featured nude scenes. Then there were the cockfights, the gambling and lewd entertainments at theaters, fairs, and carnivals.

The bawdy houses were integrated them into the local business community. A youth from those days whose reminiscences were published in the '50s, spoke of the whorehouses while reminiscing about his first jobs as a "long-legged, red-haired kid" working for a clothing store on Queen Street. "I remember delivering beautiful clothes on approval to an exclusive brothel that accepted only the best of clientele, situated on North Prince Street near Walnut. Tips for delivering there were never less than a dime."

Later, when he was 14, he worked for a stable, and became familiar with another house of ill-repute, run by "two girls."

"They were good-natured and jolly and full of fun. One was small and dark, and the other was big-boned and blonde. They would call to me over at the stable when they wanted me to run an errand. Often they invited the men from the livery stables over to the house to help drink up the beer left from the party the night before."

With public relations like that, it's no wonder that when the two women were hauled up on prostitution charges, the neighboring business owners all testified that they never knew of anything untoward going on there. "Well, the county paid the costs" of the case, he recalled. "Couldn't get anything on them, 'cause nobody would say anything against them. Fine girls!" What was unusual in this story was the charges being brought at all, since the brothels were widely tolerated.

Modern-day "South Park Republicans" probably would be Hemingway Republicans back then. "He hated Fascism with a passion, despised liberalism and conservatism, wrote with respect of some Communists but disliked Communism. To John Dos Passos he wrote, 'I suppose I am an anarchist -- but it takes a while to figure it out. ... I don't believe and can't believe in too much government--no matter what good is the end. To hell with the Church when it becomes a State, and the hell with the State when it becomes a Church.' "

But this, too, was the era when the modern "liberal/left" in America first emerged -- the intellectuals and academics and the mainstream media (personified in Mencken) rose up to lead the reaction against fundamentalism and political excesses in the name of patriotism. At the same time, they ran up against the uncomfortable fact that America's most persistent pathologies are rooted in the essential stuff of America: the individualism, the sensible morality, the Protestant ethic, the commitment to ideals.

How could they attack the excess without seeming to aim at damaging the American ethic itself? How could they disown essential American qualities without turning the Land of the Free and the Home of the Brave into a lobotomized Europe Lite? Dewey began to sketch the frame of this problem as early as 1922 (in "The American Intellectual Frontier"). But his peers didn't solve that problem in the 1920s. They still haven't.

REPRESSION and ANXIETY

American politics are a wide field, and the lines runs far left and far right. But there is an out-of-bounds. When your passion for some position takes you past respect for the basic fabric of the system we live under, freedom and justice for all, the rule of law and democratic institutions, when you advocate anarchy or dictatorship or repression, then you've ceased to be part of America.

In the years after World War I, fear of foreign-born terrorism led to domestic programs and policies that undercut the Bill of Rights.

Collective righteousness, which Wilsonian war politics encouraged, can easily become ungovernable and cruel. Wilson had had premonitions of this; he spoke of it in 1916, when he was still the peace candidate: "Once lead this people into war and they'll forget there ever was such a thing as tolerance. ... The spirit of ruthless brutality will enter into every fibre of our national life."

Wilson was a progressive Democrat. The tendency of progressive Democrats to favor its ideal version of reality at the expense of messy free expression and basic rights is familiar to anyone who follows the PC wars on modern university campuses. But runaway righteousness is a broader problem than that; it is the trap of crusaders.

George Creel at first took the high road in his Committee on Public Information work during World War I. He rallied the nation with positive images of America's best qualities. The artwork he commissioned focused on the enemy as militarism and autocracy, and on its victims. The German people, as Wilson made explicit in his war message to Congress, were not the enemy. Like many Americans, Creel had German ancestry.

But eventually he stooped to lurid attacks on the Kaiser, German-Americans, dissenters, and the opposition press.

He even turned on Congress itself. Congress responded by cutting off his funding stream, which quickly caused his department to collapse. Creel had crossed the line.

Others followed. Intolerance and xenophobia during World War I were far worse than the supposed horrors of the McCarthy era. The Espionage Act (1917) and the Sedition Act (1918) put the screws to the Bill of Rights. The Sedition Act punished expressions of opinion, regardless of their likely consequences, which were "disloyal, profane, scurrilous or abusive" of the American form of government, the flag or the military. Under it, "Americans were prosecuted for criticizing the Red Cross, the YMCA and even the budget" [Johnson, "Modern Times," p.204].

Wilson, while he was still governing, had the opportunity to curb these abuses, but he did not. After he was incapacitated by strokes, the zealots ran wild, and the witch-hunts culminated in the notorious Palmer raids.

There are lessons in this for modern-day Wilsonians. For one, history shows that, so far from being a new Nazi Germany (as Bush-haters insist), America today is not even as repressive as it was in 1920. The civil rights violations of the Palmer raids were far more serious than anything done or proposed in the name of the Patriot Act. (And at the same time they were far less serious than those of Lincoln's Administration in 1862 or the repression of the loyalist elements in the Revolution.)

But history teaches us that that way lies the danger.

Though it may have been fuel on the fire, I can see no direct connection between the idealism of Wilson's world-changing course and the repressions that grew under his administration. Rather, the repression sprang from pre-existing domestic fears following an era of heavy immigration and a vague awareness of a foreign menace in the form of "bolshevism."

If anything, the idealism of the president's rhetoric lent itself to the defense of rights. The Wilsonian idealism was a magic mirror held up to the authorities when they pursued repressive policies at home. Walter Lippmann wrote in a private letter in July 1920, "It is forever incredible that an administration announcing the most spacious ideals in our history should have done more to endanger fundamental American liberties than any group of men for a hundred years." Many agreed, and said so in public.

And rights advanced dramatically in America in that decade, for workers and for women. It's an open discussion among historians, whether those advances came more from the efforts of those who embraced the national crusade in World War I than those who rejected it. I tend to come down on the side of the ones who took the idealism and made it their own.

Another lesson in all this is that ham-handed prosecutions eventually recoil in great advances in civil rights. Ever since the Zenger trial in 1735, American civil right have emerged stronger from every attempt to quash them. The authorities may bully, and they may have the strong arm, but eventually the case goes to court, and there the rights win the day.

As long as eloquence can come to their aid, personal liberties will triumph. The outcome of a particular case is no matter. In the 1920s, John Scopes lost his "monkey" trial in Tennessee. But the trial itself turned the hearts of Americans. Our love of liberty triumphs, in a Hollywood ending, over our yearning for order and the fear of the strange.

Provided the courts get to hear the case. Be vigilant of rights, 21st century Wilsonians; one of the tendencies in a highly moral regime is to interpret other systems of morality as enemies. And to see legal appeals as an impediment to progress.

And those foolish enough to wish to legislate our morality would do well to remember the lesson of Prohibition; the impossible dream that put a bad taste in the American mouth to the whole idea of "legislating morality."

INDEX - AUTHOR