CAVE MAN

Early archaeologists and anthropologists regarded the Stone Age cave paintings in Altamira or Lascaux (great web design on the latter site, by the way) as certainly frauds.

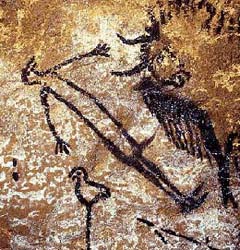

It's not just that the images are so strikingly modern they can be transfered, virtually intact, into modern-day advertisement art:

It's that -- well, look at them! Nobody picks up a charcoal stick for the first time and draws like that. This is the result of a long process of art skill-acquisition. Perhaps spread over generations. If we have a half dozen of these cave scenes, they imply hundreds, or thousands, of designs in bark, pottery, tattooing, that have been long lost.

It's that -- well, look at them! Nobody picks up a charcoal stick for the first time and draws like that. This is the result of a long process of art skill-acquisition. Perhaps spread over generations. If we have a half dozen of these cave scenes, they imply hundreds, or thousands, of designs in bark, pottery, tattooing, that have been long lost.

This all had to be supported by the surrounding culture. Someone had to feed that guy (or girl) off the communal kill while they learned the art of drawing and painting. Someone had to take time away from gathering wild roots to go collect and grind the materials needed to mix the pigments. It's such a leap from the notion of the late Ice Age savages clinging by their nails to the fringes of survival.

Why? The answer usually given, I suppose, is "magic." That is, this art was crucial to the religious beliefs of the artist's people, to the superstitious attempt to bring about a successful hunt or to reinforce the cycle of birth among the hunted animals.

And yet ... It's too much. Religion contents itself with a recognizable outline of the thing in question. Christians don't try to make the crucifix they carry look as authentically tree-like as possible. In fact, religions tend to prefer abstraction and symbols to pure representational art. Modern religions periodically cast out religious art when it gets too representational or too good (Council of Trent, iconoclasts), as the detailing and the egoism of talent interfere with seeing the god-stuff in it.

Look at the image at the top of this post, from Lascaux. The human is a glorified stick-figure, albeit posed skillfully, so you almost intuitively sense he's dead. But the bison is different. Somebody not only drew bison, he took care to draw it so well -- not graphically real in the Norman Rockwell sense so much as true to the moods and motions of an animal -- that it instantly appeals to the eye of Picasso.

"Divinely superfluous beauty" is the poet Robinson Jeffers' phrase, and he thought that the evidence of God was in that the creator took the trouble to limn the deep interior surfaces of sealed seashells with luminous substances. From what but sheer joy in being the creator? Here, in Lascaux, I think it is a human trait -- "humanely superfluous beauty." Here was an artist. Not because he drew a bison for the people's ritual: Because he drew it better than it needed to be.

And yet ... After the Stone Age came the Neolithic. When in almost every place representational art disappeared. Geometric designs took its place. They are frankly boring. Lines, angles, zig-zags, across the entire surface of pottery, over and over; whole museums of them that speak nothing to us.

Our representational art is a rediscovery, or a re-learning. We are not direct heirs of Altamira. This stuff might as well have been done by space aliens.

INDEX - AUTHOR